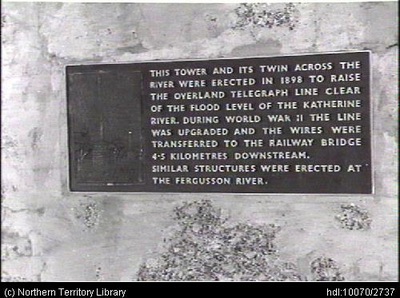

The Overland Telegraph Line & Undersea Cables 1871 & 1879

"No work of greater magnitude or of such vast importance as this knitting of our distant colonies with the rest of our great empire has ever been recorded as having been carried out by one colony without any outside aid whatever." Gladstone

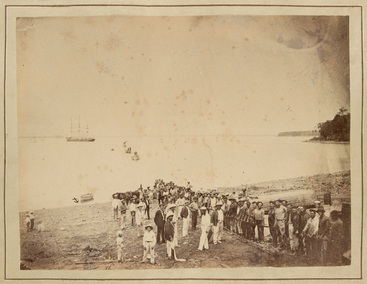

Australia's First International Submarine Cable Landing at Cable Beach - Darwin

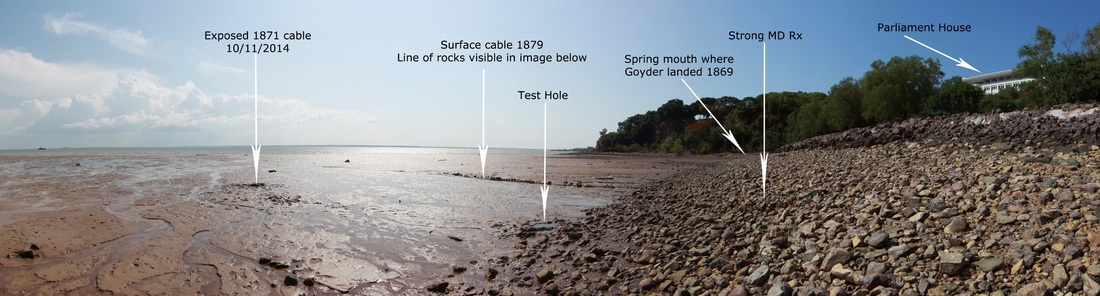

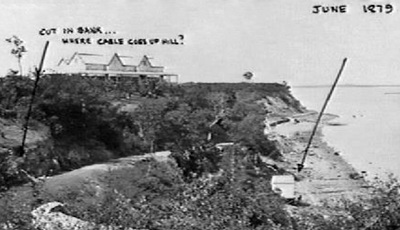

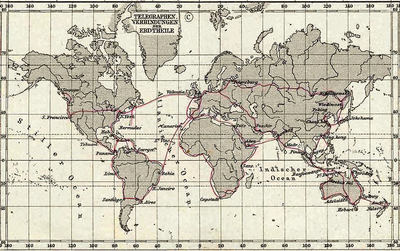

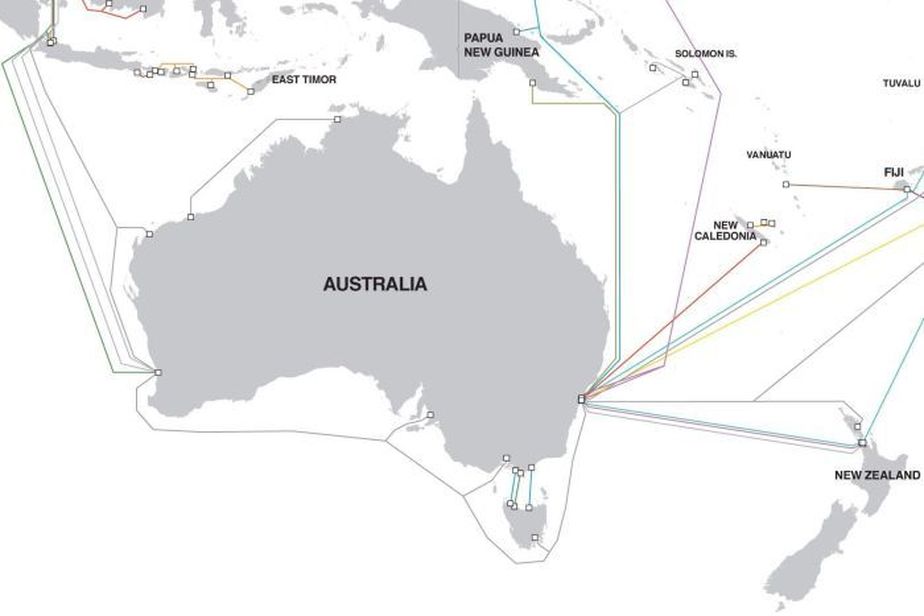

The logic cascade for finding the long lost 1871 undersea cable, by applying a Minelab Metal Detector, was that the first cable runs south of Timor between Darwin to Java and the second (1879) cable runs north of Timor. Given the need to periodically replace the shore ends and occasionally to raise the cable mid-ocean to repair a fault - it would be sensible to ensure that the cables did not cross. Therefore, the visible (1879) cable should run to the north of the original. The new Metal Detector was tested on the visible 1879 cable and with the headphones dropped to around the neck & volume now at near zero, the search began to the south of the visible cable and within 20 paces the target came howling through. It is ideal for metal detectors, being shallow, made of steel and hundreds of miles long - so not a great test for Australia's Minelab machines but it does show that interesting finds can be made in town.

The 1871 cable was lost - the sequence of strong MD responses was recorded by PastMaster Mike Owen using a Minelab Excalibur II on 12/09/2014. A distinctive response similar to that from the later cable visible on the surface - previously identified by Sue Sultana and Rick Weiss. The rock wall beach face is recent reclamation work for a bulk LPG facility. Goyder landed near the spring to the right of picture in 1869.

