FIRST CONTACT

The East Arnhem Perspective

Wurramala - Whale Hunters

Yolngu oral history identifies waves of visitors to NE Arnhemland beginning with whale hunters (Wurramala), some of whom can be positively linked to the Sea Gypsies or Sama Bajau.

Pre-Macassans

Then there are the Pre-Macassans or Bayini (from the Sultanates of Gowa and Tallo) who controlled a good portion of eastern Indonesia prior to their defeat by Dutch/Bugis forces in 1667.

It is during the Pre-Macassan (Gowa-Tallo) era that songs, ceremonies and names pertaining to enormous power struggles underway in the waters to Australia’s north, namely Islam versus Christianity, English versus Dutch traders, and indigenous resistance to the lot, first appear in the Yolngu lexicon. Personal names like Gumpaniya, for example, are a direct reference to the awesome authority wielded by the VOC (Dutch East India Company) throughout the region. Yolngu understood these dynamics and interpreted them through their own cultural lens in innumerable ways, still visible in their communities.

It is during the Pre-Macassan (Gowa-Tallo) era that songs, ceremonies and names pertaining to enormous power struggles underway in the waters to Australia’s north, namely Islam versus Christianity, English versus Dutch traders, and indigenous resistance to the lot, first appear in the Yolngu lexicon. Personal names like Gumpaniya, for example, are a direct reference to the awesome authority wielded by the VOC (Dutch East India Company) throughout the region. Yolngu understood these dynamics and interpreted them through their own cultural lens in innumerable ways, still visible in their communities.

Macassans

In the late 1700s, the Macassan trepang industry began and there were two waves, the early and late, finishing in 1907.

The Macassan trepang era, by contrast, did not feature a similar exchange of ideas and deep culture, and is far less significant. As Yolngu elders say, the early visitors were on sacred business. The latter trepangers were simply businessmen.

Early Encounters between Aboriginals & Europeans

Cook's Orders

Capt. James Cook 1776 by N. Dance Greenwich Maritime Museum

Capt. James Cook 1776 by N. Dance Greenwich Maritime Museum

"Whereas there is reason to imagine that a Continent or Land of great extent may be found to the Southward of the Tract lately made by Captn Wallis in His Majesty’s Ship the Dolphin (of which you will herewith receive a Copy) or of the Tract of any former Navigators in Pursuit of the like kind, You are therefore in Pursuance of His Majesty’s Pleasure hereby requir’d and directed to put to Sea with the Bark you Command so soon as the Observation of the Transit of the Planet Venus shall be finished and observe the following Instructions. You are to proceed to the Southward in order to make discovery of the Continent abovementioned until’ you arrive in the Latitude of 40°, unless you sooner fall in with it. But not having discover’d it or any Evident sign of it in that Run you are to proceed in search of it to the Westward between the Latitude beforementioned and the Latitude of 35° until’ you discover it, or fall in with the Eastern side of the Land discover’d by Tasman and now called New Zeland.

If you discover the Continent abovementioned either in your Run to the Southward or to the Westward as above directed, You are to employ yourself diligently in exploring as great an Extent of the Coast as you can, carefully observing the true situation thereof both in Latitude and Longitude, the Variation of the Needle; bearings of Head Lands Height direction and Course of the Tides and Currents, Depths and Soundings of the Sea, Shoals, Rocks and also surveying and making Charts, and taking Views of Such Bays, Harbours and Parts of the Coasts as may be useful to Navigation. You are also carefully to observe the Nature of the Soil, and the Products thereof; the Beasts and Fowls that inhabit or frequent it, the Fishes that are to be found in the Rivers or upon the Coast and in what Plenty, and in Case you find any Mines, Minerals, or valuable Stones you are to bring home Specimens of each, as also such Specimens of the Seeds of the Trees, Fruits and Grains as you may be able to collect, and Transmit them to our Secretary that We may cause proper Examination and Experiments to be made of them.

You are likewise to observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the Natives, if there be any, and endeavour by all proper means to cultivate a Friendship and Alliance with them, making them presents of such Trifles as they may Value, inviting them to Traffick, and Shewing them every kind of Civility and Regard; taking Care however not to suffer yourself to be surprized by them, but to be always upon your guard against any Accidents. You are also with the Consent of the Natives to take Possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain: Or: if you find the Country uninhabited take Possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors."

