The First Darwin Hospital

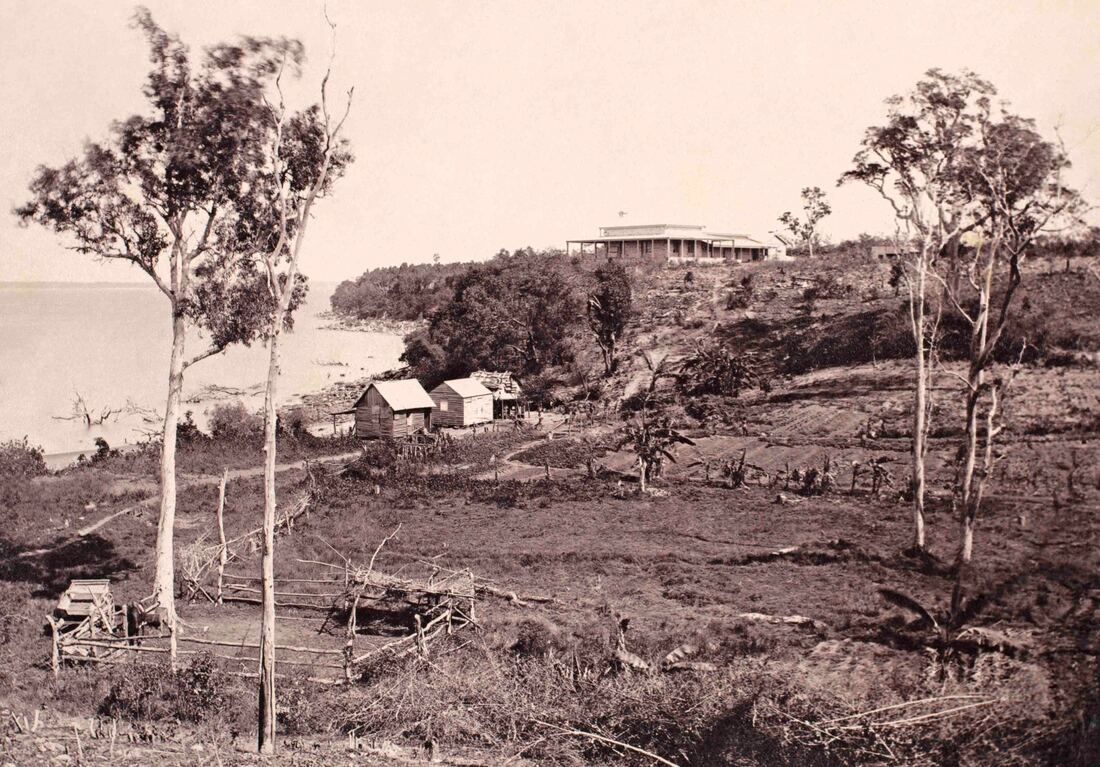

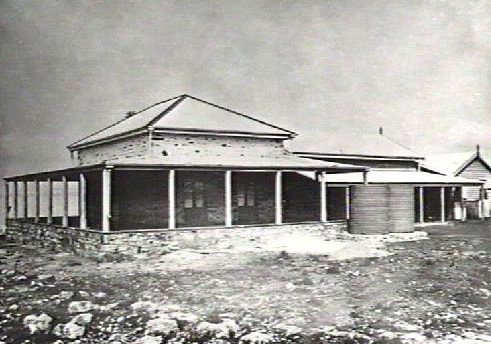

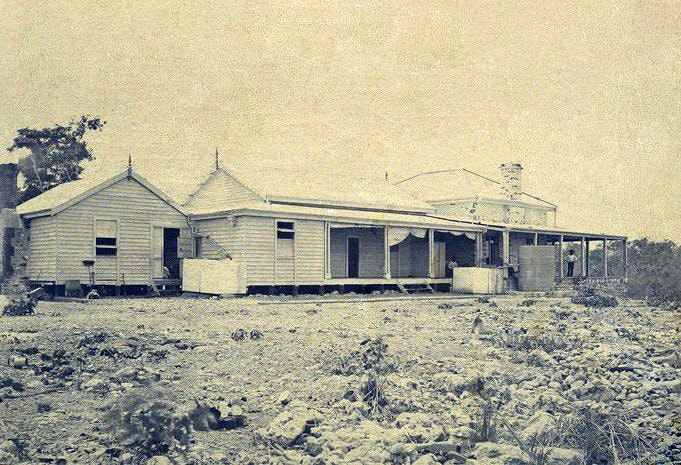

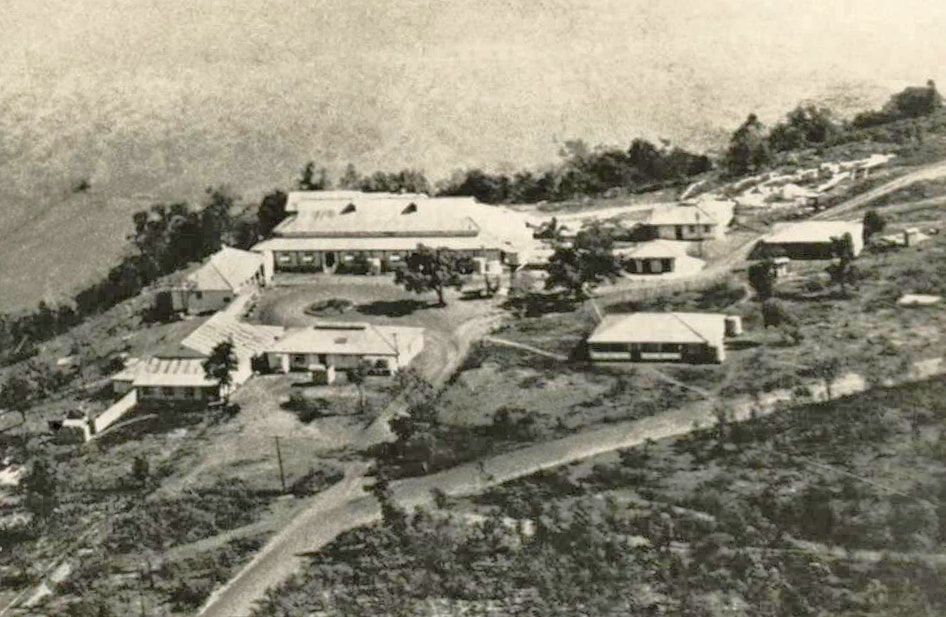

The first hospital for Palmerston on Port Darwin was built of timber in 1874 and much appreciated by the white ants. It was built on Packard Street overlooking Doctors Gully under the authority of Dr James Millner. By 1878, the hospital was improved with stone. During the next 40 years, the hospital was administered by South Australia. In 1911, the Commonwealth Government assumed control. Construction of an 89-bed hospital fronting Lambell Terrace commenced in 1941 to cater for the Darwin area population of 4,000. The new hospital opened 2 February 1942 and was bombed just 17 days later during the Bombing of Darwin.

“The building of the Overseas Telegraph Line made world history. During the inland construction gold was found and when this message reached the world there was a gold rush. Men arrived in every available ship and headed inland ·following the telegraph line and the wheel marks of the survey drays. Many of these men, and those walking overland from Queensland around the

Gul£ of Carpentaria, brought with them malaria and dysentery. In their haste to find gold men ignored all basic hygiene practices.

During the wet season water lay in the many holes that had been dug and mosquitoes abounded. Those who did not die of malaria or dysentery had their health undermined by a diet of white flour and white rice. The deficiency disease beri-beri took a heavy toll but the disease was not understood. Hundreds of men died but thousands more came to replace them. Terrible stories of human suffering reached Adelaide over the telegraph line and a very generous woman, recorded only as Miss da Costa, gave £100 to build a ward of a hospital; when this was completed she gave more for a second ward and other buildings so the poor men would have somewhere to go when ill. However, those men had first to reach hospital and unless they had a mate with a horse and dray they still died in the bush.

Dr. James Stokes Millner was the first doctor appointed to the new settlement and he was loved by all. Even the Aborigines realized this kind man could help them. Over the years ahead the response of the Aboriginal people to a health service reflected the attitude of respective doctors towards them. The doctor was officially the Protector of Aborigines but successive Government Residents forbade them to leave Palmerston, so the role was largely a farce. In 1875 Dr. Millner and his family took a holiday and sailed to the east coast of Australia in the "Gothenburg". This ship sank off the coast near Gladstone on 24 February 1875 and all lives were lost.

In the meantime the hospital was opened with Matron Alice McGuire, a British nurse and her husband as the only staff. Aborigines were engaged to carry water from the well in Doctor's Gully and to do other work, but these people had first to be taught. The nursing was heavy and the stay in hospital long as there was no other accommodation for seriously debilitated men.