LANDING THE CABLE by William Brackley Wildey

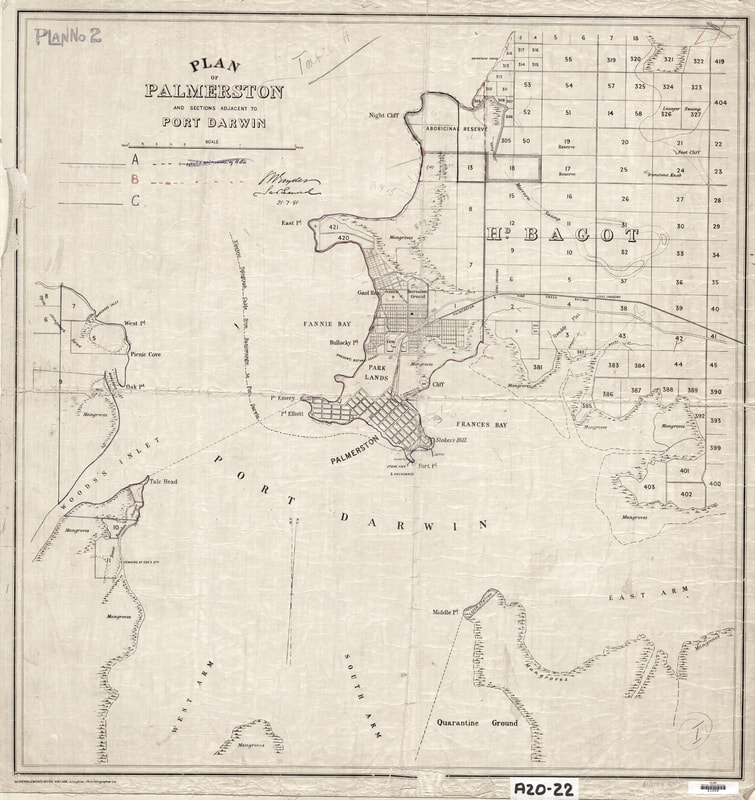

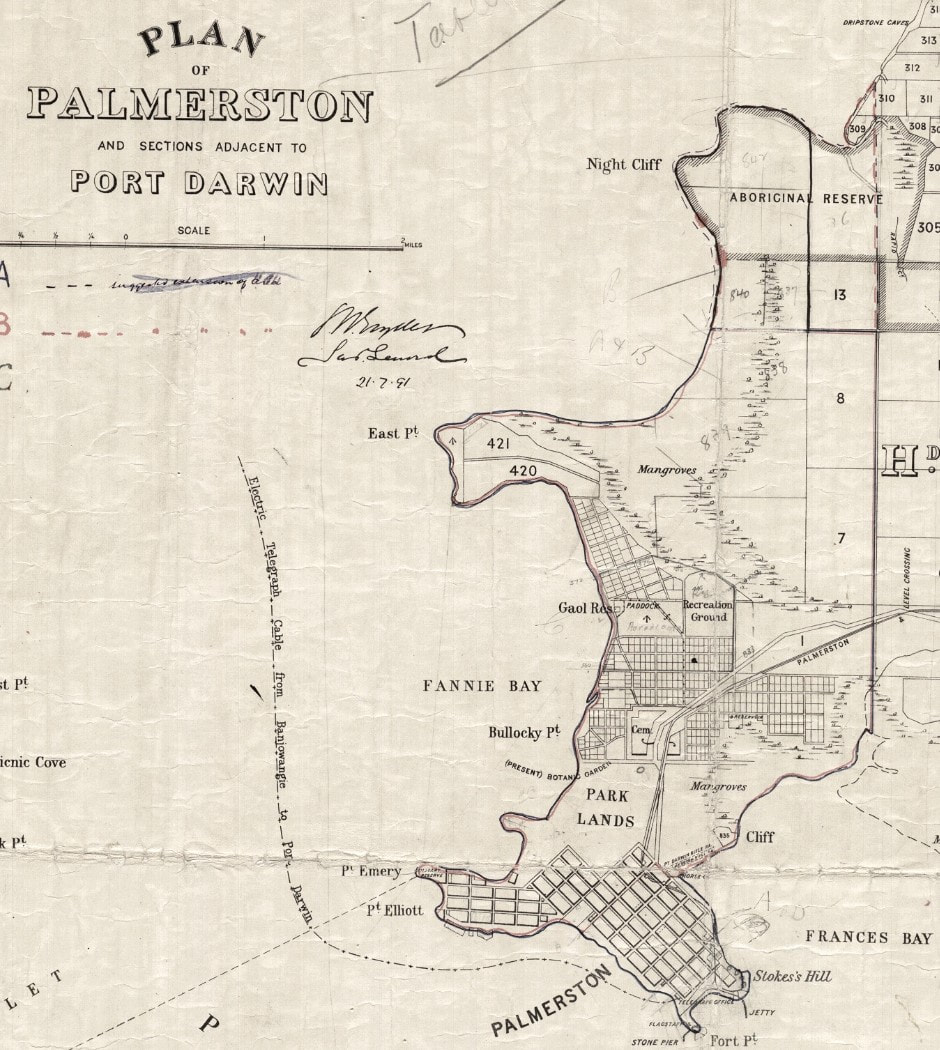

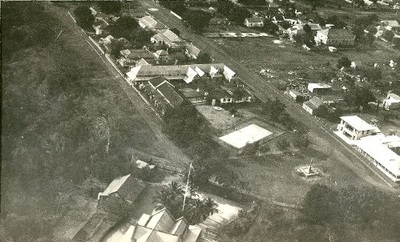

PALMERSTON (Darwin), in latitude south 12° 28' 25", and longitude east 130° 52' 40", is situated about two miles from the heads on elevated table-land. On the beach are the public offices, a row of sheds, constructed of mangrove saplings inserted, upright into the earth, close to each other, roofed with galvanised iron. These are Her Majesty's Custom House, bonded stores, and survey office. The town is arrived at by a steep winding road, to ascend which requires no little exertion; in fact, we saw one new arrival so disgusted with the heat of the sun, and the profuse perspiration he experienced, when half-way up the hill, that he descended and re-embarked on the same vessel that brought him; only having seen the town at a distance. Of such mettle are many who decry the country; but never, by like aid, would England have conquered India, nor would Pizarro's conquest have been effected. The streets are wide and laid out at right angles, north-west and south-east. The principal is Mitchell Street, on the west side of which is the Government House, a large wooden bungalow, most charmingly situated, on a point of land jutting into the bay, having a commanding view of the shipping anchored about 300 yards distant.

A ripple on the surface of the water denotes the course of the cable, as it approaches the spot up the side of the hill, where the shore end, or coil, is deposited in an out-house.

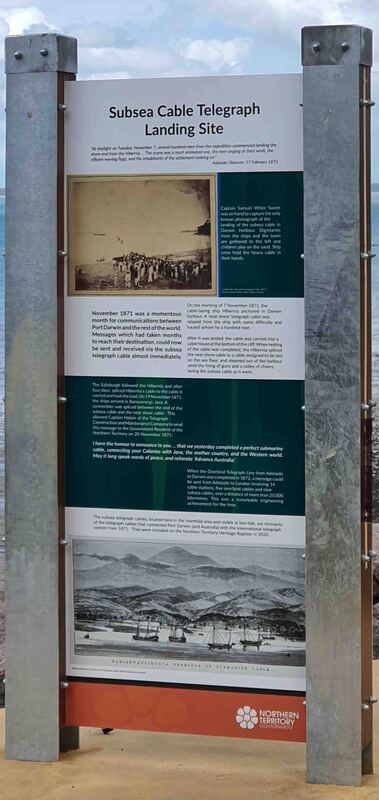

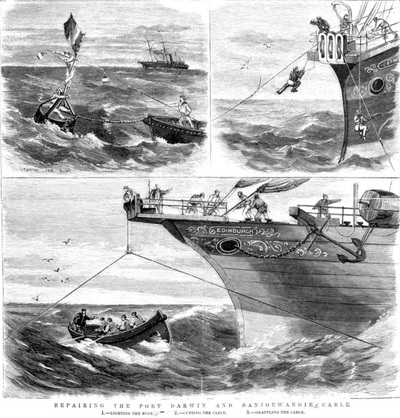

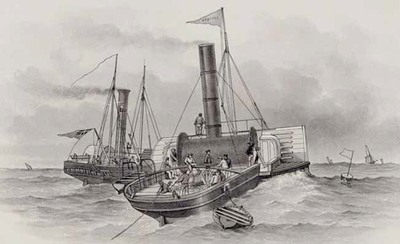

LAYING OF THE CABLE.--The exciting scene of landing the cable, previous to paying it out to Java—the forerunner of a new epoch in the history of Australia—has been thus described: “In October, 1871, the cable expedition arrived. It consisted of the Edinburgh, 2800 tons; the Hibernia, 3100 tons; and the Investigator, 600 tons; Captain Halpin being in command. Messrs. Brown and Stephenson, the electricians for the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, and Messrs. Hockin and Lambert, the electricians of the British-Australian Telegraph Company, and a number of marine engineers and others accompanied the expedition.

A ripple on the surface of the water denotes the course of the cable, as it approaches the spot up the side of the hill, where the shore end, or coil, is deposited in an out-house.

LAYING OF THE CABLE.--The exciting scene of landing the cable, previous to paying it out to Java—the forerunner of a new epoch in the history of Australia—has been thus described: “In October, 1871, the cable expedition arrived. It consisted of the Edinburgh, 2800 tons; the Hibernia, 3100 tons; and the Investigator, 600 tons; Captain Halpin being in command. Messrs. Brown and Stephenson, the electricians for the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, and Messrs. Hockin and Lambert, the electricians of the British-Australian Telegraph Company, and a number of marine engineers and others accompanied the expedition.