If you discover the Continent abovementioned either in your Run to the Southward or to the Westward as above directed, You are to employ yourself diligently in exploring as great an Extent of the Coast as you can, carefully observing the true situation thereof both in Latitude and Longitude, the Variation of the Needle; bearings of Head Lands Height direction and Course of the Tides and Currents, Depths and Soundings of the Sea, Shoals, Rocks and also surveying and making Charts, and taking Views of Such Bays, Harbours and Parts of the Coasts as may be useful to Navigation. You are also carefully to observe the Nature of the Soil, and the Products thereof; the Beasts and Fowls that inhabit or frequent it, the Fishes that are to be found in the Rivers or upon the Coast and in what Plenty, and in Case you find any Mines, Minerals, or valuable Stones you are to bring home Specimens of each, as also such Specimens of the Seeds of the Trees, Fruits and Grains as you may be able to collect, and Transmit them to our Secretary that We may cause proper Examination and Experiments to be made of them.

You are likewise to observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the Natives, if there be any, and endeavour by all proper means to cultivate a Friendship and Alliance with them, making them presents of such Trifles as they may Value, inviting them to Traffick, and Shewing them every kind of Civility and Regard; taking Care however not to suffer yourself to be surprized by them, but to be always upon your guard against any Accidents. You are also with the Consent of the Natives to take Possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain: Or: if you find the Country uninhabited take Possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors."

Endeavour River 1770 - The Broken Spear Myth

"Not long before he died a couple of years ago at the age of 91, the ANU’s great historian, Professor John Molony, took me aside at the National Library to tell me of an episode involving Captain Cook which he maintained should be known by all Australians – an event in our history that could be the key to healing that weeping wound on the national soul that stems from our deeply troubled history." Sydney morning Herald, Peter Fitzsimons 18/07/2020.

"It is, as Joseph Banks describes him, “a little old man", and he is carrying a deliberately broken spear, its once-dangerous spear-head now lying at a limp right-angle to the main shaft.

Several times he stops. But, encouraged by the white men beckoning him forward, he always starts approaching again, until – with extraordinary bravery and unwavering resolution – he stands before them, still holding his broken spear.

This man, a deeply respected tribal elder by the name of Ngamu Yarrbarigu, speaks to them. “Ngahthaan gadaai thawun maa naa thi hu,” he says. “We come to make friends.”

Of course, none of the Endeavour men can understand a word. Nevertheless, it is clear his broken spear is a gesture of peace. The little old man goes on to explain in his curious sign language what he wants. He uses a curious mannerism that includes, as described by Joseph Banks, “drawing moisture from under his armpits [and] blowing the sweat on his hands into the air”.

Unknown to the white men, he is performing a ritual known as “ngaala ngan daamal mal”, my sweat from me sent to you, a call for calm.

Hence Professor Molony’s point to me: The gesture of the tribal elder, and the broken spear he proffered, should be our national motif, a symbol on our coins, our currency, and maybe even our flag. Some nations want lots of spears, others want powerful spears that can destroy nations on the other side of the world. We are the people of the broken spears. We want to live together in peace with each other, and with the world."

Several times he stops. But, encouraged by the white men beckoning him forward, he always starts approaching again, until – with extraordinary bravery and unwavering resolution – he stands before them, still holding his broken spear.

This man, a deeply respected tribal elder by the name of Ngamu Yarrbarigu, speaks to them. “Ngahthaan gadaai thawun maa naa thi hu,” he says. “We come to make friends.”

Of course, none of the Endeavour men can understand a word. Nevertheless, it is clear his broken spear is a gesture of peace. The little old man goes on to explain in his curious sign language what he wants. He uses a curious mannerism that includes, as described by Joseph Banks, “drawing moisture from under his armpits [and] blowing the sweat on his hands into the air”.

Unknown to the white men, he is performing a ritual known as “ngaala ngan daamal mal”, my sweat from me sent to you, a call for calm.

Hence Professor Molony’s point to me: The gesture of the tribal elder, and the broken spear he proffered, should be our national motif, a symbol on our coins, our currency, and maybe even our flag. Some nations want lots of spears, others want powerful spears that can destroy nations on the other side of the world. We are the people of the broken spears. We want to live together in peace with each other, and with the world."