The miners decided the Northern Territory was not suitable for Europeans and asked for Chinese coolie labour. The first two hundred Chinese were recruited from Singapore; they were all men and there were no medical examinations as long as no smallpox or plague had occurred in the ship. The European miners treated the Chinese badly and in a short time the Chinese were looking after their own interests by panning through tailings from the mines. News spread and over 3000 Chinese came in the next few years through Hong Kong. These people were poor but industrious; they started market gardens in and around Darwin, one such garden in Doctor's Gully. Others started gardens wherever there was arable land and sold vegetables to the white miners. Some of their countrymen caught fish, dried them and traded them inland. Chinese business men came and brought their wives. In a short time . it became obvious that many Chinese were doing nicely and ugly jealousies arose where there were not enough police to control men who tended to be a law unto themselves.

Both white and Chinese men who were without wives soon sought out Aboriginal women. Massive social problems followed, not the least of which was the introduction of leprosy. The Chinese were jailed for trafficking in opium and gin and it was in the jail that the doctors diagnosed both leprosy and tuberculosis. Aborigines jailed along with the Chinese contracted tuberculosis and many inmates of all races died from beri-beri. Dr. Percy Moore Wood protested about the insanitary conditions in the jail and also over the beginnings of a slum in Cavenagh Street but Government Resident Parsons forbade him to write such things.

In 1882 Mrs. Manson was the Matron of the hospital and her husband was the medical assistant. Mr. Manson died of pulmonary tuberculosis. It was about this time that Professor Robert Koch in Germany isolated the tubercle bacillus. Until then no one knew tuberculosis was so infectious.A small ward for female patients was built in 1886. Prior to that the occasional woman was nursed in the Matron's cottage. A second nurse and a second medical assistant were appointed. There was no midwifery in the hospital until 1911 when the first maternity ward was added. Prior to that midwives came by ship from Adelaide at great expense for the few who could afford such luxury. A doctor could deliver a baby at home and charge a special fee.

Gul£ of Carpentaria, brought with them malaria and dysentery. In their haste to find gold men ignored all basic hygiene practices.

During the wet season water lay in the many holes that had been dug and mosquitoes abounded. Those who did not die of malaria or dysentery had their health undermined by a diet of white flour and white rice. The deficiency disease beri-beri took a heavy toll but the disease was not understood. Hundreds of men died but thousands more came to replace them. Terrible stories of human suffering reached Adelaide over the telegraph line and a very generous woman, recorded only as Miss da Costa, gave £100 to build a ward of a hospital; when this was completed she gave more for a second ward and other buildings so the poor men would have somewhere to go when ill. However, those men had first to reach hospital and unless they had a mate with a horse and dray they still died in the bush.

Dr. James Stokes Millner was the first doctor appointed to the new settlement and he was loved by all. Even the Aborigines realized this kind man could help them. Over the years ahead the response of the Aboriginal people to a health service reflected the attitude of respective doctors towards them. The doctor was officially the Protector of Aborigines but successive Government Residents forbade them to leave Palmerston, so the role was largely a farce. In 1875 Dr. Millner and his family took a holiday and sailed to the east coast of Australia in the "Gothenburg". This ship sank off the coast near Gladstone on 24 February 1875 and all lives were lost.

