EYAM - The Plague Days

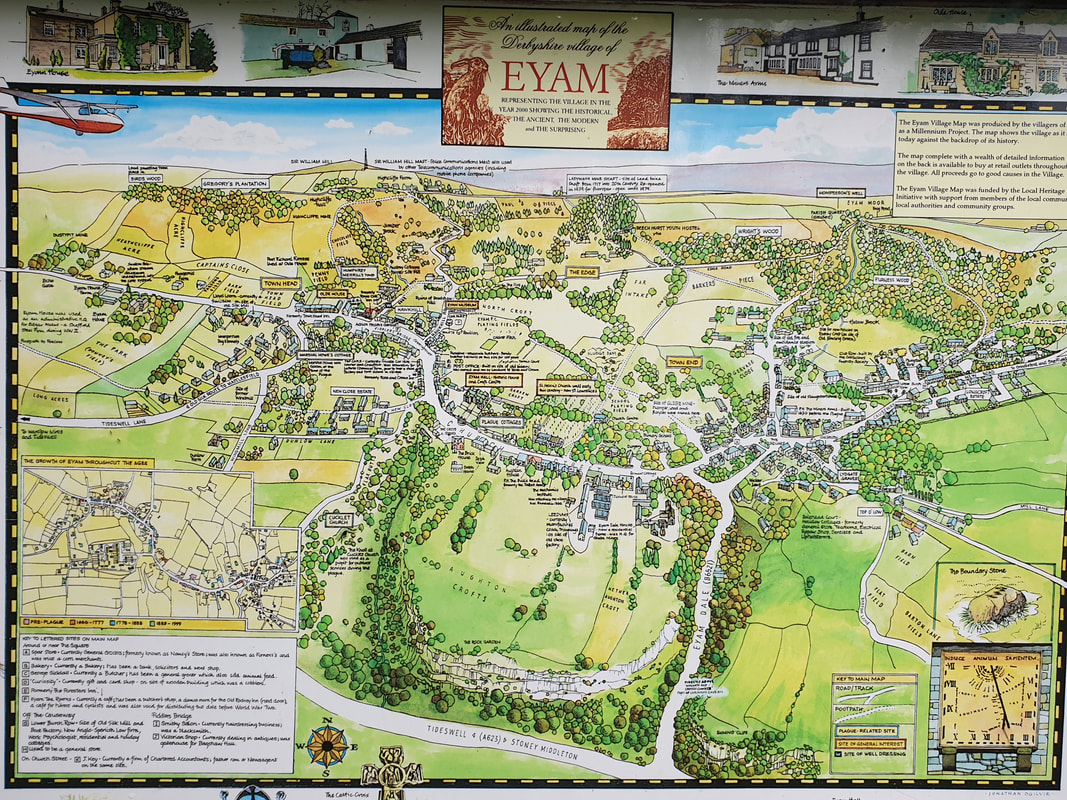

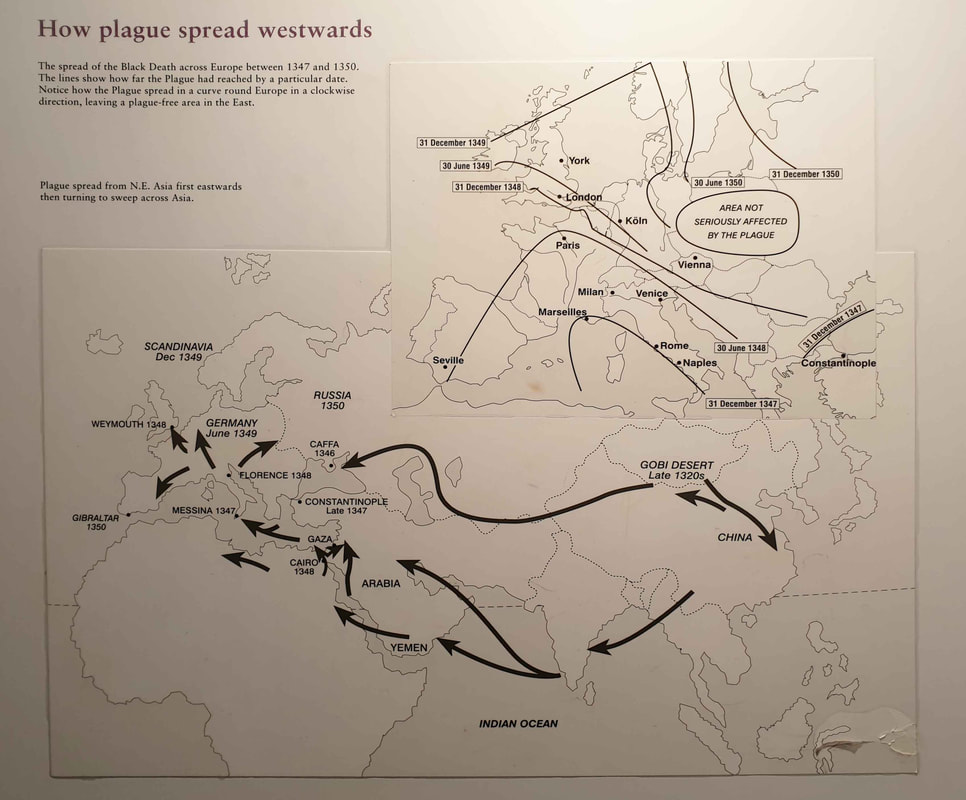

There is a light - so faint and far away - that it is only seen when all others have been extinguished. It was lit, centuries ago, when plague came to the Derbyshire village of Eyam - where they chose to hold the pestilence in a fatal embrace. By condemning themselves, within a 'cordon sanitaire', they saved the heart of England from contagion.