The Endeavour Journal of Sir Joseph Banks

"1770 July 19.

Ten Indians visited us today and brought with them a larger quantity of Lances than they had ever done before, these they laid up in a tree leaving a man and a boy to take care of them and came on board the ship. They soon let us know their errand which was by some means or other to get one of our Turtle of which we had 8 or 9 laying upon the decks. They first by signs askd for One and on being refusd shewd great marks of Resentment; one who had askd me on my refusal stamping with his foot pushd me from him with a countenance full of disdain and applyd to some one else; as however they met with no encouragement in this they laid hold of a turtle and hauld him forwards towards the side of the ship where their canoe lay. It however was soon taken from them and replacd. They nevertheless repeated the expiriment 2 or 3 times and after meeting with so many repulses all in an instant leapd into their Canoe and went ashore where I had got before them Just ready to set out plant gathering; they seizd their arms in an instant, and taking fire from under a pitch kettle which was boiling they began to set fire to the grass to windward of the few things we had left ashore with surprizing dexterity and quickness; the grass which was 4 or 5 feet high and as dry as stubble burnt with vast fury. A Tent of mine which had been put up for Tupia when he was sick was the only thing of any consequence in the way of it so I leapd into a boat to fetch some people from the ship in order to save it, and quickly returning hauld it down to the beach Just time enough. The Captn in the meantime followd the Indians to prevent their burning our Linnen and the Seine which lay on the grass just where they were gone. He had no musquet with him so soon returnd to fetch one for no threats or signs would make them desist. Mine was ashore and another loaded with shot, so we ran as fast as possible towards them and came just time enough to save the Seine by firing at an Indian who had already fird the grass in two places just to windward of it; on the shot striking him, tho he was full 40 yards from the Captn who fird, he dropd his fire and ran nimbly to his comrades who all ran off pretty fast. The Captn then loaded his musquet with a ball and fird it into the Mangroves abreast of where they ran to shew them that they were not yet out of our reach, they ran on quickning their pace on hearing the Ball and we soon lost sight of them; we then returnd to the Seine where the people who were ashore had got the fire under. We now thought we were free'd from these troublesome people but we soon heard their voices returning on which, anxious for some people who were washing that way, we ran towards them; on seeing us come with our musquets they again retird leasurely after an old man had venturd quite to us and said something which we could not understand. We followd for near a mile, then meeting with some rocks from whence we might observe their motions we sat down and they did so too about 100 yards from us. The little old man now came forward to us carrying in his hand a lance without a point. He halted several times and as he stood employd himself in collecting the moisture from under his arm pit with his finger which he every time drew through his mouth. We beckond to him to come: he then spoke to the others who all laid their lances against a tree and leaving them came forwards likewise and soon came quite to us. They had with them it seems 3 strangers who wanted to see the ship but the man who was shot at and the boy were gone, so our troop now consisted of 11. The Strangers were presented to us by name and we gave them such trinkets as we had about us; then we all proceeded towards the ship, they making signs as they came along that they would not set fire to the grass again and we distributing musquet balls among them and by our signs explaining their effect. When they came abreast of the ship they sat down but could not be prevaild upon to come on board, so after a little time we left them to their contemplations; they stayd about two hours and then departed.

We had great reason to thank our good Fortune that this accident happned so late in our stay, not a week before this our powder which was put ashore when first we came in had been taken on board, and that very morning only the store tent and that in which the sick had livd were got on board. I had little Idea of the fury with which the grass burnt in this hot climate, nor of the dificulty of extinguishing it when once lighted: this accident will however be a sufficient warning for us if ever we should again pitch tents in such a climate to burn Every thing round us before we begin.

1770 July 23.

In Botanizing today on the other side of the river we accidentaly found the greatest part of the clothes which had been given to the Indians left all in a heap together, doubtless as lumber not worth carriage. May be had we lookd farther we should have found our other trinkets, for they seemd to set no value upon any thing we had except our turtle, which of all things we were the least able to spare them."