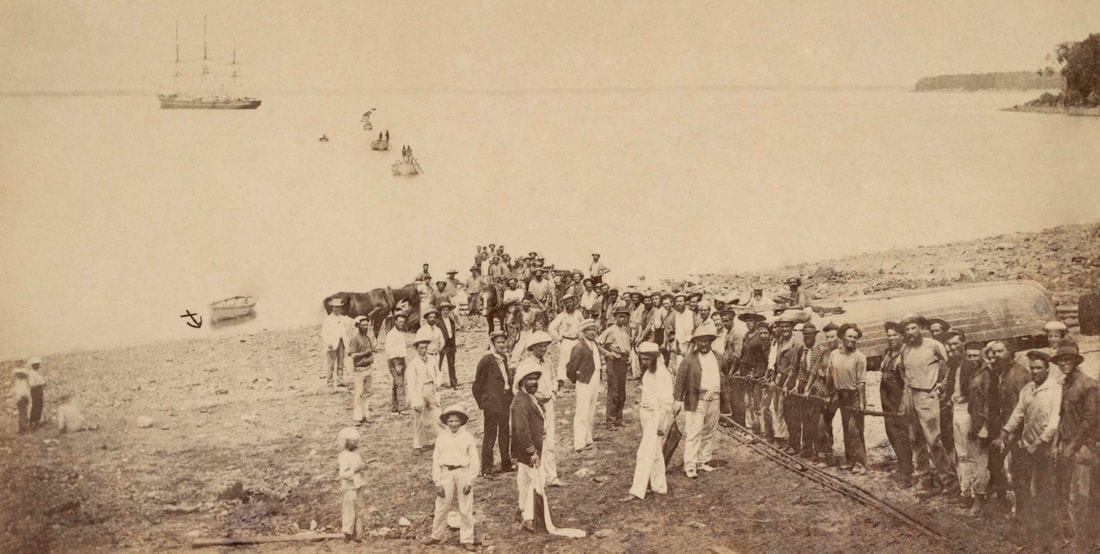

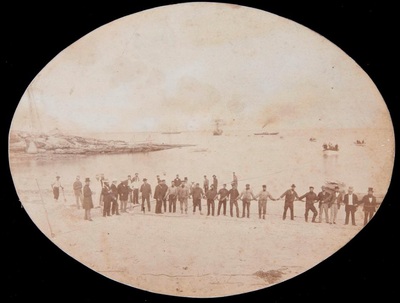

At daylight on Tuesday, 7th November, several hundred men from the expedition commenced landing the shore-end from the Hibernia, distant about half a mile away. The huge cable was carried to the shore in bights held up by boats, the men on shore pulling the end by means of tackle. The scene was a most animated one, the men singing at their work, the officers waving flags, and the inhabitants of the settlement looking on. About nine a.m. the end was landed, carried up a shallow trench on the beach to an iron hut just above high-water mark, and the end joined on to the electrical apparatus all ready, under the charge of Mr. Stephenson; and signals were at once exchanged with the ship. A photograph of the scene was taken, success to the cable and Captain Halpin's health were drunk, and then everybody embarked.

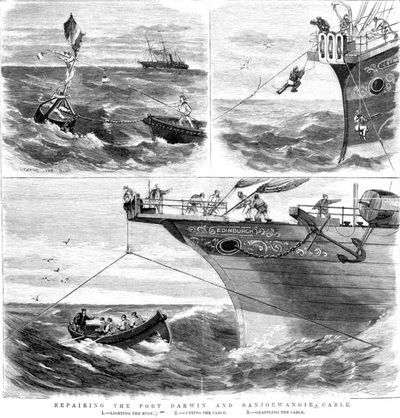

The Hibernia instantly commenced paying out, the Edinburgh immediately steamed after her, and the laying of the Australian cable was fairly commenced, the whole proceedings being carried out with the greatest simplicity and celerity imaginable. Constant testing was kept up night and day by the electrical staffs, both on board and on shore, in case of any faults being in the cable. On the 16th a telegram came through, stating that the expedition had arrived within six miles of Banjoewangi, and that the cable would be cut, and the end sealed up and buoyed until the shore end could be got ready. On the 20th they spoke again, and Captain Halpin announced from Java that the cable was complete and in perfect condition, and that telegraphic communication was established between Australia, the mother country, and the western world.”{History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications http://atlantic-cable.com/Cables/1871Java-PortDarwin/index.htm}

The Hibernia instantly commenced paying out, the Edinburgh immediately steamed after her, and the laying of the Australian cable was fairly commenced, the whole proceedings being carried out with the greatest simplicity and celerity imaginable. Constant testing was kept up night and day by the electrical staffs, both on board and on shore, in case of any faults being in the cable. On the 16th a telegram came through, stating that the expedition had arrived within six miles of Banjoewangi, and that the cable would be cut, and the end sealed up and buoyed until the shore end could be got ready. On the 20th they spoke again, and Captain Halpin announced from Java that the cable was complete and in perfect condition, and that telegraphic communication was established between Australia, the mother country, and the western world.”{History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications http://atlantic-cable.com/Cables/1871Java-PortDarwin/index.htm}

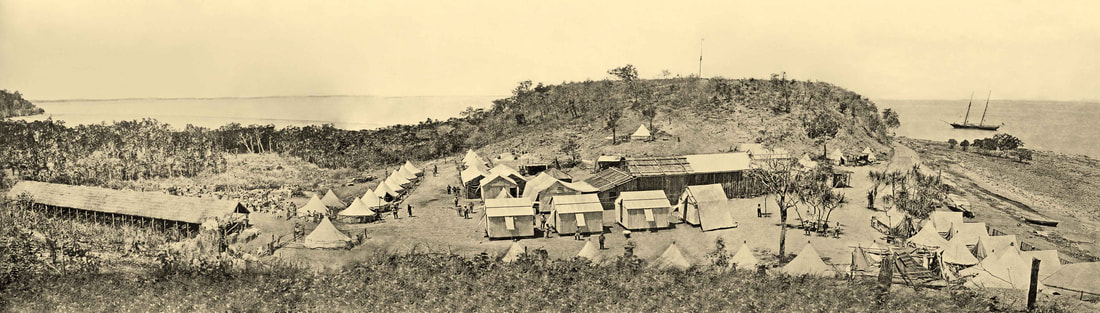

The tide in the image above right is at 0.88 - 2nd headland is Larrakia Naval Base greatly changed as mid-way between the rectangular roof of the boatshed & point is the old bluff. The position from which Sam Sweet took the single iconic image of the landing of the cable seems to have been considerably elevated. Early images show the beachfront to have been modified as wharfage - with the cable being drawn up through a gap for a boat ramp with hard standing - prior to the construction of the jetty at Fort Point.

Telegraph Fleet or Stock Fleet?

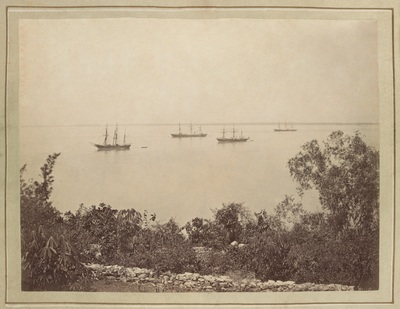

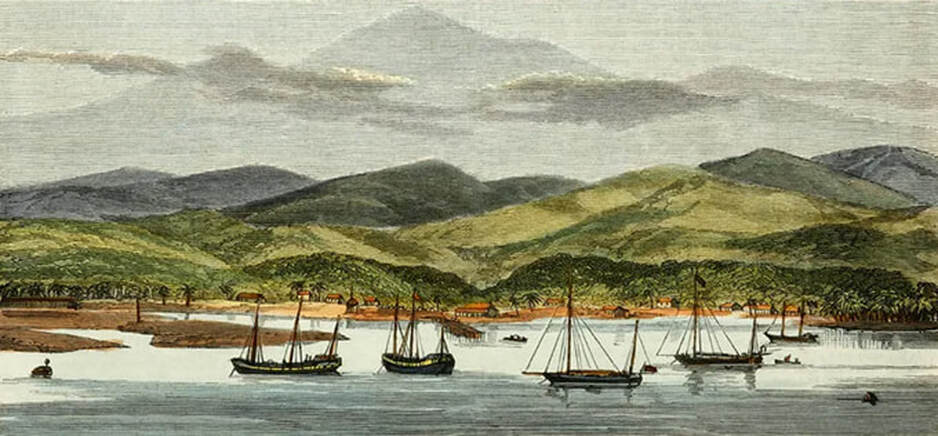

Detail of the iconic image of the day the cable landed at Port Darwin - an arrival up there with Goyder 1869, the Japanese airforce 1942 & Cyclone Tracy 1974.

