THE MACASSANS

PAGE UNDER VERY SLOW CONSTRUCTION

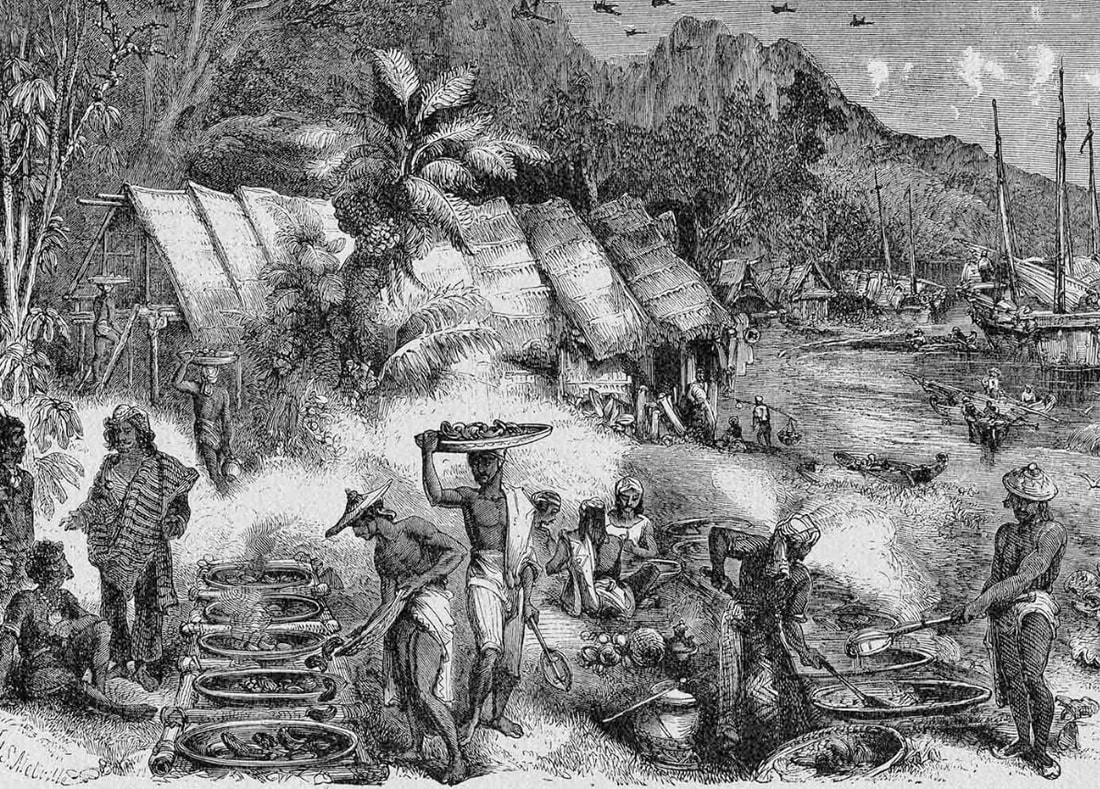

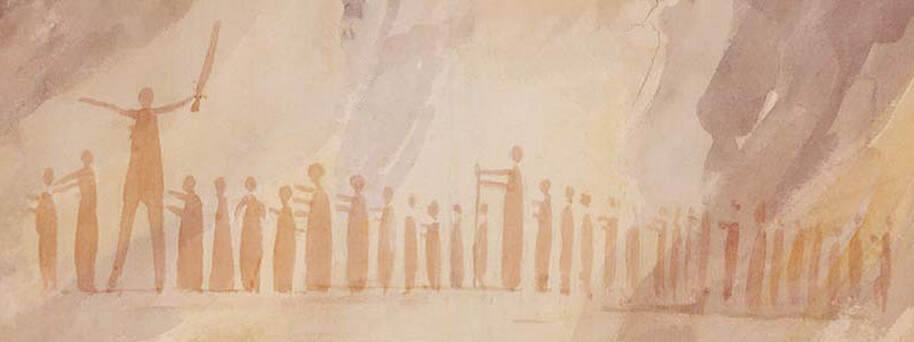

'Reports from European observers, and an outfitter’s contract located by Macknight (1976:20) in South Sulawesi record that Makassans brought with them bamboo and prefabricated wall panels, in a form of kajang and ataps, mats of woven cane and palm leaf from which they constructed their living quarters and smokehouses for curing trepang. '. Whilst the image is fanciful the scheme hcontains the essntial elements of a simple style of processing facility. These images were engraved onto printers plates upon which mountains replace Wet season storm clouds.