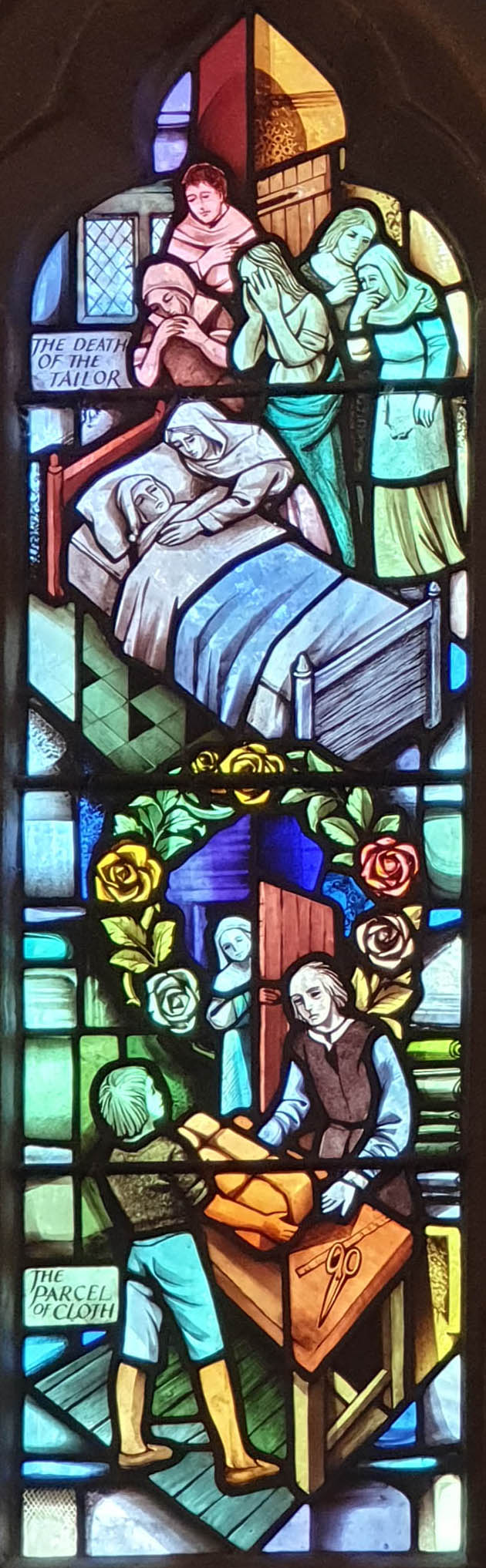

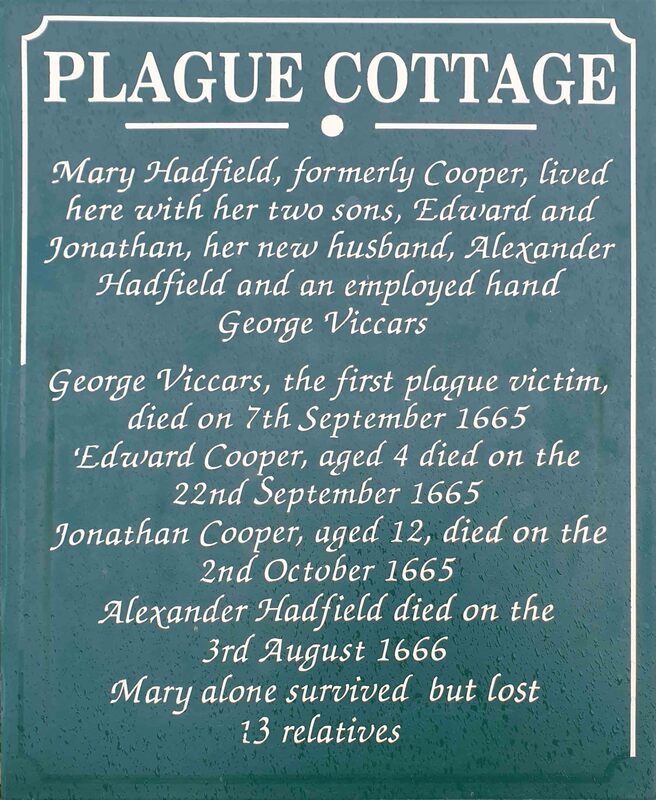

This story of humble yet heroic sacrifice begins in September of the Plague Year 1665 when a parcel of cloth arrived one rainy evening at the village of Eyam in the Peak District of central England. George Viccars, a tailor's assistant, hung the cloth to dry before the fire. The warmth revived the infected mites within the weave and they fall upon him in such numbers that by the following evening he is the plague's first victim.