In the meantime the hospital was opened with Matron Alice McGuire, a British nurse and her husband as the only staff. Aborigines were engaged to carry water from the well in Doctor's Gully and to do other work, but these people had first to be taught. The nursing was heavy and the stay in hospital long as there was no other accommodation for seriously debilitated men.

The miners decided the Northern Territory was not suitable for Europeans and asked for Chinese coolie labour. The first two hundred Chinese were recruited from Singapore; they were all men and there were no medical examinations as long as no smallpox or plague had occurred in the ship. The European miners treated the Chinese badly and in a short time the Chinese were looking after their own interests by panning through tailings from the mines. News spread and over 3000 Chinese came in the next few years through Hong Kong. These people were poor but industrious; they started market gardens in and around Darwin, one such garden in Doctor's Gully. Others started gardens wherever there was arable land and sold vegetables to the white miners. Some of their countrymen caught fish, dried them and traded them inland. Chinese business men came and brought their wives. In a short time . it became obvious that many Chinese were doing nicely and ugly jealousies arose where there were not enough police to control men who tended to be a law unto themselves.

Both white and Chinese men who were without wives soon sought out Aboriginal women. Massive social problems followed, not the least of which was the introduction of leprosy. The Chinese were jailed for trafficking in opium and gin and it was in the jail that the doctors diagnosed both leprosy and tuberculosis. Aborigines jailed along with the Chinese contracted tuberculosis and many inmates of all races died from beri-beri. Dr. Percy Moore Wood protested about the insanitary conditions in the jail and also over the beginnings of a slum in Cavenagh Street but Government Resident Parsons forbade him to write such things.

In 1882 Mrs. Manson was the Matron of the hospital and her husband was the medical assistant. Mr. Manson died of pulmonary tuberculosis. It was about this time that Professor Robert Koch in Germany isolated the tubercle bacillus. Until then no one knew tuberculosis was so infectious.A small ward for female patients was built in 1886. Prior to that the occasional woman was nursed in the Matron's cottage. A second nurse and a second medical assistant were appointed. There was no midwifery in the hospital until 1911 when the first maternity ward was added. Prior to that midwives came by ship from Adelaide at great expense for the few who could afford such luxury. A doctor could deliver a baby at home and charge a special fee.

The first Chinese diagnosed with leprosy were deported but once ship's Captains became aware of this they refused to take these men. In 1889 an isolation hut was built at Mud Island directly across the harbour from Port Darwin. This became a holding centre for leprosy for the next forty years. The

victims, Aborigines and Chinese; were given food and water; chaulmoogra oil was the only medication and it in fact cured nothing. In 1931 Channel Island quarantine station became the leprosy hospital for the next 24 years.

To assist the inland miners and open up the country, a narrow-gauge railway line was constructed as far as Pine Creek between 1885-89. A hospital of a sort was built at Burundie and then shifted to Pine Creek. It was a thankless task for a doctor; he could advise men on the prevention of malaria and dysentery but most men didn't want advice. During Dr. Gilruth's time as Administrator, 1912-20 the railway was extended to the north bank of Katherine River and in 1926-31 it was constructed as far as Birdum and there it ended. Indian labourers were brought in and possibly introduced more diseases.

Darwin is prone to cyclones. The hospital was seriously damaged in 1897 and Dr. F. Goldsmith commended Matron Maria Davoran and Nurse Birkett for the manner in which they coped. Less damage occurred during the 1937 cyclone. By 1900 there were three nursing staff and two male medical assistants.

Dr. C.L. Strangman introduced the first microscope to Darwin in 1908. Earlier doctors had been refused this expensive luxury. This made diagnosis more scientific but even so there were infections such as Donovanosis that had him baffled. Some patients spent months in hospital. The hospital was most inadequate but it had three metre wide verandahs and during the dry season patient slept on these.

victims, Aborigines and Chinese; were given food and water; chaulmoogra oil was the only medication and it in fact cured nothing. In 1931 Channel Island quarantine station became the leprosy hospital for the next 24 years.

To assist the inland miners and open up the country, a narrow-gauge railway line was constructed as far as Pine Creek between 1885-89. A hospital of a sort was built at Burundie and then shifted to Pine Creek. It was a thankless task for a doctor; he could advise men on the prevention of malaria and dysentery but most men didn't want advice. During Dr. Gilruth's time as Administrator, 1912-20 the railway was extended to the north bank of Katherine River and in 1926-31 it was constructed as far as Birdum and there it ended. Indian labourers were brought in and possibly introduced more diseases.

Darwin is prone to cyclones. The hospital was seriously damaged in 1897 and Dr. F. Goldsmith commended Matron Maria Davoran and Nurse Birkett for the manner in which they coped. Less damage occurred during the 1937 cyclone. By 1900 there were three nursing staff and two male medical assistants.

Dr. C.L. Strangman introduced the first microscope to Darwin in 1908. Earlier doctors had been refused this expensive luxury. This made diagnosis more scientific but even so there were infections such as Donovanosis that had him baffled. Some patients spent months in hospital. The hospital was most inadequate but it had three metre wide verandahs and during the dry season patient slept on these.

In 1909 Dr. Strangman was permitted a trip by ship along the Arnhem Land coast to Borroloola and return. This was the only medical visit to check the health of Aborigines during the forty years of administration by South Australia. This visit was to prepare the way for new policies for Aborigines under the Commonwealth Government which took responsibility for the Northern Territory 1 January 1911.

The Commonwealth Government had big plans for development. The hospital was expanded and the first maternity ward was built. However, there was no reticulated water, everyone still relied on rain-water tanks, wells or bores. Two doctors were appointed to Aboriginal health surveys, and one of these, Dr. Mervyn Holmes became Chief Medical Officer and did a great deal to improve sanitation in the town. Dr. Holmes left many valuable reports; he also wrote a handbook on health for people in the outback and introduced medical kits on church missions, cattle stations and outback police stations. He prepared and introduced sound health legislation relevant to the tropics. At this time there were five trained nurses in the hospital.