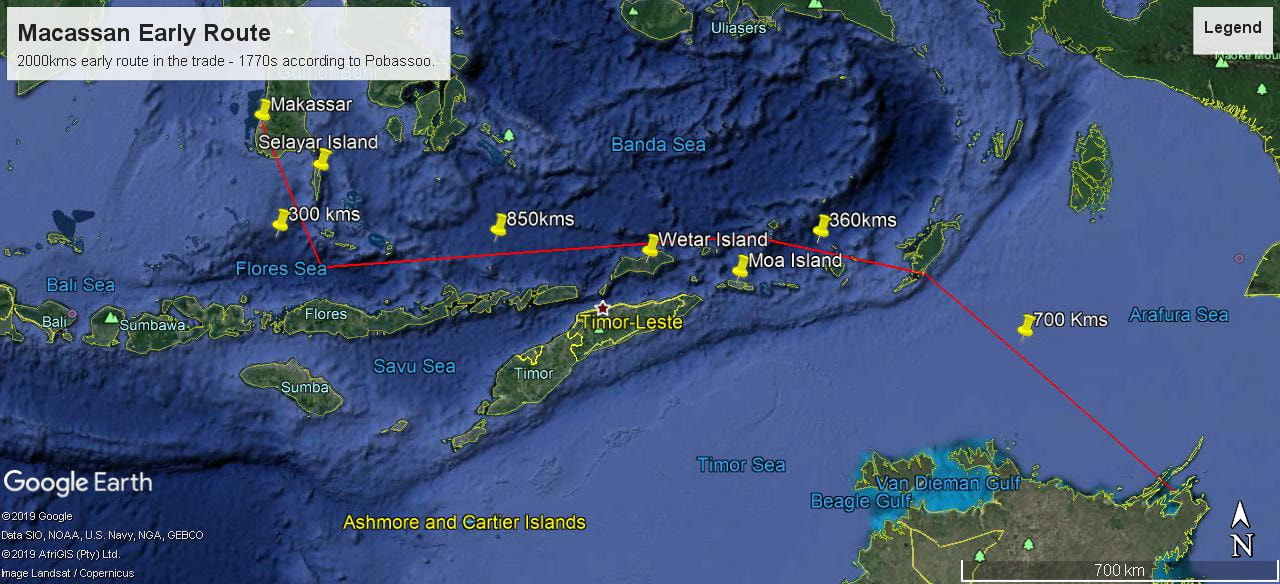

The prau master Pobassoo, who had been speared in the knee, told Matthew Flinders that the voyage took 2 months from Makassar to the Malay Road - a voyage of some 2000kms. The Chinese merchants, who purchased the trepang, were base in the Sumlaki Islands in the south of Jamdena - they subsequently relocated to Makassar which enabled the fleet to transit via Coburg Peninsular - work eastwards into the Gulf then return with some vessels doing a final cure and watering on Melville Island before heading home via a watering point by Palau Jako, at the NE tip of Timor.

The timing of the earliest Asian visits remains an important and controversial debate in the archaeology and history of northern Australia. There are a number of contrasting views relating to the chronology based on documentary and/or archaeological evidence. As mentioned in his chapter (this volume), Macknight (1976, p. 97; 1986, p. 69) initially placed the origins of the Macassan trepang industry between 1650 and 1750 AD. He later revised his evaluation, arguing the industry was not in full swing until the 1780s, with some possible earlier excursions to northern Australia occurring from the 1750s. Macknight’s initial evaluation was based on a number of written sources that date the industry to the eighteenth century, including historical accounts, personal journals and government records, while his re-evaluation (Macknight 2008) is based on evidence presented by Knapp and Sutherland’s (2004) study of detailed trade 1. Understanding the Macassans: A regional approach 3 data for Makassar. At the same time, a number of archaeologists have questioned Macknight’s document-based theory and point to his own archaeological work as evidence for earlier visits. Radiocarbon dates on wood charcoal found in the remains of trepang boiling fireplaces returned dates several hundred years older than ages inferred from documentary evidence. These three geographically separate sites (at Anuru Bay, Entrance Island and Groote Eylandt) returned radiocarbon dates with ages ranging from 1170 to 1520 AD (Macknight 1976, pp. 98–9). Due to the discrepancy between these dates and historical accounts, Macknight argued that there must be a source of error in the archaeological dates. Indeed, Mitchell (1994) argued that the radiocarbon dates were unreliable and that they result from technical problems with radiocarbon analysis of mangrove wood. In addition to the work of Macknight, a pottery shard at Dadirringka rock shelter on Groote Eylandt was found below where a calibrated radiocarbon date of between 904 and 731 BP was obtained (Clarke and Frederick 2011, p. 151). Clarke (1994, 2000) argues that she found further evidence to support earlier contact from an analysis of material excavated at Malmudinga. Importantly, however, Clarke maintains that ‘this initial contact was not necessarily of the order of magnitude of the later trepang industry, organised from the city of Macassar and may have been both sporadic and small scale’ (Clarke 1994, p. 470). Recent rock art and archaeological work undertaken in northwestern Arnhem Land has contributed to the ongoing debate. This includes the radiocarbon dating of a beeswax figure overlaying a painting of a Southeast Asian sailing vessel in the Wellington Range (Taçon et al. 2010; see also Taçon and May, this volume). Results indicate this sailing vessel, most probably a prau, was painted prior to 1664 AD, and there is a 99.7 per cent probability that the overlying beeswax figure was made between 1517 and 1664 AD. Recent archaeological excavations and re-evaluation of earlier excavated materials at the Anuru Bay site have also provided insights into the timing of Macassan visits (Theden-Ringl et al. 2011). The team analysed two skeletons excavated by Macknight in the 1960s and confirmed Macknight’s argument that the skeletons were of Southeast Asian origin (Theden-Ringl et al. 2011, p. 41). They also suggest that one of the individuals died before 1730 AD (Theden-Ringl et al. 2011, p. 45). Overall, we are entering an exciting new era of archaeological research into Macassan sites and new findings will almost certainly rewrite our understanding of the timing and the nature of early Asian contact with Australia. (Understanding the Macassans: A regional approach Marshall Clark and Sally K. May)

Trepang & Tamarinds

Precepts:

Professor Charles Campbell Macknight's 'The Voyage to Marege' is the principal work on Macassans and the trepang trade. Although pitifully little has been done since the fieldwork of the mid-1960's there have been significant contributions by Baker, Wesley et al - a great deal is yet to be learned about the activity of the Macassans prior to what Macknight calls 'the industrial phase'.

Macassans - a useful corruption of Makassar & Makassans to retain the focus of identity whilst recognising Muslim fishermen from a much wider area.