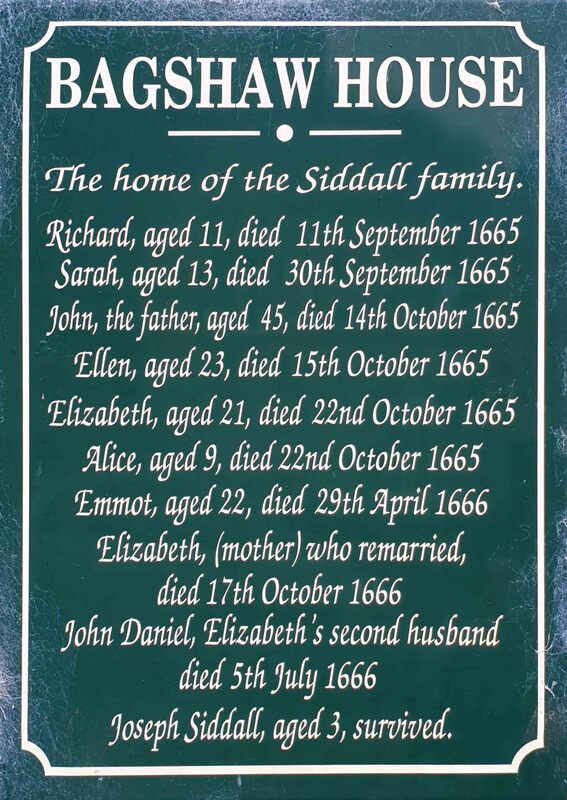

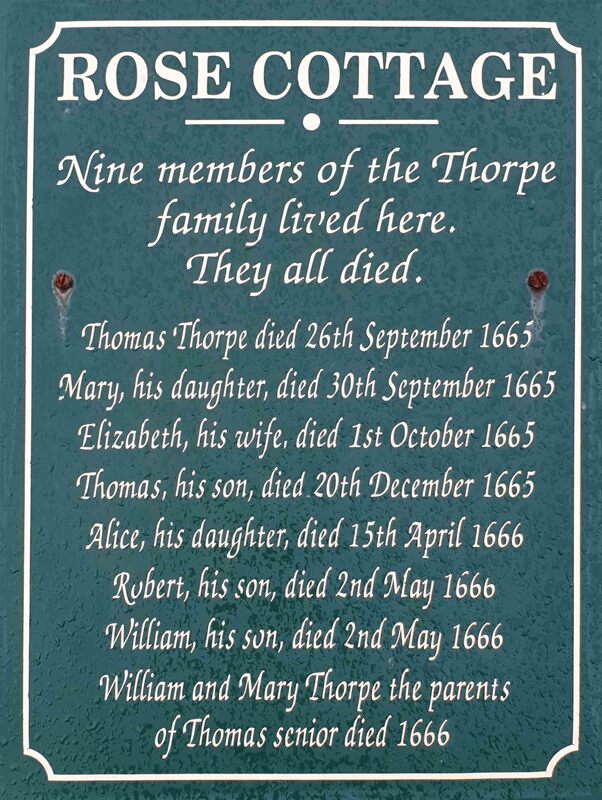

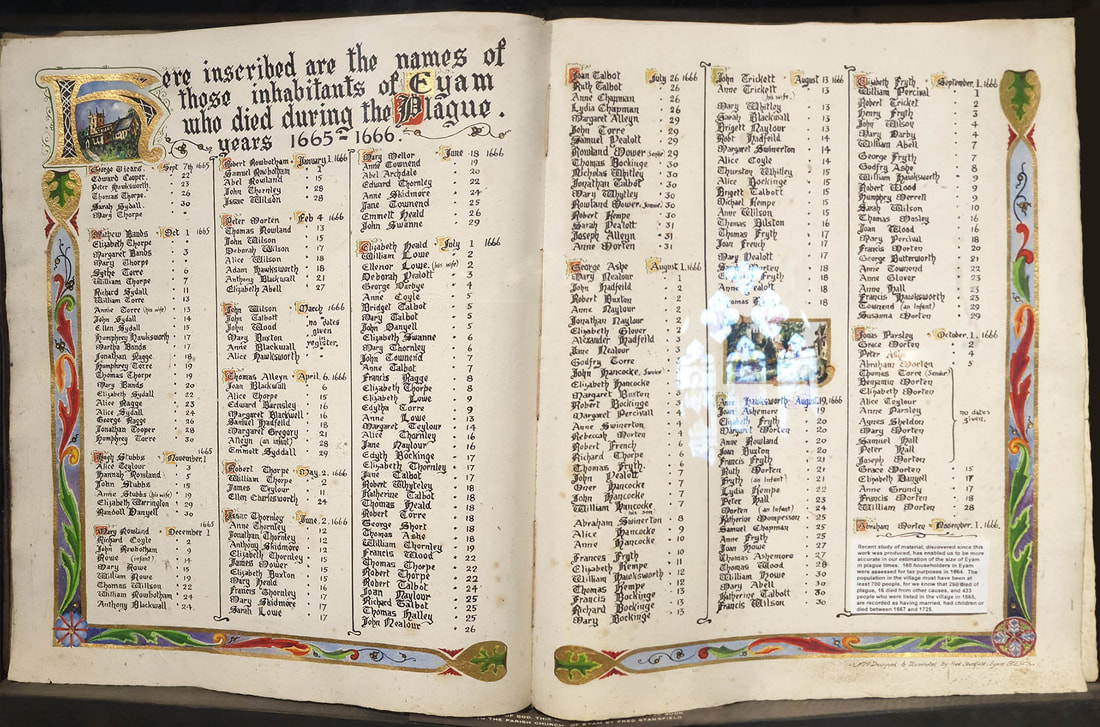

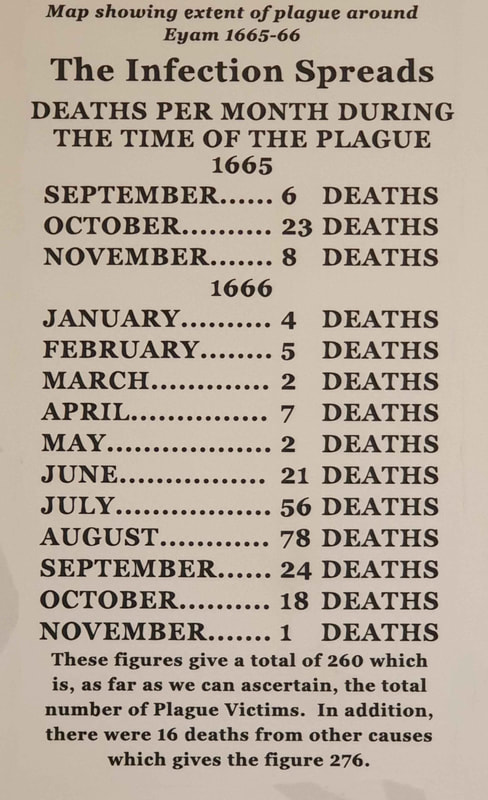

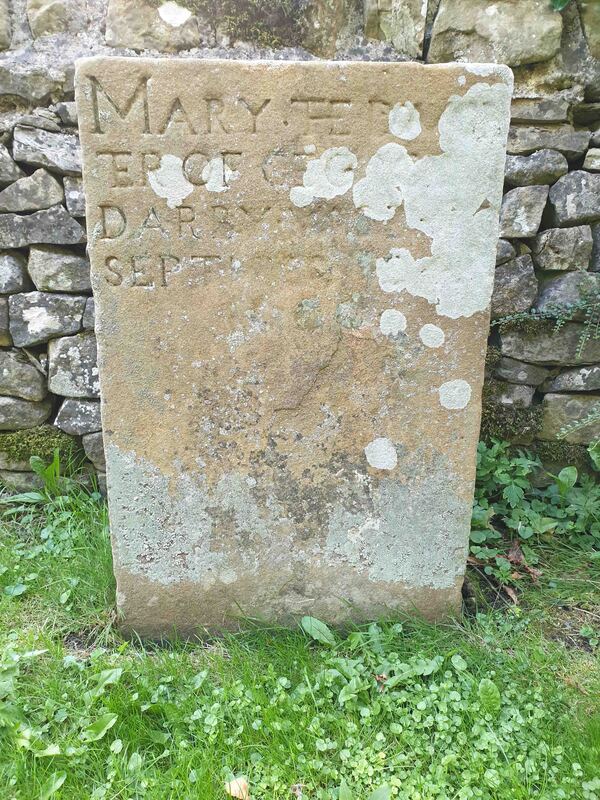

Only the mistress of the house, Mary Hatfield, would survive whilst her husband, two children and a score of relatives were enrolled in the Bills of Mortality. Out of the ten occupants of the house across the road, only 3 years old Joseph Syddall was spared. Whilst Parish Records indicate there were some 700 parishioners, who hosted the Eyam Wakes Festival, in the last week of August 1665 - it would appear that of the 350 Eyam villagers, there were 76 families affected - 260 plague victims - 16 deaths from other causes and just 74 who survived to see the Christmas of 1666. There is no such fraught accounting of the likely number of lives saved or the years of potential life lost during the last three centuries had the decision to self-isolate not been taken and the Black Death had escaped to run throughout the land. If a village were, like Malta, to earn a medal - Eyam's would be For Valour - not arithmetic.