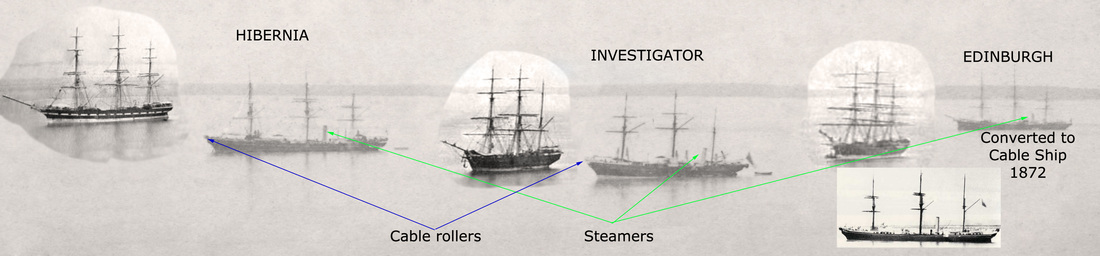

Unfortunately, all three ships have bowsprits & no funnels - so incapable of laying cable. The Government cutter Flying Cloud is at bottom right see image below.

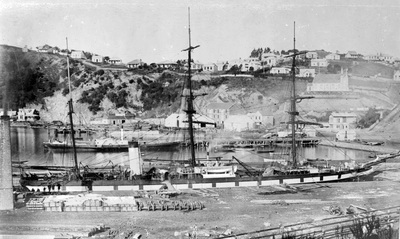

The actual Telegraph Fleet was captured by Capt. Sweet (L>R) just visible behind the Bengal is Gulnare then Hibernia, Investigator & Edinburgh all with steam except Gulnare. Hibernia & Investigator both without bowsprits so converted to cable laying. Edinburgh was converted from a liner to a 4 drum cable ship in 1872.

Seven years earlier the master of Bengal had sold one of her boats to seven desperate men at Escape Cliffs settlement at the mouth of the Adelaide River - they named her The Forlorn Hope & sailed the 24ft open boat 2,500 miles to Geraldton in Western Australia - they sold her to a ship's master who capsized her in the harbour.

Comparison of CS Hibernia, CS Investigator & Edinburgh

The Mystery Ships

State Library Victoria H141662 - Capt. Sweet's anchor motif & 15.

From Residency looking west - Flying Cloud on her Cable (Lameroo) Beach mooring - ships off the cricket ground where war memorial rests today - off lee shore & out of shipping lanes.

State Library Victoria H141662 - Capt. Sweet's anchor motif & 15.

From Residency looking west - Flying Cloud on her Cable (Lameroo) Beach mooring - ships off the cricket ground where war memorial rests today - off lee shore & out of shipping lanes.

Stereoscope photographs had captured Goyder's 1869 survey party at Port Darwin and photography was still a novel & tortuous palaver, especially in the wet tropics in 1871. The mystery ships must have been significant just to warrant a photograph and they are in fact the Stock Fleet, assembled under R.C. Patterson to rescue the Overland Telegraph Line from ignominious default and financial ruin for the young of colony of South Australia. On his sixth attempt, John McDouall Stuart's party had crossed the continent from Adelaide to Chambers Bay (east of Darwin) on 24 July 1862. He was a strong advocate for the NT & the OT line.

The colony was only 27 years old when, on 6th July 1863, Queen Victoria vested South Australia with its Northern Territory by the issue of Letters Patent. The acceptance of the challenge to built the 2,000 mile long Overland Telegraph Line to Darwin, for £120,000 in <18 months, came on the heels of the expensive collapse of their first effort to build the town of Palmerston at Escape Cliffs, at the mouth of the Adelaide River. The second Palmerston (modern Darwin) began with the landing of George Woodruffe Goyder's survey part on 27th December 1868 at Lameroo Beach, aka Cable Beach.

Goyder's party sailed from Adelaide in the barque Moonta and schooner Gulnare under Captain Sweet, who was also deputy to the official photographer Joseph Brooks. Goyder's camp below the bluff of Fort Hill was re-occupied by the advance party of the OT Line in 1870 which also sailed in the Gulnare under Sweet, accompanied by the steamship Omeo, which laid Australia's first submarine telegraph cable between Tasmania and the mainland in July 1859. They joined the first settlers who had arrived at Port Darwin in the 300 ton barque Kohinoor on 1st January 1870 and occupied Goyder's abandoned huts. The 60 men, women & children and a few members of Goyder's original party were castaway pioneers in a desperate struggle to survive. Without the Stock Fleet, the nascent town of Palmerston could not have rescued the starving men of the OT line and the project would have been lost to Queensland. With the defaulter's debt & no telegraph line, the Northern Territory of South Australia was not viable. Eventually the burden of debt forced the SA Government to cede control of the NT to the Federal Government.

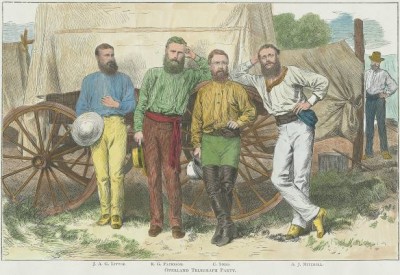

The Stock Fleet

The first pole of the Overland Telegraph Line had been raised at Darwin on 15th September 1870 by the contractors Darwent & Dalwood who had arrived on the Omeo to build the northern section of the line. Unfortunately, they were unaware of the potential for the Roper River to be navigable sufficiently far inland a to supply the bottom end of their section of the line. The work inevitably foundered in the Wet season, rivers were impassable, men and stock were starving. Failure to complete the 300 mile section by the deadline incurred penalties of 5 per cent of the capital raised by the British-Australian Telegraph Company. When the cable came ashore the gap in the incomplete line was filled by a pony-express service and the temporary failure of the submarine cable saved punitive default payments. Darwent & Dalwood's men finally downed tools in despair in May 1871 and were replaced by Patterson the assistant engineer-in-charge of the Overland Telegraph Construction.

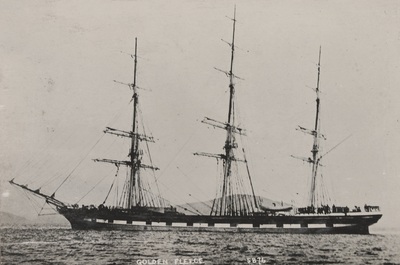

In August 1871, Patterson sailed from Melbourne in the Omeo accompanied by the sailing vessels Golden Fleece 1900 tons; Himalaya 1100 tons; Antipodes 400 tons & Laju 556 tons. They completed loading at Sydney & Newcastle 170 horses, 500 team bullocks, 80 men. The potential of the Roper had still not been fully realised but the Laju loaded with stores made for the extent of navigation in the Roper at Leichhardt's Bar - where he had crossed the river on 19th October 1845 en route for Victoria Settlement at Port Essington. The rest of the Stock Fleet made for Port Darwin. Omeo arriving on 24th August; Antipodes on 6th September; Himalaya & Golden Fleece on 13th September. With no jetty or landing facility at Port Darwin - with poor and often unbroken stock - the trek down the Telegraph Line with empty wagons at 3 miles an hour to pick up the stores at the Roper rapidly descended into a nightmare. On the way to Katherine one third of the bullocks died, many horses collapsed from the head & thirst and then the Wet set in.

In August 1871, Patterson sailed from Melbourne in the Omeo accompanied by the sailing vessels Golden Fleece 1900 tons; Himalaya 1100 tons; Antipodes 400 tons & Laju 556 tons. They completed loading at Sydney & Newcastle 170 horses, 500 team bullocks, 80 men. The potential of the Roper had still not been fully realised but the Laju loaded with stores made for the extent of navigation in the Roper at Leichhardt's Bar - where he had crossed the river on 19th October 1845 en route for Victoria Settlement at Port Essington. The rest of the Stock Fleet made for Port Darwin. Omeo arriving on 24th August; Antipodes on 6th September; Himalaya & Golden Fleece on 13th September. With no jetty or landing facility at Port Darwin - with poor and often unbroken stock - the trek down the Telegraph Line with empty wagons at 3 miles an hour to pick up the stores at the Roper rapidly descended into a nightmare. On the way to Katherine one third of the bullocks died, many horses collapsed from the head & thirst and then the Wet set in.