Ten Indians visited us today and brought with them a larger quantity of Lances than they had ever done before, these they laid up in a tree leaving a man and a boy to take care of them and came on board the ship. They soon let us know their errand which was by some means or other to get one of our Turtle of which we had 8 or 9 laying upon the decks. They first by signs askd for One and on being refusd shewd great marks of Resentment; one who had askd me on my refusal stamping with his foot pushd me from him with a countenance full of disdain and applyd to some one else; as however they met with no encouragement in this they laid hold of a turtle and hauld him forwards towards the side of the ship where their canoe lay. It however was soon taken from them and replacd. They nevertheless repeated the expiriment 2 or 3 times and after meeting with so many repulses all in an instant leapd into their Canoe and went ashore where I had got before them Just ready to set out plant gathering; they seizd their arms in an instant, and taking fire from under a pitch kettle which was boiling they began to set fire to the grass to windward of the few things we had left ashore with surprizing dexterity and quickness; the grass which was 4 or 5 feet high and as dry as stubble burnt with vast fury. A Tent of mine which had been put up for Tupia when he was sick was the only thing of any consequence in the way of it so I leapd into a boat to fetch some people from the ship in order to save it, and quickly returning hauld it down to the beach Just time enough. The Captn in the meantime followd the Indians to prevent their burning our Linnen and the Seine which lay on the grass just where they were gone. He had no musquet with him so soon returnd to fetch one for no threats or signs would make them desist. Mine was ashore and another loaded with shot, so we ran as fast as possible towards them and came just time enough to save the Seine by firing at an Indian who had already fird the grass in two places just to windward of it; on the shot striking him, tho he was full 40 yards from the Captn who fird, he dropd his fire and ran nimbly to his comrades who all ran off pretty fast. The Captn then loaded his musquet with a ball and fird it into the Mangroves abreast of where they ran to shew them that they were not yet out of our reach, they ran on quickning their pace on hearing the Ball and we soon lost sight of them; we then returnd to the Seine where the people who were ashore had got the fire under. We now thought we were free'd from these troublesome people but we soon heard their voices returning on which, anxious for some people who were washing that way, we ran towards them; on seeing us come with our musquets they again retird leasurely after an old man had venturd quite to us and said something which we could not understand. We followd for near a mile, then meeting with some rocks from whence we might observe their motions we sat down and they did so too about 100 yards from us. The little old man now came forward to us carrying in his hand a lance without a point. He halted several times and as he stood employd himself in collecting the moisture from under his arm pit with his finger which he every time drew through his mouth. We beckond to him to come: he then spoke to the others who all laid their lances against a tree and leaving them came forwards likewise and soon came quite to us. They had with them it seems 3 strangers who wanted to see the ship but the man who was shot at and the boy were gone, so our troop now consisted of 11. The Strangers were presented to us by name and we gave them such trinkets as we had about us; then we all proceeded towards the ship, they making signs as they came along that they would not set fire to the grass again and we distributing musquet balls among them and by our signs explaining their effect. When they came abreast of the ship they sat down but could not be prevaild upon to come on board, so after a little time we left them to their contemplations; they stayd about two hours and then departed.

We had great reason to thank our good Fortune that this accident happned so late in our stay, not a week before this our powder which was put ashore when first we came in had been taken on board, and that very morning only the store tent and that in which the sick had livd were got on board. I had little Idea of the fury with which the grass burnt in this hot climate, nor of the dificulty of extinguishing it when once lighted: this accident will however be a sufficient warning for us if ever we should again pitch tents in such a climate to burn Every thing round us before we begin.

1770 July 23.

In Botanizing today on the other side of the river we accidentaly found the greatest part of the clothes which had been given to the Indians left all in a heap together, doubtless as lumber not worth carriage. May be had we lookd farther we should have found our other trinkets, for they seemd to set no value upon any thing we had except our turtle, which of all things we were the least able to spare them."

Captain Cook & the Kilora Medal, Bruny Island 1777

Captain James Cook in HMS Resolution & Captain Tobias Furneaux in HMS Adventure left England in 1772 to explore the South Seas. Becoming separated, Furneaux followed Tasman's chart and in 1773 discovered and named Adventure Bay - he replenished water & wood supplies and sailed on to New Zealand. Cook landed at Adventure Bay in 1777 from H. M. S. "Resolution" with William Bligh as sailing master. Bligh returned in 1788 with botanist Nelson and on the eastern side of the bay he planted fruit trees from the Cape of Good Hope. Returning in 1792, all but one had been burned out and it is said to be the first Granny Smith apple tree. Tasmania become known as Australia's Apple Isle. The last resident full blood Tasmanian aboriginal, Truganini, belonged to a Bruny Island tribe.