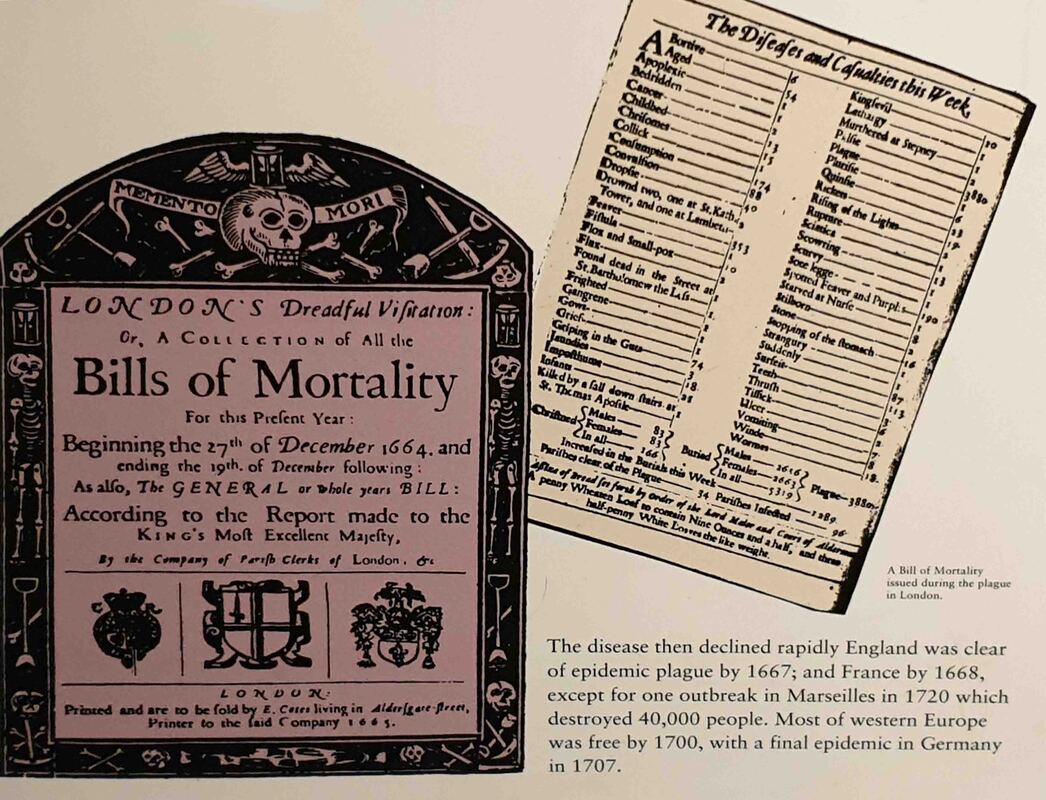

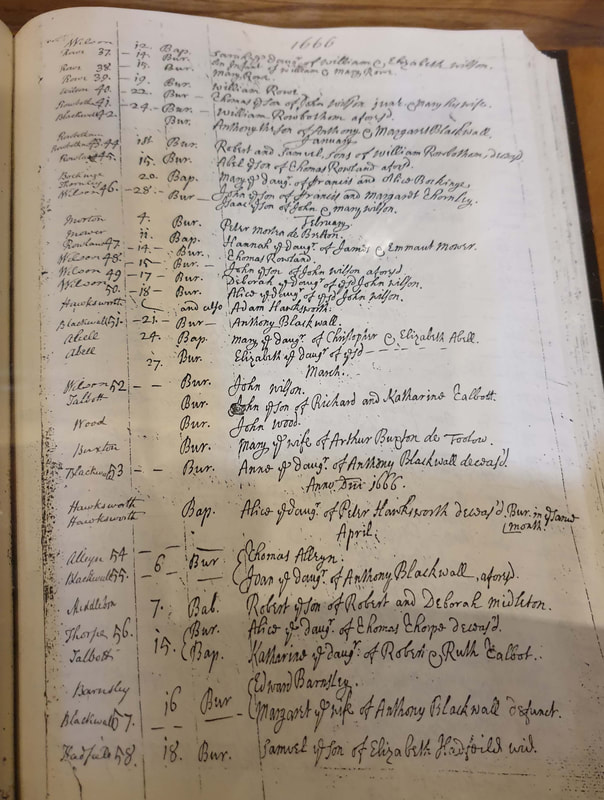

The Bills of Mortality

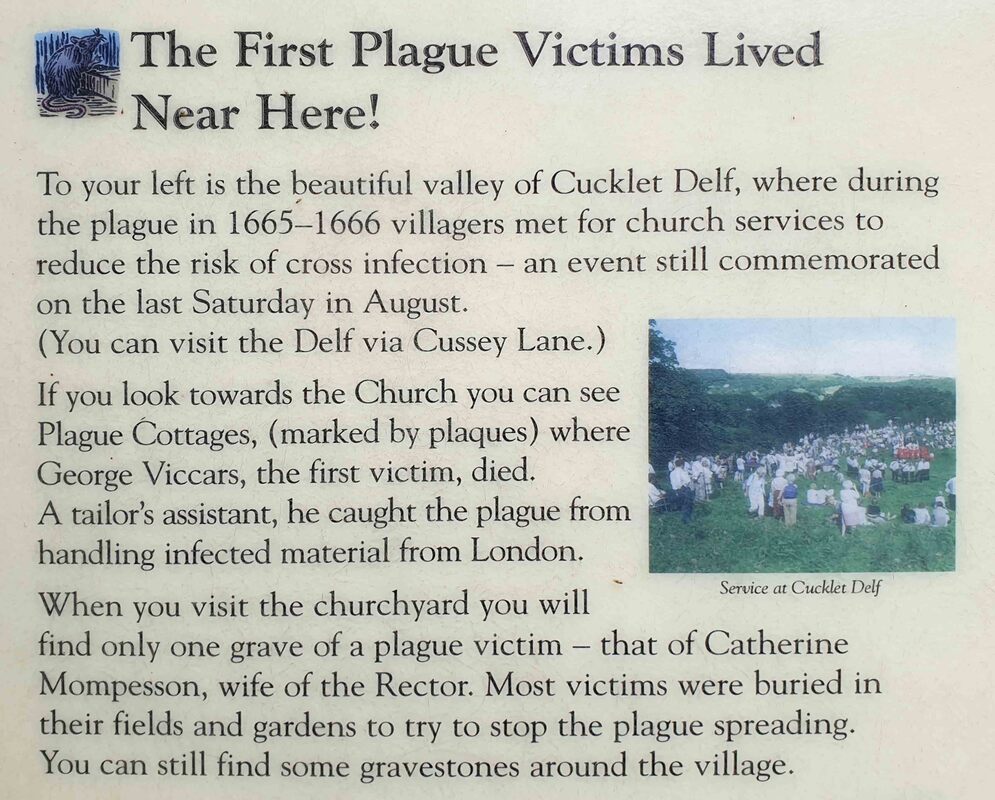

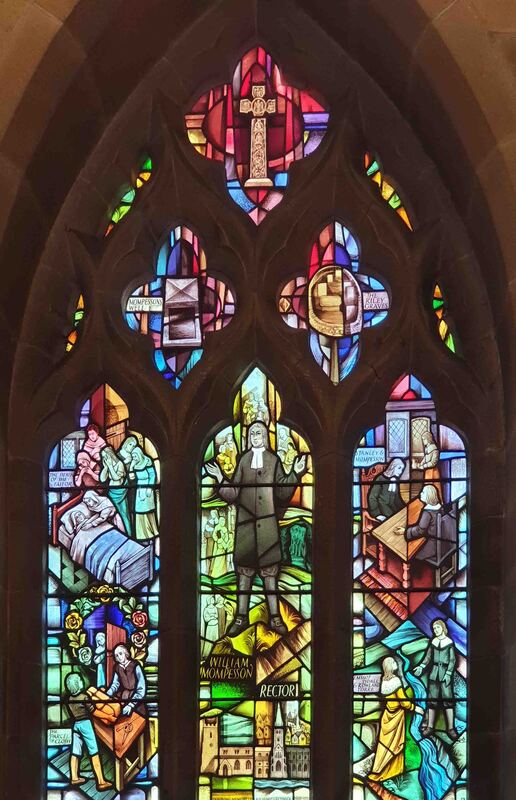

October 1665 saw 23 villagers taken but, as Winter's grip tightened, the numbers fell and continued to decline through the Spring of 1666. With only two deaths in May, it seemed the pestilence had all but burned itself away. Disaster returned in June with 21 deaths whereupon the new Parish rector, the Reverend William Mompesson and the former incumbent, Nonconformist Rev'd Thomas Stanley, forged an unlikely alliance to lead the parishioners into preventing the spread of the pestilence to neighbouring towns and villages by isolating themselves behind a 'cordon sanitaire' until the plague had passed or all within had passed away. With the guidance of Mompesson & Stanley and the support of the local landowner - the line was held and the plague contained. Thousands of strangers' lives were purchased for the lives of 260 loved ones.