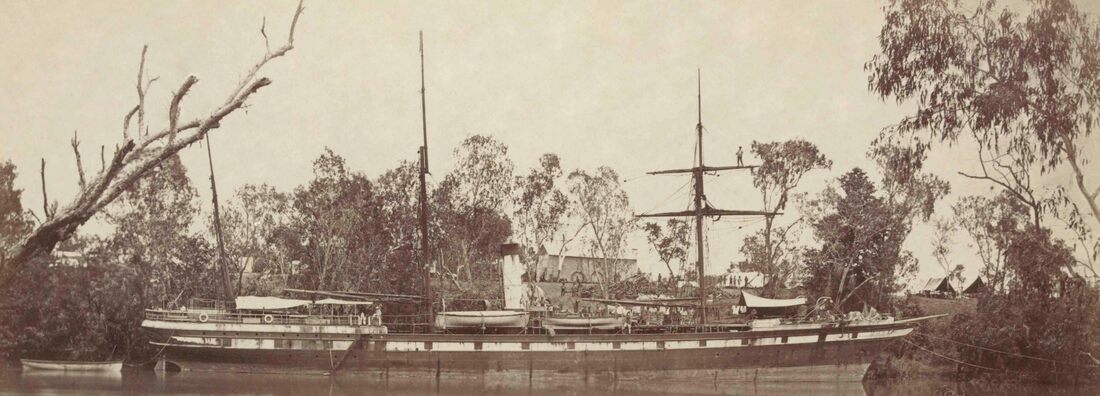

Roper River OT Depot

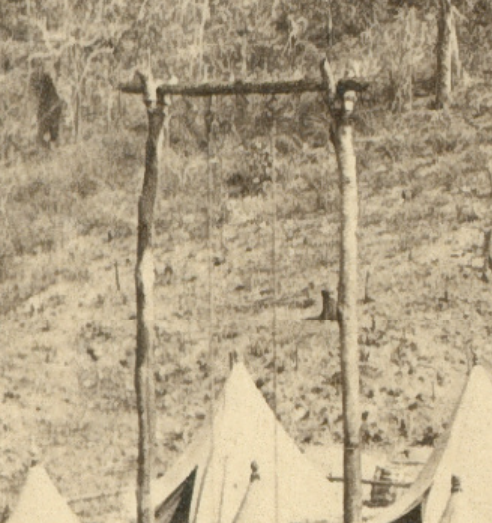

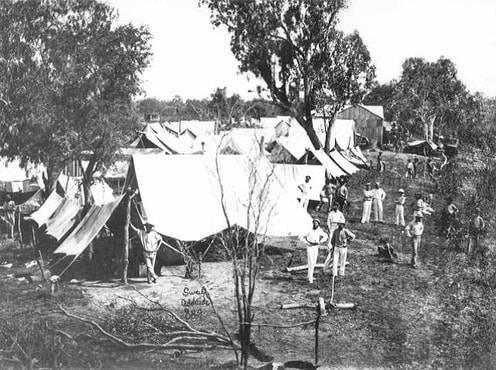

Roper River Depot, 1872. Sweet SLSA (B4635).

Roper River Depot, 1872. Sweet SLSA (B4635).

Captain Cadell first navigated the Roper in 1866 in the paddle steamer Eagle but when the Bengal tried to follow her track in January 1872, bringing stores & equipment to the starving linesmen, she was unable to sail up the swollen river.

Patterson was in charge of building the line between Mataranka & Daly Waters but when he arrived at Leichhardt's Bar on the Roper River he found 3 other line parties already there.

Forty desperate linesmen faced starvation so he ordered them to rig a raft out of a wagon dray & tarpaulins, echoing an earlier horror voyage in a hide & sapling boat by Edmunds & party from the East Alligator to Escape Cliffs on the Adelaide River.

Patterson called the vessel "Elsie' after his wife and rafted 60 miles to the mouth of the river - clawing their way back against the flow with stores for the remainder of the party.

Patterson made an heroic 370 mile wet season ride from Darwin to Leichhardt's Bar where he commandeered a small sailing skiff for the 400 mile trip across the bottom of the Gulf.

At Normanton he used the Queensland telegraph to send an urgent plea for help to Adelaide. Charles Todd sailed from Adelaide aboard the Omeo with 80 horses and stores. The Tararua followed with a further 80 horses and lastly the paddle steamer Young Australian which would be grounded & lost in the Roper near the junction with the Wilton whilst bringing steel poles to replace the wooden ones in 1872. One of her paddle wheels was salvaged by Emerald River missionary Mr Perriman who used it as a waterwheel until a cyclone drove it upstream where it awaits a visit by the PastMasters. (Sources - Trove, Glenville Pike et al below)

Patterson was in charge of building the line between Mataranka & Daly Waters but when he arrived at Leichhardt's Bar on the Roper River he found 3 other line parties already there.

Forty desperate linesmen faced starvation so he ordered them to rig a raft out of a wagon dray & tarpaulins, echoing an earlier horror voyage in a hide & sapling boat by Edmunds & party from the East Alligator to Escape Cliffs on the Adelaide River.

Patterson called the vessel "Elsie' after his wife and rafted 60 miles to the mouth of the river - clawing their way back against the flow with stores for the remainder of the party.

Patterson made an heroic 370 mile wet season ride from Darwin to Leichhardt's Bar where he commandeered a small sailing skiff for the 400 mile trip across the bottom of the Gulf.

At Normanton he used the Queensland telegraph to send an urgent plea for help to Adelaide. Charles Todd sailed from Adelaide aboard the Omeo with 80 horses and stores. The Tararua followed with a further 80 horses and lastly the paddle steamer Young Australian which would be grounded & lost in the Roper near the junction with the Wilton whilst bringing steel poles to replace the wooden ones in 1872. One of her paddle wheels was salvaged by Emerald River missionary Mr Perriman who used it as a waterwheel until a cyclone drove it upstream where it awaits a visit by the PastMasters. (Sources - Trove, Glenville Pike et al below)

Completing the OT Line

|

Charles Todd sent the first message on the completed line from Frew’s Ponds on Thursday, 22 August 1872

“We have this day, within two years, completed a line of communications two thousand miles long through the very centre of Australia, until a few years ago a terra incognita believed to be a desert.” 3600 poles – 3200kms – Contract £128,000 {£40/km} & 2 years {01/01/1871 - 31/12/1872} heavy penalties– 30,000 wrought iron poles x England – 80m apart – repeater stations 250kms apart.

|

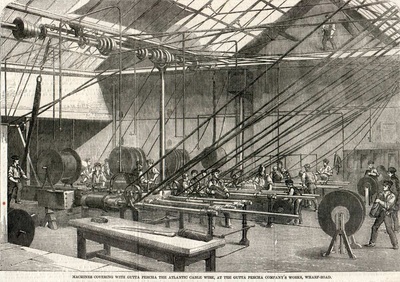

The submarine cables

The conductor of the 1871 cable consists of seven stranded copper wires of about No. 20 B.W. gauge - each surrounded with several layers of gutta percha composition, forming the insulation. This is again encased in armour consisting of iron wires, to protect and give the necessary strength to the cable. This is finally wound with hemp and asphalt. The shore ends of the cable are more heavily protected by very much thicker wires. The main cable, is about l inch in diameter & weighs 3½ tons to the mile while the shore ends weigh about 11½ tons per mile.

The 1879 cable is very similar except that an intermediate size of cable is used, as well as the main and shore cable. The shore end of this cable weighs about 10 tons, the intermediate 3½ and main 1¼ tons per mile.

In this cable, between the gutta percha core & the cable and between the core & the iron wires, brass tape is wound as a protection against the teredo navalis worm that bores through the gutta percha thereby destroying the insulation. These cables cost about £100 per mile. (See 1888 article below)

The 1879 cable is very similar except that an intermediate size of cable is used, as well as the main and shore cable. The shore end of this cable weighs about 10 tons, the intermediate 3½ and main 1¼ tons per mile.

In this cable, between the gutta percha core & the cable and between the core & the iron wires, brass tape is wound as a protection against the teredo navalis worm that bores through the gutta percha thereby destroying the insulation. These cables cost about £100 per mile. (See 1888 article below)

Landing the Cable

“The cable consists of seven small copper wires—a central one, with the six twisted round it. It is insulated by gutta-percha, over this is a coating of tarred hemp, then a sheathing of galvanised iron wire, with an outside covering of tarred hemp. The deep sea portion is three-quarters of an inch in diameter, the intermediate one inch, and the shore ends (twenty miles in length) three inches in diameter.”