Makassar - Ujung Pandang, on S/W Sulawesi Island, Indonesia - the home port of the trepang fleets & latterly the residence of Chinese merchants who purchased their catch.

When the Portuguese formally established a sandalwood trading colony at Oecussi on Timor in 1515 - they landed on Makassar Beach where they encountered seafaring trepangers from the Bugis/Bone Empire centred upon Sulawesi. Within 50 years the Sandalwood was gone - the Portuguese knew of Australia as the cloud covered coast 3 days sail to the south. It is reasonable to assume that from 1500 the Portuguese were scouting for trade opportunities and aware of Macassar trepangers. Yolngu report that it was the Portuguese who initially brokered the trepang trade with the Chinese and introduced the Macassans to the Marege coast.

It is generally conceded that Macassans may have visited North Australia from the 1650s - perhaps driven south by winds, pirates or simply on spec to gather turtle shell, hardwood timbers, freshwater, pearls and wax.

Industrial Trade: - 1750s accords with the date given by Pobassoo to Flinders & to the appearance of trepang in the records, Chinese cuisine etc.

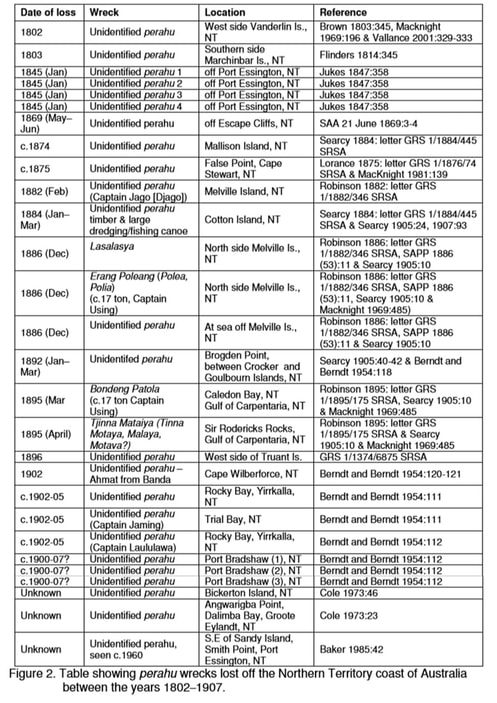

End of Trade:- 1906/7 Season, EO Robinson's Customs Post opposite Croker Island was closed and prau fleet masters obliged to sail into Port Darwin for clearance - as their lateen sails only allowed them to sail downwind they could not leave until the SW monsoon. It was the belated burial of a long dead trade as the fleet numbers & shipwreck losses clearly show. The fleet, from a high of 16 vessels on the NT coast in 1885/6, within a decade it had fallen by 75% and persisted in terminal decline as a family tradition into the opening years of the 20th century (p113).

Protected Sites:- All Aboriginal & Macassan sites are protected under NT Heritage Act. Effectively this is the entire coast from Cape Van Diemen to the Queensland border.

Professor Charles Campbell Macknight's 'The Voyage to Marege' is the principal work on Macassans and the trepang trade. Although pitifully little has been done since the fieldwork of the mid-1960's there have been significant contributions by Baker, Wesley et al - a great deal is yet to be learned about the activity of the Macassans prior to what Macknight calls 'the industrial phase'.

Macassans - a useful corruption of Makassar & Makassans to retain the focus of identity whilst recognising Muslim fishermen from a much wider area.

Makassar - Ujung Pandang, on S/W Sulawesi Island, Indonesia - the home port of the trepang fleets & latterly the residence of Chinese merchants who purchased their catch.

When the Portuguese formally established a sandalwood trading colony at Oecussi on Timor in 1515 - they landed on Makassar Beach where they encountered seafaring trepangers from the Bugis/Bone Empire centred upon Sulawesi. Within 50 years the Sandalwood was gone - the Portuguese knew of Australia as the cloud covered coast 3 days sail to the south. It is reasonable to assume that from 1500 the Portuguese were scouting for trade opportunities and aware of Macassar trepangers. Yolngu report that it was the Portuguese who initially brokered the trepang trade with the Chinese and introduced the Macassans to the Marege coast.

It is generally conceded that Macassans may have visited North Australia from the 1650s - perhaps driven south by winds, pirates or simply on spec to gather turtle shell, hardwood timbers, freshwater, pearls and wax.

Industrial Trade: - 1750s accords with the date given by Pobassoo to Flinders & to the appearance of trepang in the records, Chinese cuisine etc.

End of Trade:- 1906/7 Season, EO Robinson's Customs Post opposite Croker Island was closed and prau fleet masters obliged to sail into Port Darwin for clearance - as their lateen sails only allowed them to sail downwind they could not leave until the SW monsoon. It was the belated burial of a long dead trade as the fleet numbers & shipwreck losses clearly show. The fleet, from a high of 16 vessels on the NT coast in 1885/6, within a decade it had fallen by 75% and persisted in terminal decline as a family tradition into the opening years of the 20th century (p113).

Protected Sites:- All Aboriginal & Macassan sites are protected under NT Heritage Act. Effectively this is the entire coast from Cape Van Diemen to the Queensland border.