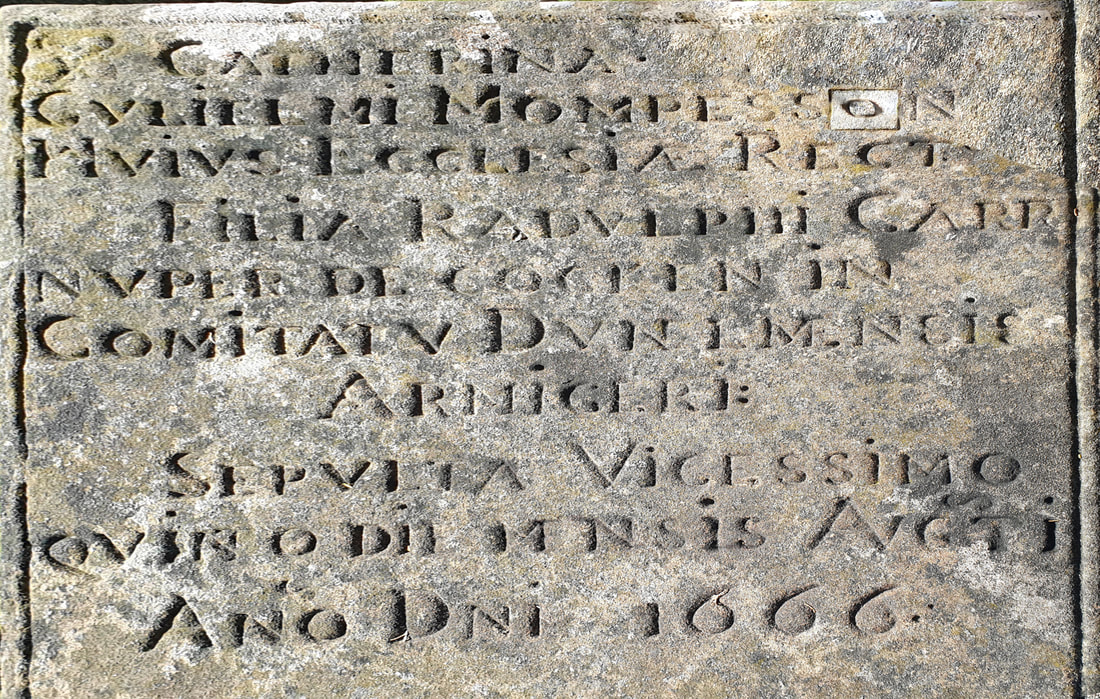

The death rate rose to 56 in July and peaked at 78 in August claiming the life of the vicar's wife, Catherine Mompesson. Though blaming himself for her loss and now believing himself to be close to death, William Mompesson and Thomas Stanley continued to minister to the sick and bereaved until at last as the death rate began to fall away from 24 in September down to just 18 in October. The