Citation: From an article on the 1871 cable landing at Port Darwin -

"Australasia and the Oceanic Region, With Some Notice of New Guinea, From Adelaide-Via Torres Straits-To Port Darwin, Thence Round West Australia" by William Brackley Wildey Published by George Robertson, Melbourne, Sydney, and Adelaide, MDCCCLXXVI (1876) [Thanks to Walter Pearce for this quote & to Bill Burns for the plug.]

Website: https://atlantic-cable.com/Cables/1871Java-PortDarwin/index.htm

Citation: From an article on the 1871 cable landing at Port Darwin -

"Australasia and the Oceanic Region, With Some Notice of New Guinea, From Adelaide-Via Torres Straits-To Port Darwin, Thence Round West Australia" by William Brackley Wildey Published by George Robertson, Melbourne, Sydney, and Adelaide, MDCCCLXXVI (1876) [Thanks to Walter Pearce for this quote & to Bill Burns for the plug.]

Website: https://atlantic-cable.com/Cables/1871Java-PortDarwin/index.htm

Would the replaced shore end be left in situ or recovered and recycled - at 200 tons & costing c £2,000 new perhaps they were raised and refurbished.

150th Anniversary of the 1st cablegram

The minister, NT Administrator and a representative of the Indonesian Embassy in Darwin conjointly unveiled the commemorative panels which feature the only surviving image of 'the landing of the cable' taken by Captain Sam Sweet two weeks before the cablegram arrived from Banjoewangie (Banyuwangy) in Java. Shortly after the Commonwealth took over control of the Northern Territory on 1st January 1901 the name of the town was changed from Palmerston to Darwin resolving years of confusion arising from the address of all telegraphic communications being Port Darwin. The same happened when the Post & Telegraph Office moved from the Telegraph Station at Alice Springs into the town of Stuart.

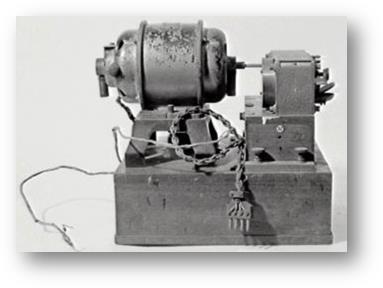

Mystery Cable

Des Fong, the then owner of Aquascene, at Doctor's Gully, had inherited some cable from the previous owner Marshall Peron, who inherited it from Carl Atkinson. It is believed that the cable is part of the Overland Telegraph story. It is not undersea cable, however the men in the image appear to be repairing a similar cable on Cable Beach - or perhaps linking it to the undersea cable via some splitter device.

The cable is encased in a lead tube, there are ten, single strand copper wires, not twisted or paired, each strand is bound in a spiral bandage of 5 parallel strands of silk/cotton. All ten are spiral wrapped in a bandage of woven silk/cotton. There appears to be a powder between the woven bandage and the lead tube. The weave appears too fine for cotton. Paper replaced silk/cotton as an insulator in 1890.

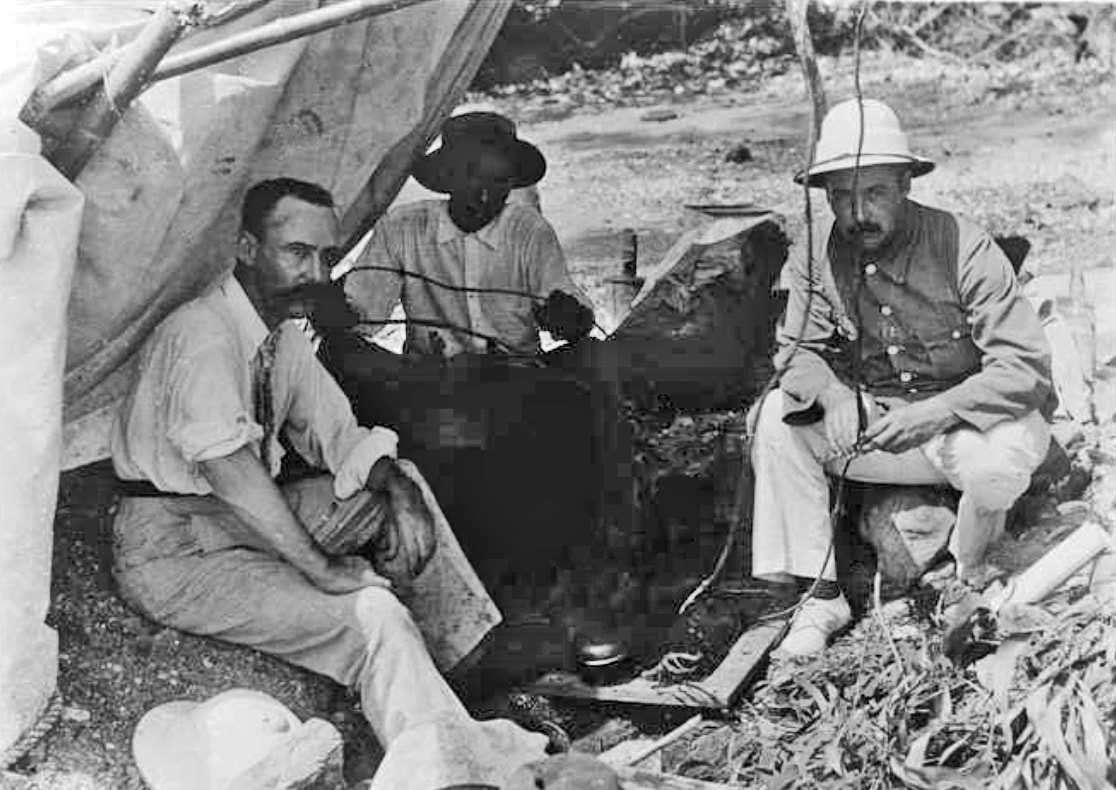

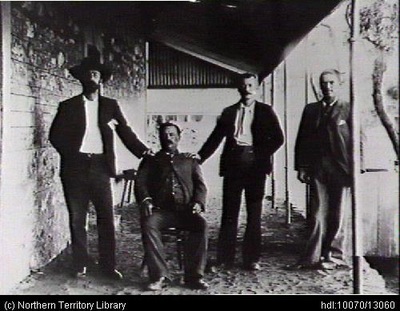

This image at NT Library PH0238-0384 Testing the Cable date unknown - as SL of SA B53805 Cable layers in Darwin ca.1890 - the cable could match the type in question. Did it join the undersea cable in the shack on the beach - was it from the BAT Offices?

The cable is encased in a lead tube, there are ten, single strand copper wires, not twisted or paired, each strand is bound in a spiral bandage of 5 parallel strands of silk/cotton. All ten are spiral wrapped in a bandage of woven silk/cotton. There appears to be a powder between the woven bandage and the lead tube. The weave appears too fine for cotton. Paper replaced silk/cotton as an insulator in 1890.

This image at NT Library PH0238-0384 Testing the Cable date unknown - as SL of SA B53805 Cable layers in Darwin ca.1890 - the cable could match the type in question. Did it join the undersea cable in the shack on the beach - was it from the BAT Offices?

The NTL has the same image (above left) from the Peter Spillett Collection PH0238/0384, undated - Lameroo Beach - "Testing submarine cable under hull of ship on beach." It may have been the hull of the Horsehide Boat but clearly it is not - the number of trees on Fort Hill is interesting.