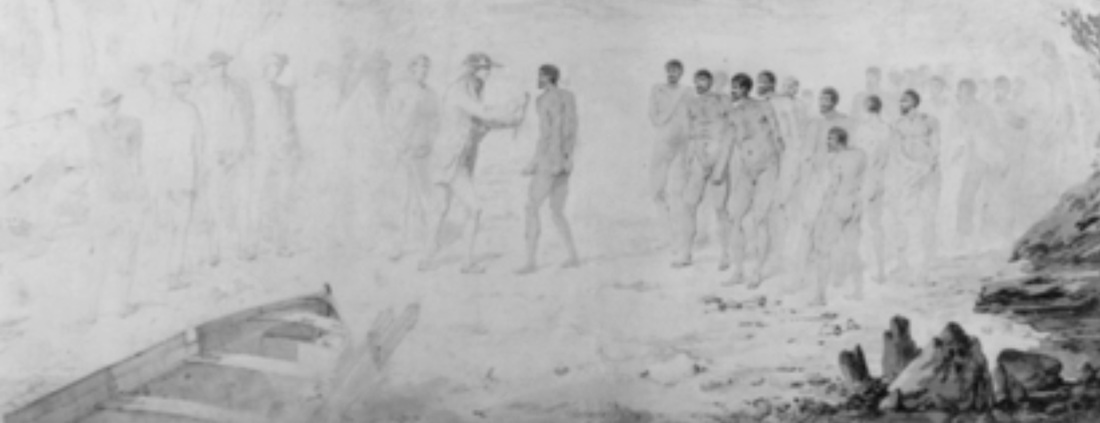

Between 26 January and 30 January 1777, 11 years before the First Fleet arrived in Australia, Captain Cook visited Adventure Bay to obtain supplies of wood and water. On 28 January, whilst a shore party was cutting wood, Cook met and gave presents to 'natives, eight men and a boy'. The following day, while on board the Resolution, Cook sighted 20 Aboriginal people on the beach. He took a group of men ashore, where they distributed gifts of iron tools, beads, medals, and fishhooks. Cook later wrote in his journal, 'I gave each of them a string of Beads and a Medal, which I thought they received with some satisfaction'. This is the meeting that features in John Webber's sketch (above) showing Cook with arms outstretched and about to place a medal around the neck of an Aboriginal man. To the left of Cook is the landing party of officers and sailors and to his right a group of about 20 Aboriginal people. This drawing is the first to illustrate Europeans and Aborigines together, in a meeting which took place at Adventure Bay on Bruny Island, Tasmania.

Peter Lane holding the Killora medal.

Peter Lane holding the Killora medal.

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War, Janet Cadell, a four-year-old girl, found the medal while her father was ploughing his property at Killora on Bruny Island, at the opposite end of the island from Adventure Bay.

She was walking behind her father, collecting worms 'to feed her chooks' when she stumbled on the medal, with its suspension ring attached to it (the ring has long since been lost). It shows virtually no signs of wear, suggesting that it was either lost or discarded shortly after being given. The medal is made of bronze, with a high zinc content, and would have been bright and shiny like a newly minted penny. Her father, JL Cadell, recognised the significance of the medal and reported the find to the Hobart Mercury.

The newspaper published the discovery on 1 December 1914 on page four, but Janet's name was not mentioned; her father was recorded as the finder. The story of the find was retold in the Mercury on 20 February 1924.

Image shows (L>R) Peter Lane holding the Killora medal - the late Tom Hanley, Australian Numismatic Society secretary & the late Mrs Janet Millar (nee Cadell) finder of the medal, c1996

She was walking behind her father, collecting worms 'to feed her chooks' when she stumbled on the medal, with its suspension ring attached to it (the ring has long since been lost). It shows virtually no signs of wear, suggesting that it was either lost or discarded shortly after being given. The medal is made of bronze, with a high zinc content, and would have been bright and shiny like a newly minted penny. Her father, JL Cadell, recognised the significance of the medal and reported the find to the Hobart Mercury.