The Administrator, Dr. J.A. Gilruth, a veterinary surgeon, had the go-ahead to develop experimental farms and to introduce good quality cattle and horses for breeding. The Vestey's Company, with large cattle properties was invited to build an abattoir on the site occupied by Darwin High School near the Museum. Hundreds of men came in as labourers and brought with them radical ideas. Communism was new and sweeping the world and strikes were the order of the day. As venereal diseases and alcohol were a considerable problem a compound was established for the Aborigines at Kahlin in 1912. Also the railway was extended and the men in camps demanded medical care but would not implement acceptable standards of hygiene or obey advice on the control of malaria.

World War broke out in Europe (1914-1918} and when finance was severely cut the unionists became even more aggressive. Malaria, dysentery and gonorrhoea were the biggest and most time consuming health problems. It can be said the Unions brought disaster; the abattoir only operated a couple of years and was then closed for ever. Poverty struck and the hospital had the role of caring for the destitute and many aging men from an earlier era.

In 1916 Dr. Holmes went to the War. He was replaced by Dr. Leighton Jones, who did his best but the situation was more than he could handle. The hospital became very run down and Matron Ethel Lang, a sweet but ineffective personality, was accused of letting the hospital be overrun by cats and poultry. At the time of Dr. Cecil Cook's arrival in 1927 the nursing staff had just resigned as a body in protest at the Matron's mismanagement. Dr. Cook accepted all the resignations but then began to realise a mistake had been made. Sister Constance Stone reconsidered and became the first Infant Health Sister in Darwin. Sister Olive Mansbridge stayed on as Matron until more staff could be recruited and Matron Lang's contract was not renewed.

Dr. Cecil Cook was young and arrogant and although he did much good work he also caused much strife. Matron Ida Ashburner took over in 1928 and continued at the hospital until her marriage in 1940. Dr. Cook introduced legislation for a Nurses Registration Board, Medical Board and the registration of dentists. Nurse training was introduced in 1929 using the syllabus for nurses in Queensland, an arrangement that continued until May 1964 when the training was changed to the New South Wales syllabus and examinations. There were six trained nurses and three doctors in Darwin, one of the doctors being Dr. Cecil Cook, the Chief Medical Officer. There was no mention of the purchase of any teaching aids and the hospital itself was old and primitive. Local girls were encouraged to train and the first to complete the course was Beatrice May Rogers in 1933. She went to Perth to do midwifery, married and did not return. By 1940 there were nine trainee nurses but as all records, including the Register disappeared during the war it is uncertain how many had completed training before 1942.

A new quarantine station was built on the mainland in 1929 and Channel Island was occupied as a leprosy hospital in 1931. Dr. Cook insisted that the leprosarium be staffed by a married couple, the wife being a trained nurse. In this he differed from the Government but he insisted and succeeded.

The patients from Mud Island and a group of mixed-race women who were at Darwin Hospital moved to Channel Island in August 1931, about 40 people in all. A few months later patients started to arrive from Western Australia and continued to do so until Western Australia built a hospital at Derby in 1940.

In 1935 hospitals were developed at Katherine and Tennant Creek. In 1939 the first Government hospital was opened at Alice Springs to replace the small hospital run by the Australian Inland Mission. March 1934 saw the arrival of Dr. Clyde Fenton with his own aircraft. He started an Aerial Medical Service from Katherine and was paid six pence per mile for his aeroplane. Dr. Fenton loved adventure and took many hair-raising risks in rescuing sick people. There was no radio so he flew without it. He told people in the outback that if they cleared airstrips he would land in an emergency and he did. Once when blown off course he ran out of fuel and landed beside a billabong; it took searching aircraft many days to find him. After three crashes he could not afford another aeroplane.

In 1937 the Government bought an aeroplane having realised the life-saving value of this service. In May 1940, just as he was achieving some facilities at Katherine, he joined the R.A.A.F. Another pilot flew the aircraft and it crashed at Katherine in October 1940. An unconscious Sister Dorothy Black was rescued but the patient perished when the fuel burst into flame.

A financial recession known as the Great Depression struck Australia in the early 1930s and everyone took a cut in salary. Many were out of work and destitute people were once again looked after by the hospital. Dr. Cook introduced a Medical Benefits Fund and although he was directed not to coerce people, there is no doubt that he did so. He controlled the Fund himself and claimed it was a success but by 1939 it was heavily in debt and the scheme was placed in the hands of the Taxation Department to collect the money and pay the hospitals.

By the mid-1930s war became a real threat and Darwin began to develop as a military outpost. The civilian airstrip was on the site of Ross Smith Avenue and it was too small for the R.A.A.F. who in 1938 surveyed the present airport. The R.A.A.F. base was still being constructed when bombed in 1942. Army numbers increased and as they had no barracks they used Vestey's meatworks. Darwin was without reticulated water for the many thousands of men in the area until the pumps at the new Manton Dam were started on 10 March 1941. Prior to that the army put a small weir across Howard Springs and pumped water from there this facility still remains.

Darwin Hospital was soon grossly inadequate in both space and equipment. Plans were drawn up for a new hospital but experts who visited from Canberra decided that Canberra had a more urgent need for a hospital than Darwin. The hospital design allowed for two infectious wards and in 1938 Dr. Cook had these built on the Kahlin Compound site to isolate and treat venereal diseases. A new settlement for the Aborigines was built at Bagot and as they moved on to this site in 1939 the Army took over Kahlin Compound for a tent hospital. At that time dengue fever was a considerable problem and as men were away from home they had to be nursed in hospital. Even the doctors developed dengue fever.