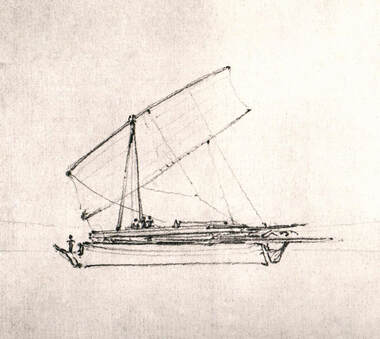

JL Stokes at Timor

Our Swan River native came up to me after we had anchored, dressed in his best, shoes polished, and buttoned up to the chin in an old uniform jacket. "Look," said he, pointing to some Malay lads alongside in a canoe, "trousers no got 'um." A toss of the head supplied what was wanting to the completeness of this speech, and said as plainly as words could have done, "poor wretches!" I tried in vain to point out their superiority, by saying, "Malay boy, work, have house; Swan River boy, no work, bush walk." I then drew his attention to the country, the delicious fruits and other good things to eat (knowing that the surest road to an Australian's heart is through his mouth) but all was in vain! my simple friend shook his head, saying, "No good, stone, rock big fella, too much, can't walk." Home, after all, is home all the world over, and the dull arid shores of Australia were more beautiful in the eyes of this savage than the romantic scenery of Timor, which excited in him neither wonder not delight. It was amusing to see how frightened he was on going ashore the first time. With difficulty could he be kept from treading on our heels, always, I suppose, being in the habit, in his own country, of finding strangers to be enemies. He was instantly recognised by the Malays, who had occasionally seen natives of Australia returning with the Macassar proas from the north coast, as a marega,* much to his annoyance.

(*Footnote. I have never been able to learn the meaning of this word. They told us at Coepang it signified man-eater; which explains the native's annoyance; and may serve as a clue to the discovery that the aborigines of the northern part of the continent occasionally eat human bodies as they do in the south.) [Discoveries in Australia Vol 2 by J. Lort Stokes.]

(*Footnote. I have never been able to learn the meaning of this word. They told us at Coepang it signified man-eater; which explains the native's annoyance; and may serve as a clue to the discovery that the aborigines of the northern part of the continent occasionally eat human bodies as they do in the south.) [Discoveries in Australia Vol 2 by J. Lort Stokes.]

Tamarinds

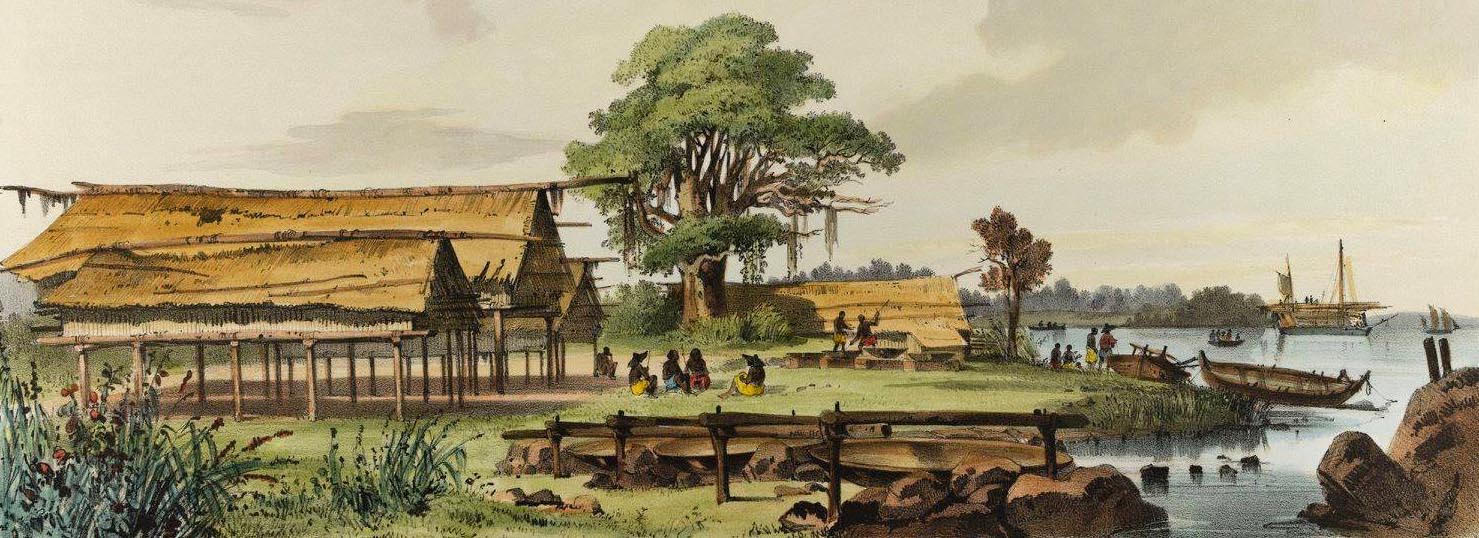

Dumont d'Urville visited Raffles Bay in the corvettes Astrolabe and Zelee between 27 March and 6 April 1839

The prefabricated smoke houses were constructed in sections at Makassar. The antiquity of the Tamarind suggest an age of many centuries in 1839. The two different styles of vessel is interesting as the clinker built one has a broad beam & the other is a rowing boat. Two sorts of stonelines are shown, in the foreground the beams rest on uprights & swing over the cauldrons presumably to assist in emptying them.