The newspaper published the discovery on 1 December 1914 on page four, but Janet's name was not mentioned; her father was recorded as the finder. The story of the find was retold in the Mercury on 20 February 1924.

Image shows (L>R) Peter Lane holding the Killora medal - the late Tom Hanley, Australian Numismatic Society secretary & the late Mrs Janet Millar (nee Cadell) finder of the medal, c1996

Even less well known than John Webber's drawing is the medal it features. This medal and the others distributed at the same time were among the earliest gifts given by Europeans to Aborigines and symbolise both the idealism and the reality of our country's pre-colonisation encounters. The Webber drawing also provides the only known record of Aboriginal people being presented with medals. The sketch is unique in a larger sense; no other contemporary drawing was made of medals being presented to anyone during Cook's second or third voyages.

Up until the late 1960s Mrs Janet Millar (née Cadell) simply kept her medal in a safe place, and never intended to sell it until approached by Sir William Crowther, Hobart medical practitioner, collector of Tasmaniana and major donor to the State Library of Tasmania. She sold the medal to him for $60 and assumed that it would remain in Tasmania. On 26 January 1977, to mark the bicentenary of Captain Cook's landing at Adventure Bay, the State Library of Tasmania celebrated the event with an exhibition of pictures, books, maps and other material relating to sea explorers who had visited Tasmania. The items were mainly borrowed from public institutions and Sir William Crowther's collection. One of the highlights was his Cook medal and the opening address told the story of how he had located it. The display ran from 26 January to 9 February 1977.

Crowther's numismatic collection, including the Cook medal, was sold by auction shortly after his death in 1981. Despite its pre-auction estimate of $500, Crowther's medal was sold to L Richard Smith, a Captain Cook enthusiast, for $1300 — an unheard-of price for those times. The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery had one that they believed was found in Tasmania and were interested in a second example. It was later discovered that their records revealed that their example had been distributed to a Pacific Islander and came by way of the Tasmanian Royal Society.

Crowther's numismatic collection, including the Cook medal, was sold by auction shortly after his death in 1981. Despite its pre-auction estimate of $500, Crowther's medal was sold to L Richard Smith, a Captain Cook enthusiast, for $1300 — an unheard-of price for those times. The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery had one that they believed was found in Tasmania and were interested in a second example. It was later discovered that their records revealed that their example had been distributed to a Pacific Islander and came by way of the Tasmanian Royal Society.

PastMaster Peter Lane recalls - "Smith wrote a book on Cook’s medals but did not research the history of this medal. Smith and I became good friends when I alerted him to a document related to Sir Thomas Brisbane. In 1991 he decided to sell his collection including the Killora example as one lot and he was aware that I was very keen to acquire the medal so he informed me of the pending auction; he had visions it would be acquired by a major institution. I did not bid as it was well over my budget and the lot did not find a buyer. Afterwards Smith sold me the Killora medal. Once acquired I discovered its provenance and met Janet Cadell, who by that time was living in Sydney. When I visited her, Tom Hanley who had given the valuation and Les Carlisle who helped me track her down were present."

The medal went on display at the South Australian Museum and is recorded in Philip Jones book Ochre and Rust. The medal will shortly be on display at the Art Gallery of South Australia where Peter Lane is the honorary curator of numismatics.

The medal went on display at the South Australian Museum and is recorded in Philip Jones book Ochre and Rust. The medal will shortly be on display at the Art Gallery of South Australia where Peter Lane is the honorary curator of numismatics.

HMS Beagle - Port Darwin

A Visit from the Natives - Shoal Bay 1839

"The Beagle anchored at Hope Inlet in Shoal Bay on 8th Sept 1839 - 'During the time we were absent, some of our people who had been on shore, received a visit from a party of natives, who evinced the most friendly disposition.

Those people amounted in number, with their families, to twenty-seven, and came down to our party without any symptoms of hesitation. Both men and women were finer than those we had seen in Adam Bay. The tallest male measured five feet eleven, which is three inches less than a native Flinders measured in the Gulf of Carpentaria. The teeth of these people were ALL PERFECT. (i.e. none knocked out)

They had clearly never seen a white person before; for they stepped up to one man of fair complexion, who had his trousers turned up over his knees, and began rubbing his skin to see whether it was painted.