On 3 September 1939 war started in Europe but men in the armed services recognized a threat nearer home as the Japanese were arming and being aggressive. In December the heads of the three services in Darwin, Army, R.A.A.F. and Navy, jointly signed a letter to the Minister for the Army demanding a new hospital in Darwin. Parliament approved the funds in June 1940 and work commenced on the Kahlin Compound site about January 1941. All building supplies were delayed by militant wharf laborers and this continued after Japan entered the war.

As the old Darwin Hospital could not cope the Army took over Bagot Aboriginal settlement where there were buildings and developed 119 A.G.H. there with a staff of forty Sisters and about one hundred orderlies. The Aborigines were sent across the harbour to Delissaville. Most of 119 A.G.H. was canvas and the site was not suitable but the need was urgent. The R.A.A.F. built its own small hospital with a doctor and six Sisters while the Navy planned to use a wing of the new Darwin Hospital when it was completed.

Sister Edith McQuade White, who had been with the Northern Territory hospitals since 1936, joined the army and became the matron of 119 A.G.H. Later, in mid-1942 she was the Principal Matron in charge of A.A.N.S. in the Northern Territory. When she went to New Guinea late in 1943 she was replaced by Matron Susan Haines.

The Army built a new hospital at Berrimah (Kormilda College site) and moved the medical section there on 1 January 1942 long before the buildings were completed. Japan attacked Pearl Harbour on 8 December 1941. Orders were given for women and children to be evacuated from Darwin. Most went out by ship as there was no highway while others who could afford to pay went by Catalina flying boat. It was a distressing time as many people had no family connections in the south. Darwin, being frontline, was placed under strict censorship and the newspaper printed no local news.

Nursing staff and a few other women in key work such as the Post Office were permitted to stay. By January 1942 there were thousands of Americans in Darwin pending further orders. The equipment, X-ray included, did not arrive for the new Darwin Hospital but the need was desperate and the hospital was occupied on 2 February 1942. The Army loaned a mobile X-ray unit and the Americans loaned 150 beautiful quality beds. A few months later the Americans needed the beds and Darwin Hospital was issued with low folding army beds.

The hospital ship “Manunda” came into Darwin Harbour on 16 January pending further orders. At 10 a.m. on 19 February 1942 the aircraft from the same four aircraft carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbour mercilessly attacked Darwin. Three American aircraft hit back but were outnumbered. No Australian aircraft got off the ground.

There were five functional hospitals in Darwin and all received damage. In spite of the red crosses on the roof eight bombs fell in the vicinity of Darwin Hospital; two outside Ward 1. wrecked the end of the ward. The R.A.A.F. hospital was destroyed but all the staff were in slit trenches and survived.

Berrimah (119 A.G.H.) was deliberately strafed by aircraft and one man, too sick to be moved to a slit trench. was killed.

Bagot (119 A.G.H. surgical) was caught in the hail of bullets fired at an American aircraft trying to get aloft - the pilot bailed out and was brought in as a patient next day. The X-ray unit at Bagot was put out of action by a bullet. "Manunda” in the harbour was deliberately attacked twice. A bomb went through the skylight of the music room and exploded at C. Deck, killing twelve. Two others died a couple of days later. Sister Margaret De Mestre was mortally wounded and Sister Lorraine Blow was dangerously wounded. Their dentist was killed outright. After the all clear siren sounded Army ambulances took the wounded to Bagot and Berrimah while civilians in town found their way to Darwin Hospital. In spite of four internal fires ''Manunda" continued to function and admitted over seventy patients direct from the ships sunk in the harbour. Lifeboats from "Manunda“ worked overtime and two of the crew were wounded in the boats when strafed by the enemy.

A Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service had not been established in Darwin and there were no intravenous fluids or blood transfusions given as the equipment was not adequate. The first Soluvac saline and glucose became available in July 1942. Lieutenant-Commander Sam Sewell (R.A.N.) brought in a Julien Smith direct transfusion set ten days later and then if a man was wounded during an air raid a mate with the same blood group was to accompany him to hospital this worked well for both civilians and servicemen.

On 20 February, the day after the bombing, Surgeon-Commander Clive James authorised the evacuation in "Manunda" of all the wounded from Darwin. He did not have this authority and was dismissed from the Navy a few days later. Most of the wounded were too ill to be moved but once the action of loading the ship had started it had to continue. The wharf had been destroyed so patients were taken by lifeboats and the lifeboats were then lifted to the required deck for transfer. The ship’s lift was out of action. "Manunda" sailed that night, looking like a porcupine with dunnage poking out of seventy holes in the hull. Matron Claire Schumach specialled Sister Blow whose condition was dangerous; this left 14 Sisters and about 100 orderlies to care for 260 other casualties. Major Keith Bowden was the only surgeon in the ship - "Manunda" was not meant to carry front line battle casualties. The laundry was out of action and much of the ships fresh water had been lost due to perforated water lines and fighting fires within the ship. Fifteen patients, most of whom had suffered extensive burns, died in the ship on the way to Fremantle.

Back in Darwin the police and the Army hygiene teams counted and buried the dead. When the deaths in "Manunda" are included, over 300 lives were lost. The Post Office staff were all killed when struck by a bomb, while most of the other casualties were from among the wharf laborers and the crews of sunken ships. The original Darwin Hospital became the living quarters for the hundreds of sailors stranded without ships.

Darwin Hospital was taken over by the Army and Dr. Bruce Kirkland, the Chief Medical Officer joined the Army in June and became Commanding Officer in 129 A.G.H; (Darwin Hospital). The civilian nursing staff were sent south and the hospital was without women again until December 1942. The Army hospitals (Bagot and Berrimah) were moved inland to Adelaide River where conditions were very primitive for many months. An Army hospital (121 A.G.H.) was established at Katherine while Tennant Creek and Alice Springs were also taken over.