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

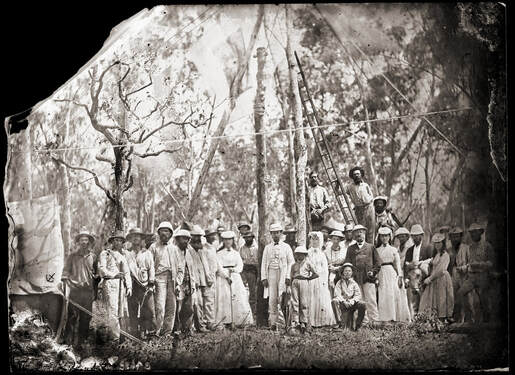

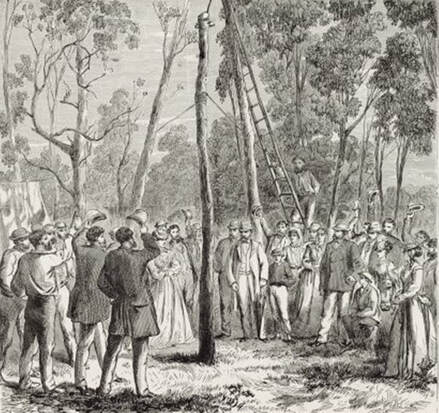

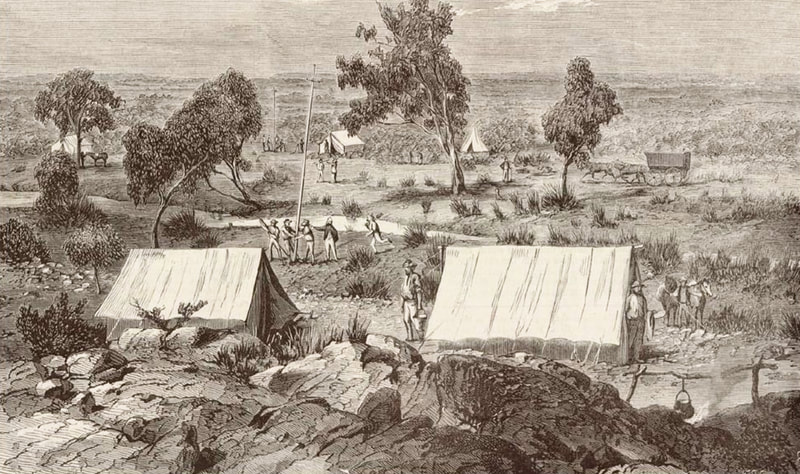

"A group of men, women and children have assembled for the installation of the first pole of the Overland Telegraph on the 15th September, 1870. One of the men is standing on a ladder propped against the pole. [On back of photograph] 'Planting the first pole of the north-south trans continental telegraph line, Port Darwin. / (September 15, 1870. See Hodder, v.2, p. 25.) / For date of commencement of work at Port Darwin see 140/28, page 2 of letter dated 24/3/71.' (Another hand) 'For key to names see p. 22 of S.W. Herbert's MS Reminiscences (Archives 996) Among those present were: Palmer, R.E. Burton, Dr. Furnell (?), Dr. Milner, D.D. Daly, Miss Douglas, W.T. Dalwood, Mrs. W.T. Dalwood, Willie Douglas, A.T. Childs, Mr. Douglas, Captain Douglas, F.W. Dalwood, Miss Douglas, W.U. Paqualin, W. McMinn, Miss B. Douglas, Jas. Darwent, Mason, Fordham, ....Stapleton. (Names from original photo. lent by Miss B. Dalwood)". SLSA

The image at left is merely a group photo as the 'pole' is not in the ground & is beside the tree with the signature bulb in the trunk. In the image at right, which is a printers plate, the tent at left and trees are deep in the background whilst there is distance between the still unburied pole and the tree with the bulb which is itself converted into a telegraph pole - so is planted long before the one with the singed bottom made it into the ground. It was a publicity stunt hastily staged with selected attendees in order to catch the tide. Analysis of the first pole's planting & location are on the accompanying page.......

The Telegraph Stations

Additional Images

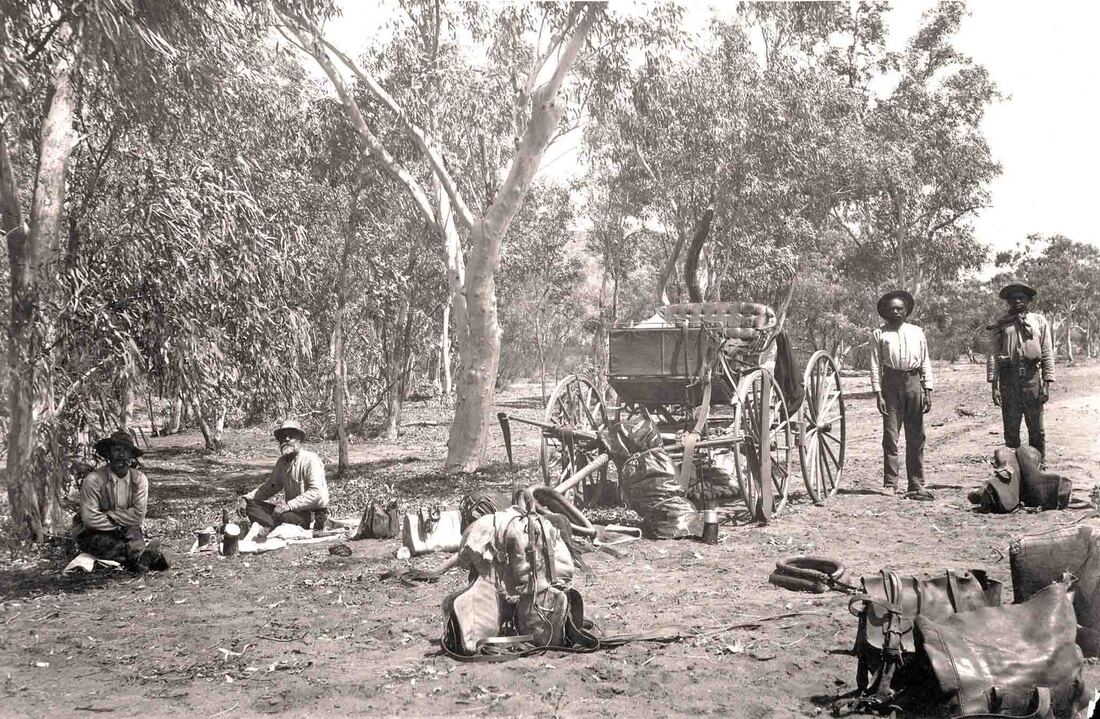

SLSA B22663 Line survey party 1895 NT Collection - The photo was taken during the visit of Lord Kintore's Telegraph Line Survey Party. Mounted Constables Harry Chance and Charles Brookes on the left, and two Aboriginal Troopers at right. The buggy is Lord Kintore's. The expedition travelled along the Overland Telegraph Line in 1891.

Crossed Wires

Ethnographer Arthur Palmer recalls - "Albert Lalka Crowson, already an old man when I first met him in 1977, was a Mudbura stockman who was brought up in the bush with his traditional family before becoming a stockboy and spending the rest of his working life on and around Montejinni, Pigeon Hole and Wave Hill Stations. Over a number of years I spent a lot of time with Albert and two of his brothers, Tobacco Jack Wanamaja and Sugarbag Jayiwa hunting and mapping Mudbura names on the country around Montejinni on the end of the Murranji Track. In the cool of the evening, sitting around a camp fire, Albert would usually relate stories, sometimes for entertainment but often as a means of educating this ‘white boy’.

Those stories, which concerned the early contact days between White settlers and Albert’s family, revealed far more than simple historical notes. He would detail how both sides came to terms with the reality that these changes would demand, although he was always perplexed and regretful that most Whites did not see fit to ‘go company’ with Aboriginals. By this he meant to formalise their working relationship in a business-like manner. Albert reckoned that Aboriginal knowledge of the country and ability to work cattle combined with European management would have been a far more sensible and profitable arrangement right from the start.

Albert related how initially his mother and father could not even conceptually differentiate between rider and horse. That the first explorers and drovers seen riding through the scrub were perceived as one being, a centaur-like supernatural form. Lengthy discussions, after the first contact, were held on how to either deal with or placate the new intruders. Once they were assured that amongst these groups of new beings, there were fairly ordinary, if very different men, then the equation started to narrow down to social and political solutions within their power. Albert told one hilarious story about his father and a group of his mates at a water hole who attempted to address and greet a large, lone scrub bull which had come to drink. The bull responded by scattering everybody up the nearest trees. A little later the group tracked the bull and pin cushioned it with spears. The bull was butchered and eaten on the spot, thereby beginning a long Mudbura association with the cattle industry and also fulfilling the great maxim of cattle country - that is - always eat somebody else’s beef!