Rock Art

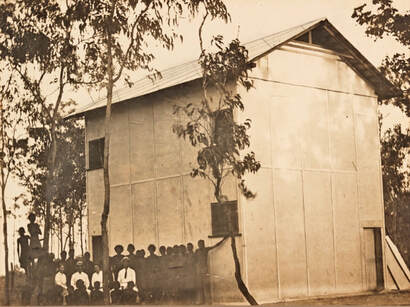

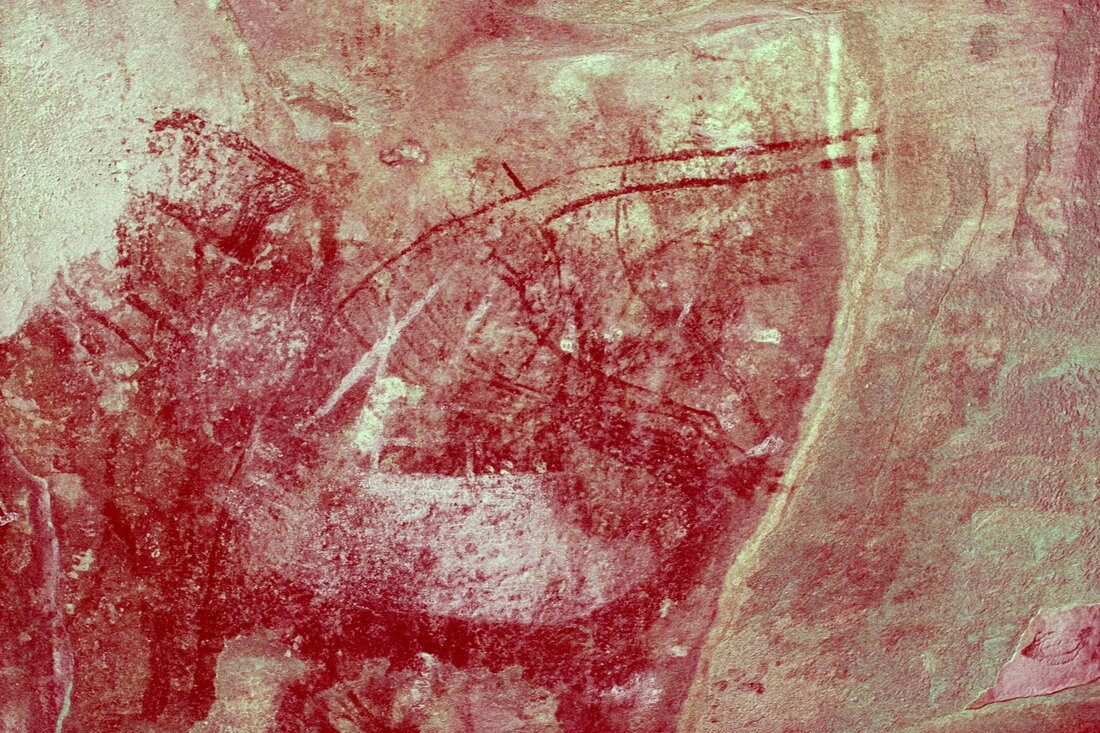

At left a building with a box gable roof, possibly of two stories, vertical structural elements and either panels or decoration. Suggestion of a Macassan Smokehouse - Macknight & George Chaloupka 1993, 1996

The image at right is the first building at the South Goulburn Island Mission which is extant in frame and within 20 miles of the rock art site in the Wellington Range. This building should be heritage listed and repaired.

The image at right is the first building at the South Goulburn Island Mission which is extant in frame and within 20 miles of the rock art site in the Wellington Range. This building should be heritage listed and repaired.

Beach erosion here is extreme as the ground is sand and gravel - a fish trap is now so far from the shore it is thought to be some form of aquaculture. The tamarind on the cliff that hosted morning tea for the clinic staff in the 1970 & early 80's has long since been claimed by the sea. This erosion will soon claim the road below the old clinic and threaten the buildings.

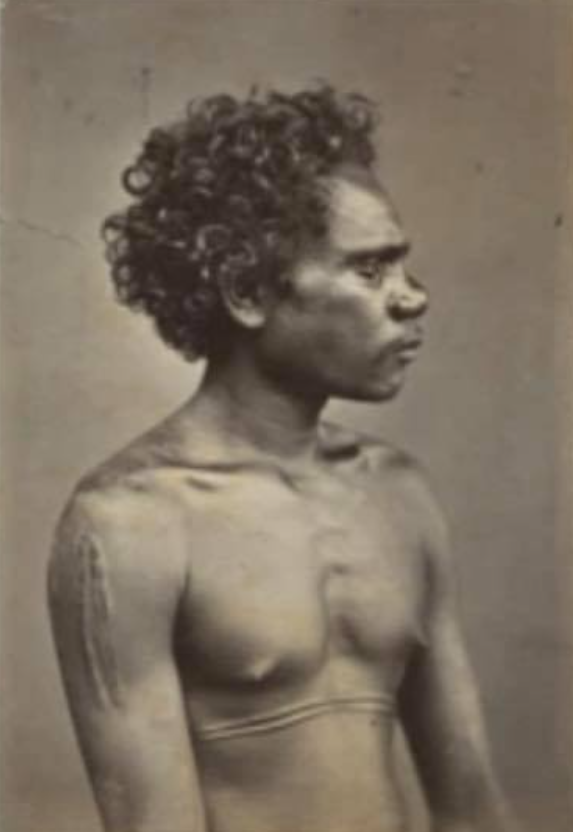

Macassan Anchors

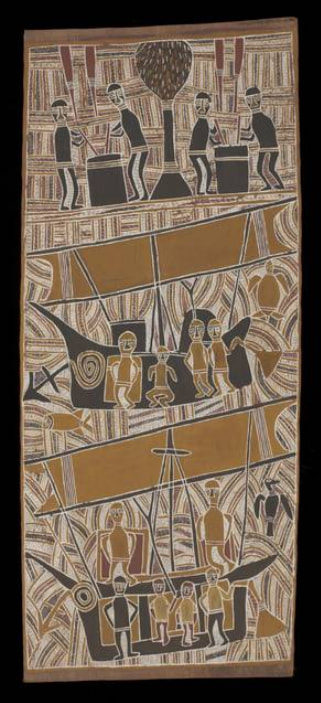

From "Art in Arnhem Land " [1950] by Elkin, Berndt and Berndt.