The leprosarium on Channel Island was not bombed but Matron Elsie Jones was ill and she went south on the train five days after the bombing. When she reached Tennant Creek she left the convoy to stay with friends at Rockhampton Downs, 112 kilometres from Tennant Creek. On 10 March she became acutely ill and Dr. W. Straede and his wife went out by car to rescue her. The Straede's car broke down and both perished from thirst in that hot dry country. The next day Elsie Jones was flown out by the Flying Doctor Service from Cloncurry; she died in Brisbane Hospital on 17 May 1942. Elsie Jones, as Sister King, had been the first Sister at Victoria River Downs during a devastating

outbreak of malaria in 1922; she had travelled there by horse and buggy.

For the first two years of the war the Army hospitals were immensely busy. Over Christmas 1942 to New Year 1943 both Adelaide River and Katherine Hospitals peaked at over 900 inpatients. Many were refugee women and children from Indonesia, and most had dysentery or malaria or both. An ambulance train, comprising converted cattle trucks, moved the patients down the line to make room for more that train was bombed while at Adelaide River and a medical orderly was killed·. The Americans brought in their own hospitals to look after their airmen; their largest hospital was at Nightcliff.

In April 1943 the first two Catholic Nursing Sisters arrived to restaff the leprosarium and it was staffed by Catholic Sisters until its closure in 1982. The leprosy hospital was rebuilt on the mainland near the Quarantine Station in 1955 and developed into a happy institution under the direction of Dr. John Hargrave.

The R.A.A.F. sent Dr. Clyde Fenton back to the Northern Territory to form an aerial communications unit, firstly at Manbulloo near Katherine, then Batchelor and towards the end of the war the unit was at the civil airstrip (now Ross Smith Avenue). Other pilots joined Dr. Fenton using small Dragon biplanes. One of these was Flight-Lieutenant Jack Slade who remained after the war to re-establish an Aerial Medical Service based at Darwin. Army doctors flew with this unit to provide a medical service to the outback during the war. Jack Slade was discharged from the R.A.A.F. in April 1946 and was back to start the new service late in June. Sister Meryl Nichol joined the Aerial Medical Service in 1949, a role she filled for the next twelve years before marrying Captain Slade. Over the years more suitable aircraft came into use and the radio communication system was steadily transformed.

When the war ended suddenly in August 1945 the Department of Health was not prepared. Matron Mary (Holly) Roche, ex A.A.N.S. arrived on 4 April 1946 to help prepare the hospital which was run down. It had not been repaired after the bombing and all roofs leaked from the many holes made by flying debris. Equipment was worn out. Staff, including student nurses, were recruited interstate by public servants. Darwin had few houses; people lived in the earlier army camps, Vestey's meatworks, and anywhere they could find a roof to live under. The Aerial Medical Service pilot, Jack Slade and a doctor occupied the Pathological Laboratory. Newly arrived doctor's wives were appalled and wouldn't stay. It took several years to overcome the accommodation problem and even then the last of the army huts were not eradicated until the mid-1960s……..”

ELLEN KETTLE, M.B.E., F.C.N.A., DIP.N.AD.

Historian.

1986

The Commonwealth Government had big plans for development. The hospital was expanded and the first maternity ward was built. However, there was no reticulated water, everyone still relied on rain-water tanks, wells or bores. Two doctors were appointed to Aboriginal health surveys, and one of these, Dr. Mervyn Holmes became Chief Medical Officer and did a great deal to improve sanitation in the town. Dr. Holmes left many valuable reports; he also wrote a handbook on health for people in the outback and introduced medical kits on church missions, cattle stations and outback police stations. He prepared and introduced sound health legislation relevant to the tropics. At this time there were five trained nurses in the hospital.

The Administrator, Dr. J.A. Gilruth, a veterinary surgeon, had the go-ahead to develop experimental farms and to introduce good quality cattle and horses for breeding. The Vestey's Company, with large cattle properties was invited to build an abattoir on the site occupied by Darwin High School near the Museum. Hundreds of men came in as labourers and brought with them radical ideas. Communism was new and sweeping the world and strikes were the order of the day. As venereal diseases and alcohol were a considerable problem a compound was established for the Aborigines at Kahlin in 1912. Also the railway was extended and the men in camps demanded medical care but would not implement acceptable standards of hygiene or obey advice on the control of malaria.

World War broke out in Europe (1914-1918} and when finance was severely cut the unionists became even more aggressive. Malaria, dysentery and gonorrhoea were the biggest and most time consuming health problems. It can be said the Unions brought disaster; the abattoir only operated a couple of years and was then closed for ever. Poverty struck and the hospital had the role of caring for the destitute and many aging men from an earlier era.

In 1916 Dr. Holmes went to the War. He was replaced by Dr. Leighton Jones, who did his best but the situation was more than he could handle. The hospital became very run down and Matron Ethel Lang, a sweet but ineffective personality, was accused of letting the hospital be overrun by cats and poultry. At the time of Dr. Cecil Cook's arrival in 1927 the nursing staff had just resigned as a body in protest at the Matron's mismanagement. Dr. Cook accepted all the resignations but then began to realise a mistake had been made. Sister Constance Stone reconsidered and became the first Infant Health Sister in Darwin. Sister Olive Mansbridge stayed on as Matron until more staff could be recruited and Matron Lang's contract was not renewed.

Dr. Cecil Cook was young and arrogant and although he did much good work he also caused much strife. Matron Ida Ashburner took over in 1928 and continued at the hospital until her marriage in 1940. Dr. Cook introduced legislation for a Nurses Registration Board, Medical Board and the registration of dentists. Nurse training was introduced in 1929 using the syllabus for nurses in Queensland, an arrangement that continued until May 1964 when the training was changed to the New South Wales syllabus and examinations. There were six trained nurses and three doctors in Darwin, one of the doctors being Dr. Cecil Cook, the Chief Medical Officer. There was no mention of the purchase of any teaching aids and the hospital itself was old and primitive. Local girls were encouraged to train and the first to complete the course was Beatrice May Rogers in 1933. She went to Perth to do midwifery, married and did not return. By 1940 there were nine trainee nurses but as all records, including the Register disappeared during the war it is uncertain how many had completed training before 1942.