These were presumably Tiwi Islands people as One Tree Point and the peninsular up to and including the Vernon Islands is Tiwi land though this is of course disputed." John Lort Stokes, Journal of a Voyage of Discovery Vol 2 Ch2.1

Those people amounted in number, with their families, to twenty-seven, and came down to our party without any symptoms of hesitation. Both men and women were finer than those we had seen in Adam Bay. The tallest male measured five feet eleven, which is three inches less than a native Flinders measured in the Gulf of Carpentaria. The teeth of these people were ALL PERFECT. (i.e. none knocked out)

They had clearly never seen a white person before; for they stepped up to one man of fair complexion, who had his trousers turned up over his knees, and began rubbing his skin to see whether it was painted.

These were presumably Tiwi Islands people as One Tree Point and the peninsular up to and including the Vernon Islands is Tiwi land though this is of course disputed." John Lort Stokes, Journal of a Voyage of Discovery Vol 2 Ch2.1

A Second Visit by the Natives - Shoal Bay 1839

24th Sept on Pt Emery - "Their voices, shrill like those of all their fellows, were heard before they were seen. With these it was particularly so, though on all occasions the speaking, and hallooing of the Aborigines can be heard at a very considerable distance. They were found, when on shore, to be of the party we had before seen in Shoal Bay, with the addition of five strange men. All appeared actuated by the same friendly disposition, a very strong indication of which was their presenting themselves without spears. Like most others on that coast, they had a piece of bamboo, eighteen inches long, run through the cartilage of the nose.

Their astonishment at the size of the wells was highly amusing; sudden exclamations of surprise and admiration burst from their lips, while the varied expressions and play of countenance, showed how strongly their feelings were at work within.

At length by stretching their spare bodies and necks to the utmost, they caught sight of the water in the bottom. The effect upon them was magical, and they stood at first as if electrified. At length their feelings gained vent, and from their lips proceeded an almost mad shout of delight. Perhaps their delight may be considered a sign how scarce is water in this part of the country. I should certainly say from the immense quantity each man drank, which was two quarts, that this was the case. When gazing on the superabundant water that flows in almost every corner of the earth, we cannot but reflect on the scantily supplied Australian, nor fail to wish him a more plentiful supply." John Lort Stokes, Journal of a Voyage of Discovery Vol 2 Ch2.1

Their astonishment at the size of the wells was highly amusing; sudden exclamations of surprise and admiration burst from their lips, while the varied expressions and play of countenance, showed how strongly their feelings were at work within.

At length by stretching their spare bodies and necks to the utmost, they caught sight of the water in the bottom. The effect upon them was magical, and they stood at first as if electrified. At length their feelings gained vent, and from their lips proceeded an almost mad shout of delight. Perhaps their delight may be considered a sign how scarce is water in this part of the country. I should certainly say from the immense quantity each man drank, which was two quarts, that this was the case. When gazing on the superabundant water that flows in almost every corner of the earth, we cannot but reflect on the scantily supplied Australian, nor fail to wish him a more plentiful supply." John Lort Stokes, Journal of a Voyage of Discovery Vol 2 Ch2.1

Natives on a Raft - Port Darwin 1839

NMA-11791- Basedow Collection George Water WA 1916

NMA-11791- Basedow Collection George Water WA 1916

"At the turning leading from the outer to the inner harbour they came suddenly in view of a raft making across, a distance of three miles, on which were two women with several children, whilst four or five men were swimming alongside, towing it and supporting themselves by means of a log of wood across their chests. On perceiving the boat they instantly struck out for the land leaving the women on the raft. For some time the latter kept their position, waiting until the boat got quite near, when they gave utterance to a dreadful yell, and assuming at the same time a most demoniacal aspect, plunged into the water as if about to abandon the children to their fate.

Not so, however; despite the dreadful fear they appeared to entertain of the white man, maternal affection was strong within them, and risking all to save their offspring, they began to tow the raft with all their strength towards the shore. This devotion on the part of the women to their little ones, was in strong contrast with the utter want of feeling shown by the men towards both mothers and children.