Albert described how rapidly Aboriginals adapted and accepted the inevitable changes which White settlement brought. Initially involvement with Whites didn’t necessarily impinge on the independence of Aboriginal groups or individuals. For a long period of time after the initial contact, either by explorers, surveyors or drovers, Aboriginals were very wary of Europeans mainly because they always travelled exclusively as groups of men without women. From an Aboriginal view point, men only travelled into strange territory in the absence of women for the purpose of murder, revenge raids or to kidnap women from another group. Once Europeans started to come through regularly with large mobs of cattle and horses, and it was clear that they could not readily be stopped, Aboriginals started to look closely at what benefits could be gained by association apart from the already rapidly acculturated items such as flour, sugar, tobacco and tea.

Albert’s father’s traditional country had been much farther south in the Mudbura estate when he was a boy and the reason for the move North was told with much mirth. Albert reckons that blackfellas thought that they had the ‘kuddia’ (Whites) sussed out, up until the advent of the overland telegraph line from Alice through to Darwin in the 1870s.

The surveying teams and the building of the line was observed with more than the usual interest. In the absence of better information Albert’s father thought of the telegraph line as a rather unusual fence. A fence with one wire some fifteen feet from the ground on widely spaced posts. The riveting question was; what sort of animal it was meant to contain? Very certainly this animal was extremely tall and without the agility to either duck underneath the wire or the strength to climb over it or break it. With this in mind, and having discovered that the other introduced animals were all fairly harmless herbivores, the size of the new animal was not of any immediate concern, simply a subject of curiosity and unsatisfactory enquiry.

However, the state of alarm was considerably raised when the building teams started erecting the telegraph relay offices. These were stone pill box affairs with purpose built gun slits for warding off hordes of fierce war like and treacherous blackfellas. All the product of bureaucratic concern and over reaction in the far South. Albert’s dad was not burdened with this information. His group reasoned that these fortifications could only be there to protect the ‘shepherds’ at night, or indeed at any other time of the day, from an extremely large and now most certainly carnivorous and fierce new animal that these highly irresponsible Whites were about to introduce. What was going to protect the blackfellas? It was nervously considered very possible that the new animal was being brought in to eat the cattle, which they were only just getting used to. If the Whites were afraid of it, that indicated that this new monster may not be able to distinguish between things it was meant to eat and blackfellas, who it definitely wasn’t supposed to eat.

This is where things became very tricky in the decision making process. The ‘fence’ stretched as straight as a die from horizon to horizon. On which side of the fence was this new beast going to be kept? The ‘shepherd’s’ block houses had gun slits facing in all directions which gave none of the Mudbura any comfort at all. The 50:50 chance of being on the wrong side of the fence were odds far too short. The penalties for being wrong too fearful to contemplate.

To err on the side of caution was rapidly decided upon. As it’s an extremely large continent with plenty of room to move, everybody sensibly decided to quickly and permanently relocate as far away as possible. The embellished stories told by this group to their Northern cousins justifying this move took a lot of living down in later years when the telegraph line monster failed to materialise.

The mass migration by this group of Mudbura saved a large section of the line from one of the great discoveries made by other remaining Aboriginal groups. The insulators, when removed, could be chipped and flaked into superb spear heads and knives. Many share market communications between London and Melbourne were to be rudely interrupted by somebody taking advantage of this newly, evenly distributed, welcome and valuable resource. A lot of these white bifacially flaked spear heads would have found their way into the sides of many a ‘killer’ (any beast killed for immediate consumption) and the occasional careless White man."

Those stories, which concerned the early contact days between White settlers and Albert’s family, revealed far more than simple historical notes. He would detail how both sides came to terms with the reality that these changes would demand, although he was always perplexed and regretful that most Whites did not see fit to ‘go company’ with Aboriginals. By this he meant to formalise their working relationship in a business-like manner. Albert reckoned that Aboriginal knowledge of the country and ability to work cattle combined with European management would have been a far more sensible and profitable arrangement right from the start.

Albert related how initially his mother and father could not even conceptually differentiate between rider and horse. That the first explorers and drovers seen riding through the scrub were perceived as one being, a centaur-like supernatural form. Lengthy discussions, after the first contact, were held on how to either deal with or placate the new intruders. Once they were assured that amongst these groups of new beings, there were fairly ordinary, if very different men, then the equation started to narrow down to social and political solutions within their power. Albert told one hilarious story about his father and a group of his mates at a water hole who attempted to address and greet a large, lone scrub bull which had come to drink. The bull responded by scattering everybody up the nearest trees. A little later the group tracked the bull and pin cushioned it with spears. The bull was butchered and eaten on the spot, thereby beginning a long Mudbura association with the cattle industry and also fulfilling the great maxim of cattle country - that is - always eat somebody else’s beef!

Albert described how rapidly Aboriginals adapted and accepted the inevitable changes which White settlement brought. Initially involvement with Whites didn’t necessarily impinge on the independence of Aboriginal groups or individuals. For a long period of time after the initial contact, either by explorers, surveyors or drovers, Aboriginals were very wary of Europeans mainly because they always travelled exclusively as groups of men without women. From an Aboriginal view point, men only travelled into strange territory in the absence of women for the purpose of murder, revenge raids or to kidnap women from another group. Once Europeans started to come through regularly with large mobs of cattle and horses, and it was clear that they could not readily be stopped, Aboriginals started to look closely at what benefits could be gained by association apart from the already rapidly acculturated items such as flour, sugar, tobacco and tea.

Albert’s father’s traditional country had been much farther south in the Mudbura estate when he was a boy and the reason for the move North was told with much mirth. Albert reckons that blackfellas thought that they had the ‘kuddia’ (Whites) sussed out, up until the advent of the overland telegraph line from Alice through to Darwin in the 1870s.

The surveying teams and the building of the line was observed with more than the usual interest. In the absence of better information Albert’s father thought of the telegraph line as a rather unusual fence. A fence with one wire some fifteen feet from the ground on widely spaced posts. The riveting question was; what sort of animal it was meant to contain? Very certainly this animal was extremely tall and without the agility to either duck underneath the wire or the strength to climb over it or break it. With this in mind, and having discovered that the other introduced animals were all fairly harmless herbivores, the size of the new animal was not of any immediate concern, simply a subject of curiosity and unsatisfactory enquiry.

However, the state of alarm was considerably raised when the building teams started erecting the telegraph relay offices. These were stone pill box affairs with purpose built gun slits for warding off hordes of fierce war like and treacherous blackfellas. All the product of bureaucratic concern and over reaction in the far South. Albert’s dad was not burdened with this information. His group reasoned that these fortifications could only be there to protect the ‘shepherds’ at night, or indeed at any other time of the day, from an extremely large and now most certainly carnivorous and fierce new animal that these highly irresponsible Whites were about to introduce. What was going to protect the blackfellas? It was nervously considered very possible that the new animal was being brought in to eat the cattle, which they were only just getting used to. If the Whites were afraid of it, that indicated that this new monster may not be able to distinguish between things it was meant to eat and blackfellas, who it definitely wasn’t supposed to eat.

This is where things became very tricky in the decision making process. The ‘fence’ stretched as straight as a die from horizon to horizon. On which side of the fence was this new beast going to be kept? The ‘shepherd’s’ block houses had gun slits facing in all directions which gave none of the Mudbura any comfort at all. The 50:50 chance of being on the wrong side of the fence were odds far too short. The penalties for being wrong too fearful to contemplate.

To err on the side of caution was rapidly decided upon. As it’s an extremely large continent with plenty of room to move, everybody sensibly decided to quickly and permanently relocate as far away as possible. The embellished stories told by this group to their Northern cousins justifying this move took a lot of living down in later years when the telegraph line monster failed to materialise.

The mass migration by this group of Mudbura saved a large section of the line from one of the great discoveries made by other remaining Aboriginal groups. The insulators, when removed, could be chipped and flaked into superb spear heads and knives. Many share market communications between London and Melbourne were to be rudely interrupted by somebody taking advantage of this newly, evenly distributed, welcome and valuable resource. A lot of these white bifacially flaked spear heads would have found their way into the sides of many a ‘killer’ (any beast killed for immediate consumption) and the occasional careless White man."