A new quarantine station was built on the mainland in 1929 and Channel Island was occupied as a leprosy hospital in 1931. Dr. Cook insisted that the leprosarium be staffed by a married couple, the wife being a trained nurse. In this he differed from the Government but he insisted and succeeded.

The patients from Mud Island and a group of mixed-race women who were at Darwin Hospital moved to Channel Island in August 1931, about 40 people in all. A few months later patients started to arrive from Western Australia and continued to do so until Western Australia built a hospital at Derby in 1940.

In 1935 hospitals were developed at Katherine and Tennant Creek. In 1939 the first Government hospital was opened at Alice Springs to replace the small hospital run by the Australian Inland Mission. March 1934 saw the arrival of Dr. Clyde Fenton with his own aircraft. He started an Aerial Medical Service from Katherine and was paid six pence per mile for his aeroplane. Dr. Fenton loved adventure and took many hair-raising risks in rescuing sick people. There was no radio so he flew without it. He told people in the outback that if they cleared airstrips he would land in an emergency and he did. Once when blown off course he ran out of fuel and landed beside a billabong; it took searching aircraft many days to find him. After three crashes he could not afford another aeroplane.

In 1937 the Government bought an aeroplane having realised the life-saving value of this service. In May 1940, just as he was achieving some facilities at Katherine, he joined the R.A.A.F. Another pilot flew the aircraft and it crashed at Katherine in October 1940. An unconscious Sister Dorothy Black was rescued but the patient perished when the fuel burst into flame.

A financial recession known as the Great Depression struck Australia in the early 1930s and everyone took a cut in salary. Many were out of work and destitute people were once again looked after by the hospital. Dr. Cook introduced a Medical Benefits Fund and although he was directed not to coerce people, there is no doubt that he did so. He controlled the Fund himself and claimed it was a success but by 1939 it was heavily in debt and the scheme was placed in the hands of the Taxation Department to collect the money and pay the hospitals.

By the mid-1930s war became a real threat and Darwin began to develop as a military outpost. The civilian airstrip was on the site of Ross Smith Avenue and it was too small for the R.A.A.F. who in 1938 surveyed the present airport. The R.A.A.F. base was still being constructed when bombed in 1942. Army numbers increased and as they had no barracks they used Vestey's meatworks. Darwin was without reticulated water for the many thousands of men in the area until the pumps at the new Manton Dam were started on 10 March 1941. Prior to that the army put a small weir across Howard Springs and pumped water from there this facility still remains.

Darwin Hospital was soon grossly inadequate in both space and equipment. Plans were drawn up for a new hospital but experts who visited from Canberra decided that Canberra had a more urgent need for a hospital than Darwin. The hospital design allowed for two infectious wards and in 1938 Dr. Cook had these built on the Kahlin Compound site to isolate and treat venereal diseases. A new settlement for the Aborigines was built at Bagot and as they moved on to this site in 1939 the Army took over Kahlin Compound for a tent hospital. At that time dengue fever was a considerable problem and as men were away from home they had to be nursed in hospital. Even the doctors developed dengue fever.

On 3 September 1939 war started in Europe but men in the armed services recognized a threat nearer home as the Japanese were arming and being aggressive. In December the heads of the three services in Darwin, Army, R.A.A.F. and Navy, jointly signed a letter to the Minister for the Army demanding a new hospital in Darwin. Parliament approved the funds in June 1940 and work commenced on the Kahlin Compound site about January 1941. All building supplies were delayed by militant wharf laborers and this continued after Japan entered the war.

As the old Darwin Hospital could not cope the Army took over Bagot Aboriginal settlement where there were buildings and developed 119 A.G.H. there with a staff of forty Sisters and about one hundred orderlies. The Aborigines were sent across the harbour to Delissaville. Most of 119 A.G.H. was canvas and the site was not suitable but the need was urgent. The R.A.A.F. built its own small hospital with a doctor and six Sisters while the Navy planned to use a wing of the new Darwin Hospital when it was completed.

Sister Edith McQuade White, who had been with the Northern Territory hospitals since 1936, joined the army and became the matron of 119 A.G.H. Later, in mid-1942 she was the Principal Matron in charge of A.A.N.S. in the Northern Territory. When she went to New Guinea late in 1943 she was replaced by Matron Susan Haines.

The Army built a new hospital at Berrimah (Kormilda College site) and moved the medical section there on 1 January 1942 long before the buildings were completed. Japan attacked Pearl Harbour on 8 December 1941. Orders were given for women and children to be evacuated from Darwin. Most went out by ship as there was no highway while others who could afford to pay went by Catalina flying boat. It was a distressing time as many people had no family connections in the south. Darwin, being frontline, was placed under strict censorship and the newspaper printed no local news.

Nursing staff and a few other women in key work such as the Post Office were permitted to stay. By January 1942 there were thousands of Americans in Darwin pending further orders. The equipment, X-ray included, did not arrive for the new Darwin Hospital but the need was desperate and the hospital was occupied on 2 February 1942. The Army loaned a mobile X-ray unit and the Americans loaned 150 beautiful quality beds. A few months later the Americans needed the beds and Darwin Hospital was issued with low folding army beds.

The hospital ship “Manunda” came into Darwin Harbour on 16 January pending further orders. At 10 a.m. on 19 February 1942 the aircraft from the same four aircraft carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbour mercilessly attacked Darwin. Three American aircraft hit back but were outnumbered. No Australian aircraft got off the ground.

There were five functional hospitals in Darwin and all received damage. In spite of the red crosses on the roof eight bombs fell in the vicinity of Darwin Hospital; two outside Ward 1. wrecked the end of the ward. The R.A.A.F. hospital was destroyed but all the staff were in slit trenches and survived.

Berrimah (119 A.G.H.) was deliberately strafed by aircraft and one man, too sick to be moved to a slit trench. was killed.