The top object is described as a Macassan anchor - the one below it, with one prong, is the Baijini anchor.

They are both under a heading 'Love Magic Objects'. [Plate 19a]

The top object is described as a Macassan anchor - the one below it, with one prong, is the Baijini anchor.

They are both under a heading 'Love Magic Objects'. [Plate 19a]

Chasm Island - Groote Eylandt Archipelago

Depicted are four parallel lines of paddlers being two lines on either side of a double outrigger canoe - led by a figure with a woomera in the front centre position. If the stroke waved a sword to conduct the paddlers then a woomera would be a good harmonic as are yam sticks for paddles. The dance is performed in mortuary ceremonies by the Warramirri people of NE Arnhemland.

D'Stretch of PastMasters' image from the Wessel Islands

D'Stretch of PastMasters' image from the Wessel Islands

Matthew Flinders 'Voyage to Terra Australis'. "In the deep sides of the chasms were deep holes or caverns undermining the cliffs; upon the walls of which I found rude drawings, made with charcoal and something like red paint upon the white ground of the rock. These drawings represented porpoises, turtle, kanguroos and a human hand; and Mr. Westall, who went afterwards to see them, found the representation of a kanguroo , with a file of thirty-two persons following after it. The third person of the band was twice the height of the others, and held in his hand something resembling the whaddie, or wooden sword of the natives of Port Jackson; and was probably intended to represent a chief."

Perhaps the charcoal was manganese - of which Searcy reported finding stockpiles ready for export on a Macassan site in Melville Bay but could not discover its purpose. It is now understood that the sword carried by the Stroke is a woomera, commonly carried by senior men during times of ceremony and the two double lines of eight figures with yam sticks represent the paddlers. The dancers represent the crew of a large SE Asian ocean-going auxiliary vessel - utilising both sail and paddle power - with two banks of eight rowers on each side of the vessel as depicted in this D'Stretch version of a rock art image found by the PastMasters in the Wessel Islands in 2013.

Perhaps the charcoal was manganese - of which Searcy reported finding stockpiles ready for export on a Macassan site in Melville Bay but could not discover its purpose. It is now understood that the sword carried by the Stroke is a woomera, commonly carried by senior men during times of ceremony and the two double lines of eight figures with yam sticks represent the paddlers. The dancers represent the crew of a large SE Asian ocean-going auxiliary vessel - utilising both sail and paddle power - with two banks of eight rowers on each side of the vessel as depicted in this D'Stretch version of a rock art image found by the PastMasters in the Wessel Islands in 2013.

Port Essington

This image is of course staged and Foelsche even dressed up some of this vessel's crew but nevertheless it fairly represents the elements of the once familiar Macassan site with Smokehouse, palisaded compound and Aboriginal humpies.

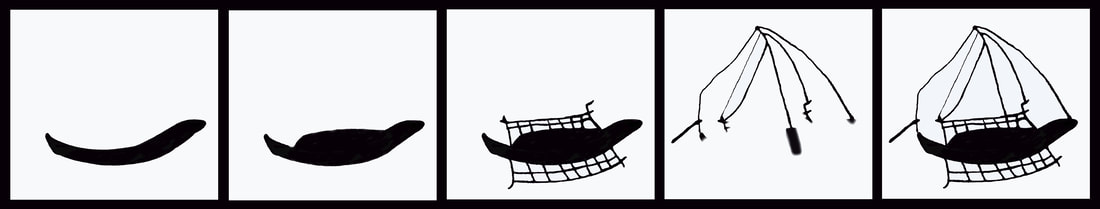

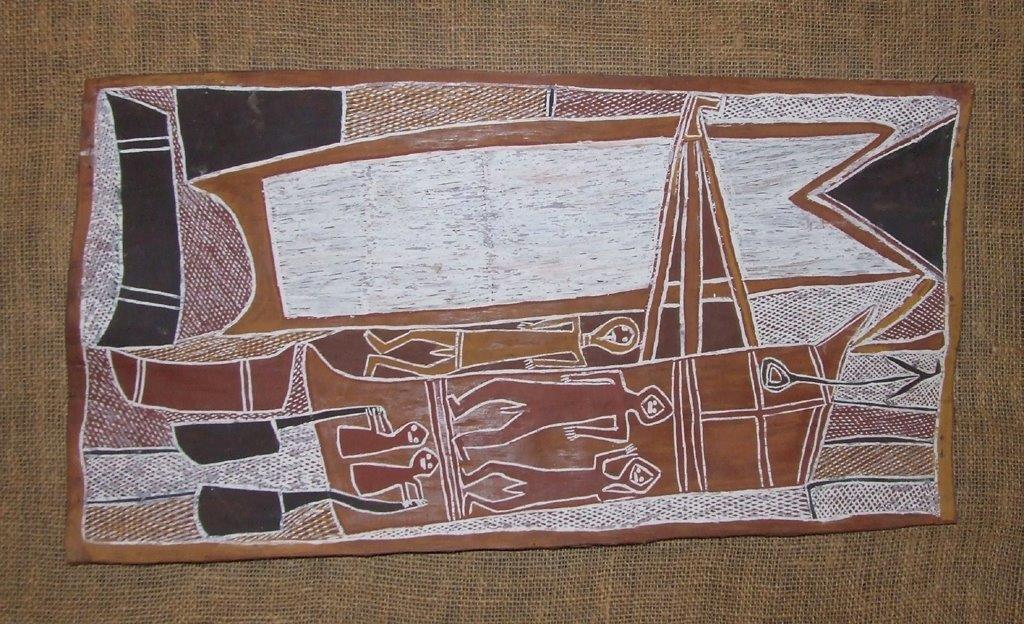

Types of Prau

PRAUS IN MAREGE: MAKASSAN SUBJECTS IN ABORIGINAL ROCK ART OF ARNHEM LAND, NORTHERN TERRITORY, AUSTRALIA

GEORGE CHALOUPKA

Anthropologie (1962-)