Captain Wickham now, no doubt to their extreme consternation, pulled after the men, and drove them back to the raft. Some dived and tried thus to escape the boat, while others grinned ferociously, and appeared to hope, by dint of hideous grimaces--such as are only suggested even to a savage by the last stage of fear--to terrify the white men from approaching. At length, however, they were all driven back to the raft, which was then towed across the harbour for them; a measure which they only were able to approve of when they had landed, and fear had quite subsided.

Doubtless, the forbearance of our party surprised them, for from their terrified looks and manner, when swimming with all their strength from the raft, they must have apprehended a fate at least as terrible as that of being eaten. The raft itself was quite a rude affair, being formed of small bundles of wood lashed together, without any shape or form, quite different from any we had seen before." John Lort Stokes, Journal of a Voyage of Discovery Vol 2 Ch2.1 Natives on a Raft

Not so, however; despite the dreadful fear they appeared to entertain of the white man, maternal affection was strong within them, and risking all to save their offspring, they began to tow the raft with all their strength towards the shore. This devotion on the part of the women to their little ones, was in strong contrast with the utter want of feeling shown by the men towards both mothers and children.

Captain Wickham now, no doubt to their extreme consternation, pulled after the men, and drove them back to the raft. Some dived and tried thus to escape the boat, while others grinned ferociously, and appeared to hope, by dint of hideous grimaces--such as are only suggested even to a savage by the last stage of fear--to terrify the white men from approaching. At length, however, they were all driven back to the raft, which was then towed across the harbour for them; a measure which they only were able to approve of when they had landed, and fear had quite subsided.

Doubtless, the forbearance of our party surprised them, for from their terrified looks and manner, when swimming with all their strength from the raft, they must have apprehended a fate at least as terrible as that of being eaten. The raft itself was quite a rude affair, being formed of small bundles of wood lashed together, without any shape or form, quite different from any we had seen before." John Lort Stokes, Journal of a Voyage of Discovery Vol 2 Ch2.1 Natives on a Raft

The Rivers of the Northern Territory of South Australia

by Captain Carrington late commander SS Palmerston

read to the Royal Geographical Society 1st November 1886

“The natives on the Liverpool were very friendly, and apparently glad to see us ; but very much frightened, or else very shy, as we did not see much of them. We arrived at the head waters of the Tomkinson late one night. At daylight next morning there was a dense fog ; but having taken the bearing of the low hills (Lindsay) on arrival, we walked across the plains to strike them. Suddenly, at about 8 a.m., the fog lifted, and we found we were in the neighborhood of a large number of natives, who all-men, women, and children-came running towards us in the most friendly manner. They appeared very pleased to see us ; and one old man wished to present me with a little girl, probably about six years old, and seemed much disappointed at my non-acceptance. The girl-bright, large-eyed, and intelligent-seemed perfectly willing ; and I am informed it is considered a great honour in the tribes to have a child presented to you. This old man carried a spear with two prongs about 18in. long, made of telegraph or else stout fencing wire. It was a most formidable weapon, and had doubtless been obtained from a great distance. After making the men a present of pipes and tobacco, and distributing a few blankets to the ladies, who certainly needed them, we parted very good friends.” (Capt. Carrington 1884)

by Captain Carrington late commander SS Palmerston

read to the Royal Geographical Society 1st November 1886

“The natives on the Liverpool were very friendly, and apparently glad to see us ; but very much frightened, or else very shy, as we did not see much of them. We arrived at the head waters of the Tomkinson late one night. At daylight next morning there was a dense fog ; but having taken the bearing of the low hills (Lindsay) on arrival, we walked across the plains to strike them. Suddenly, at about 8 a.m., the fog lifted, and we found we were in the neighborhood of a large number of natives, who all-men, women, and children-came running towards us in the most friendly manner. They appeared very pleased to see us ; and one old man wished to present me with a little girl, probably about six years old, and seemed much disappointed at my non-acceptance. The girl-bright, large-eyed, and intelligent-seemed perfectly willing ; and I am informed it is considered a great honour in the tribes to have a child presented to you. This old man carried a spear with two prongs about 18in. long, made of telegraph or else stout fencing wire. It was a most formidable weapon, and had doubtless been obtained from a great distance. After making the men a present of pipes and tobacco, and distributing a few blankets to the ladies, who certainly needed them, we parted very good friends.” (Capt. Carrington 1884)

|

| ||||||||||||