Bagot (119 A.G.H. surgical) was caught in the hail of bullets fired at an American aircraft trying to get aloft - the pilot bailed out and was brought in as a patient next day. The X-ray unit at Bagot was put out of action by a bullet. "Manunda” in the harbour was deliberately attacked twice. A bomb went through the skylight of the music room and exploded at C. Deck, killing twelve. Two others died a couple of days later. Sister Margaret De Mestre was mortally wounded and Sister Lorraine Blow was dangerously wounded. Their dentist was killed outright. After the all clear siren sounded Army ambulances took the wounded to Bagot and Berrimah while civilians in town found their way to Darwin Hospital. In spite of four internal fires ''Manunda" continued to function and admitted over seventy patients direct from the ships sunk in the harbour. Lifeboats from "Manunda“ worked overtime and two of the crew were wounded in the boats when strafed by the enemy.

A Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service had not been established in Darwin and there were no intravenous fluids or blood transfusions given as the equipment was not adequate. The first Soluvac saline and glucose became available in July 1942. Lieutenant-Commander Sam Sewell (R.A.N.) brought in a Julien Smith direct transfusion set ten days later and then if a man was wounded during an air raid a mate with the same blood group was to accompany him to hospital this worked well for both civilians and servicemen.

On 20 February, the day after the bombing, Surgeon-Commander Clive James authorised the evacuation in "Manunda" of all the wounded from Darwin. He did not have this authority and was dismissed from the Navy a few days later. Most of the wounded were too ill to be moved but once the action of loading the ship had started it had to continue. The wharf had been destroyed so patients were taken by lifeboats and the lifeboats were then lifted to the required deck for transfer. The ship’s lift was out of action. "Manunda" sailed that night, looking like a porcupine with dunnage poking out of seventy holes in the hull. Matron Claire Schumach specialled Sister Blow whose condition was dangerous; this left 14 Sisters and about 100 orderlies to care for 260 other casualties. Major Keith Bowden was the only surgeon in the ship - "Manunda" was not meant to carry front line battle casualties. The laundry was out of action and much of the ships fresh water had been lost due to perforated water lines and fighting fires within the ship. Fifteen patients, most of whom had suffered extensive burns, died in the ship on the way to Fremantle.

Back in Darwin the police and the Army hygiene teams counted and buried the dead. When the deaths in "Manunda" are included, over 300 lives were lost. The Post Office staff were all killed when struck by a bomb, while most of the other casualties were from among the wharf laborers and the crews of sunken ships. The original Darwin Hospital became the living quarters for the hundreds of sailors stranded without ships.

Darwin Hospital was taken over by the Army and Dr. Bruce Kirkland, the Chief Medical Officer joined the Army in June and became Commanding Officer in 129 A.G.H; (Darwin Hospital). The civilian nursing staff were sent south and the hospital was without women again until December 1942. The Army hospitals (Bagot and Berrimah) were moved inland to Adelaide River where conditions were very primitive for many months. An Army hospital (121 A.G.H.) was established at Katherine while Tennant Creek and Alice Springs were also taken over.

The leprosarium on Channel Island was not bombed but Matron Elsie Jones was ill and she went south on the train five days after the bombing. When she reached Tennant Creek she left the convoy to stay with friends at Rockhampton Downs, 112 kilometres from Tennant Creek. On 10 March she became acutely ill and Dr. W. Straede and his wife went out by car to rescue her. The Straede's car broke down and both perished from thirst in that hot dry country. The next day Elsie Jones was flown out by the Flying Doctor Service from Cloncurry; she died in Brisbane Hospital on 17 May 1942. Elsie Jones, as Sister King, had been the first Sister at Victoria River Downs during a devastating

outbreak of malaria in 1922; she had travelled there by horse and buggy.

For the first two years of the war the Army hospitals were immensely busy. Over Christmas 1942 to New Year 1943 both Adelaide River and Katherine Hospitals peaked at over 900 inpatients. Many were refugee women and children from Indonesia, and most had dysentery or malaria or both. An ambulance train, comprising converted cattle trucks, moved the patients down the line to make room for more that train was bombed while at Adelaide River and a medical orderly was killed·. The Americans brought in their own hospitals to look after their airmen; their largest hospital was at Nightcliff.

In April 1943 the first two Catholic Nursing Sisters arrived to restaff the leprosarium and it was staffed by Catholic Sisters until its closure in 1982. The leprosy hospital was rebuilt on the mainland near the Quarantine Station in 1955 and developed into a happy institution under the direction of Dr. John Hargrave.

The R.A.A.F. sent Dr. Clyde Fenton back to the Northern Territory to form an aerial communications unit, firstly at Manbulloo near Katherine, then Batchelor and towards the end of the war the unit was at the civil airstrip (now Ross Smith Avenue). Other pilots joined Dr. Fenton using small Dragon biplanes. One of these was Flight-Lieutenant Jack Slade who remained after the war to re-establish an Aerial Medical Service based at Darwin. Army doctors flew with this unit to provide a medical service to the outback during the war. Jack Slade was discharged from the R.A.A.F. in April 1946 and was back to start the new service late in June. Sister Meryl Nichol joined the Aerial Medical Service in 1949, a role she filled for the next twelve years before marrying Captain Slade. Over the years more suitable aircraft came into use and the radio communication system was steadily transformed.

When the war ended suddenly in August 1945 the Department of Health was not prepared. Matron Mary (Holly) Roche, ex A.A.N.S. arrived on 4 April 1946 to help prepare the hospital which was run down. It had not been repaired after the bombing and all roofs leaked from the many holes made by flying debris. Equipment was worn out. Staff, including student nurses, were recruited interstate by public servants. Darwin had few houses; people lived in the earlier army camps, Vestey's meatworks, and anywhere they could find a roof to live under. The Aerial Medical Service pilot, Jack Slade and a doctor occupied the Pathological Laboratory. Newly arrived doctor's wives were appalled and wouldn't stay. It took several years to overcome the accommodation problem and even then the last of the army huts were not eradicated until the mid-1960s……..”

ELLEN KETTLE, M.B.E., F.C.N.A., DIP.N.AD.

Historian.

1986