Vol. 34, No. 1/2 (1996), pp. 131-142 (12 pages)

Published By: Moravian Museum

GEORGE CHALOUPKA

Anthropologie (1962-)

Vol. 34, No. 1/2 (1996), pp. 131-142 (12 pages)

Published By: Moravian Museum

Trepang Processing Sites - Elements & Variations

Anecdotes

One of the great stories of the Macassan era (1780-1907) concerns the extraordinary actions and bravery of Liyagawumirr men Gayalumpu and Gayasati, who refused to be chased from their land by Macassans who were seeking revenge for the killing of trepangers in the Cadell Strait. This happened in the mid to late 1800s. In one account, the Macassans had interfered with ceremonial regalia near Wurrpan (Emu) and Yolngu retaliation was swift. The entire crew of one of the praus was killed and a hole was smashed through the hull, sinking the craft. The head of the Macassan fleet was intent on killing all the Yolngu at Galiwin’ku or, at the very least, driving them from their land. He ordered an armed execution squad to the shore, near what was described as the Macassan ‘castle’ on the main beach of today’s settlement. But Gayalumpu and Gayasati stood firm. They buried themselves up to their waists in the sand in defiance of the Macassans and argued their innocence in the Malay language. It was the Macassans who had violated the agreement that gave them access to Yolngu land. The fleet leader, impressed by the courage of these two Yolngu men, called off the attack, and took them as prisoners to Makassar for several years. In the 1980s, this story was told with great pride in the Yolngu culture classes at Shepherdson College, Elcho Island, but is less well known today. [IM FB post 12/July 2021]

n.b. These appear to be the Macassan names of the Yolngu leaders. It was very common for such names to be bestowed upon elders working in close cooperation with the trepangers. Their Yolngu names are unknown. [IM]

n.b. These appear to be the Macassan names of the Yolngu leaders. It was very common for such names to be bestowed upon elders working in close cooperation with the trepangers. Their Yolngu names are unknown. [IM]

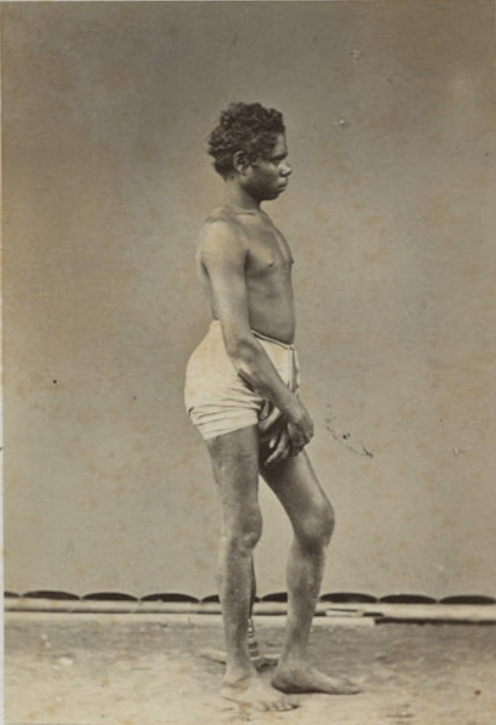

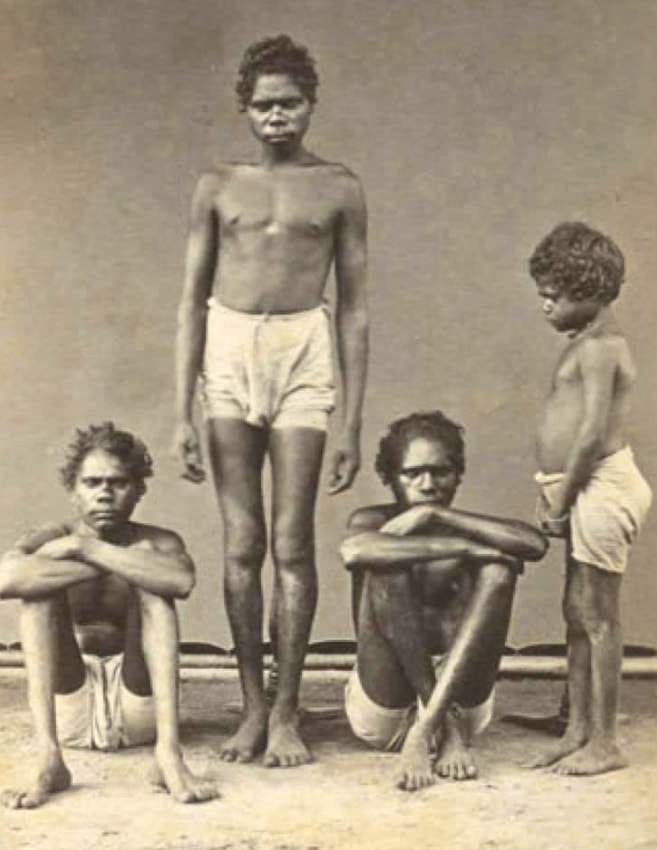

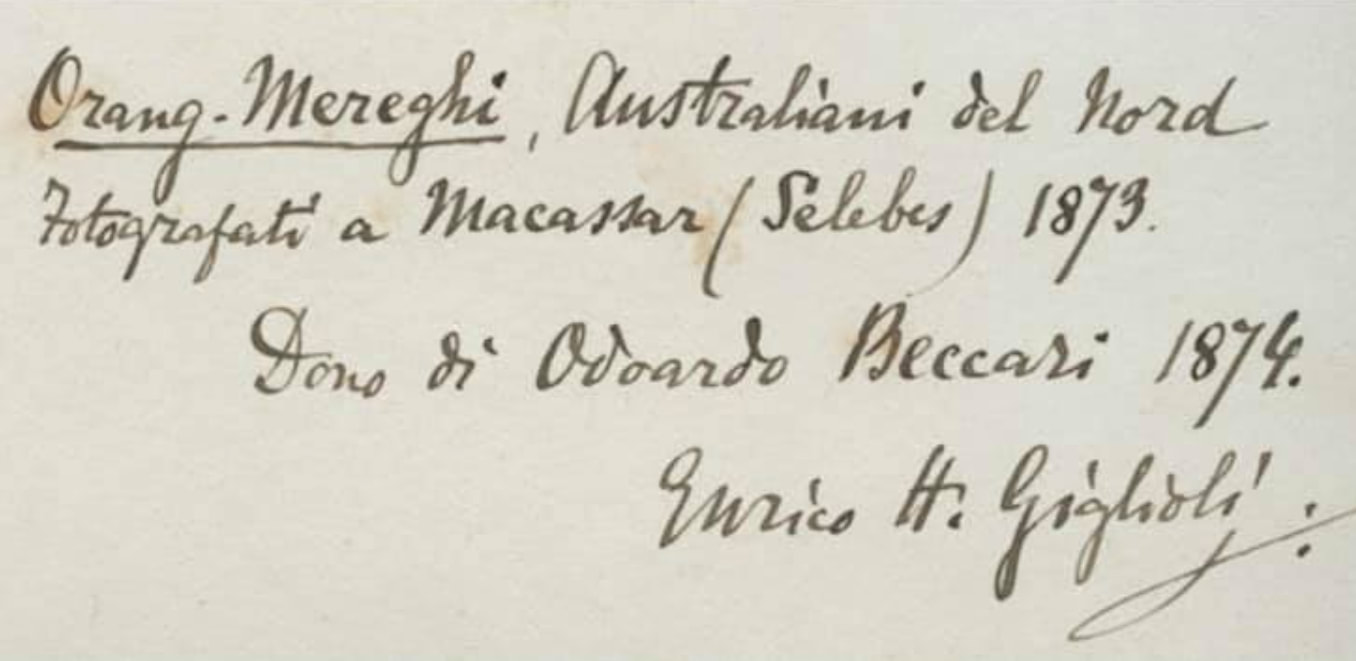

Arnhemlanders in Makassar

Much interest was shown in the stories of Yolngu living in Makassar during the trepang era (1780-1907). While the extended account of Wangurri elder Djalatjirri from his 1895 trip describes various NE Arnhem men and women who had married Indonesians and raised large families in Makassar, we only have a handful of names of those many others who left Australian shores and never returned. These extraordinary photographs of ‘Orang Mereghi’ (People of Australia’s Top End or Marege – Australiani del Nord), were taken in 1873 in a studio in Makassar. Extremely rare, these images are now held in a museum in Rome, Italy, in the collection of the famous zoologist and anthropologist Enrico Hillyer Giglioli (1845-1909). No names are recorded in the caption for either the young adult, the three teenage boys, or the Aboriginal child. Jane Lydon’s chapter in ‘Picturing Macassan–Australian Histories’, suggests that the man is a Bininj from the Cobourg Peninsula, but there is no information for the others. We had not heard of such young children being taken to Makassar, and we wonder what sort of scenarios led to his transportation, and what became of him. What became of them all?

IM observed that all the Aboriginal people living in Makassar around 1910 were supposed to have been repatriated, about 80 of them, but there’s no record that anyone ever returned. More likely they were dropped in north Queensland or sold into slavery somewhere. Many did not wish to return, having married a Macassan or Papuan wife there.

Sources & Resources

|

Macassans and their pots in northern Australia

Citation - Bulbeck, F & Rowley, B 2001, 'Macassans and their pots in northern Australia', in C. Frederickson I. Wolters (ed.), Altered States: Material Culture and Shifting Contexts in the Arafura Region, Northern Territory University Press, Darwin, pp. 55-74. Year 2001 ANU Authors Dr Francis Bulbeck Field of Research •Pacific History (Excl. New Zealand And Maori) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||

Macknight

Campbell Macknight's 'Voyage to Marege' (attached thesis) is the foundation work of Macassan studies. His thesis 'The Macassans - A study of the early trepang industry along the Northern Territory Coast' was published as an engaging and accessible volume 'The Voyage to Marege'. The NT fieldwork for his thesis was conducted in the mid-1960s and he continues to publish in related fields. The link below lists his published papers. A search of the ANU site for 'Macassan' yields papers by noted researchers including our Daryl Wesley whose rock art and Anuru Bay works are highly regarded.

|

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||

Mackintosh

Ian McIntosh has publish many works dealing with the relationship between East Arnhemland aboriginal people and the successive visitors to the coast whose activities inspire much of the language, oral history and cultural tradition.

|

| ||||||||||||

Wesley

Daryl Wesley of Flinders University has done considerable throughout Arnhemland - notably at Anuru Bay and the Wellington Ranges - and his rock art research continues to expand our knowledge of this cultural tradition.

|

| ||||||||||||

n.b. Brady ANU - Macc Pipes, Grog etc - same as opium pipes because the longer the pipe the cooler the smoke - handy for bad baccy & beach vine.