death of Abraham Morten, on the 1st of November, was the last to befall the plague parish of Eyam which has come to exemplify courage and sacrifice in the darkest hours. The Rev'd Mompesson wrote "My ears never heard such doleful lamentations - my nose never smelled such horrid smells, and my eyes never beheld such ghastly spectacles."

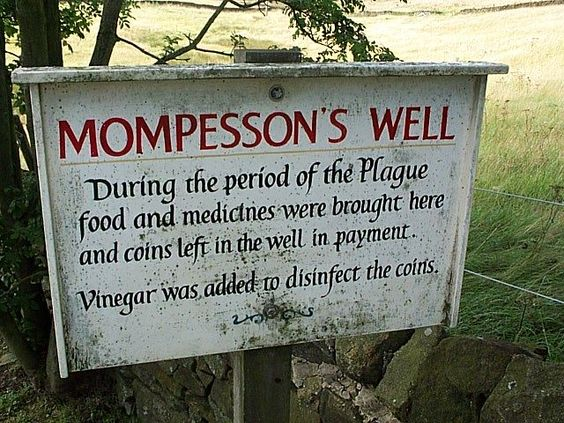

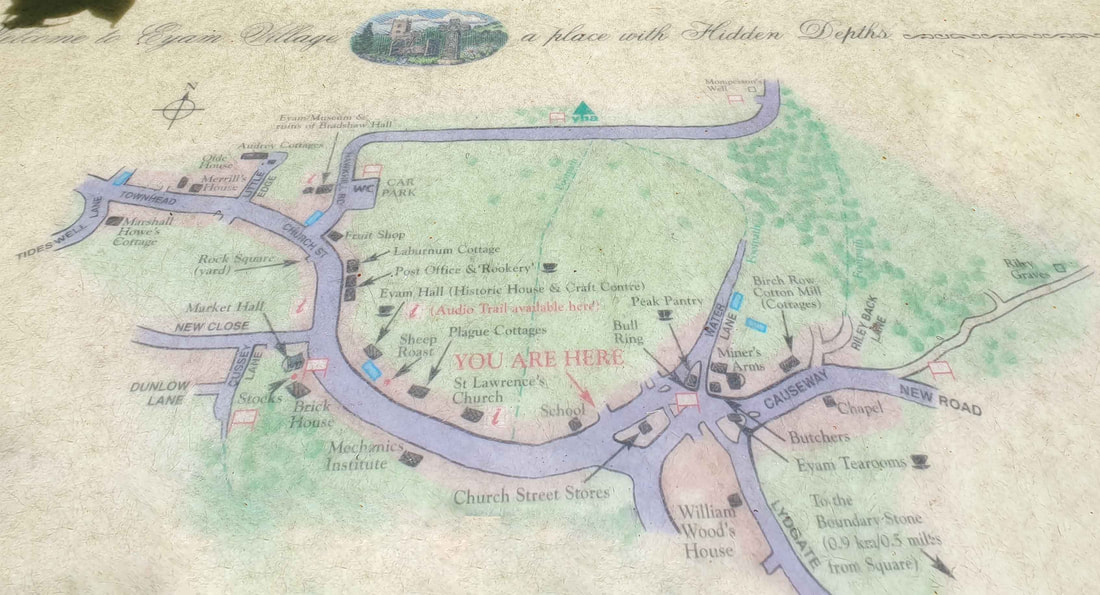

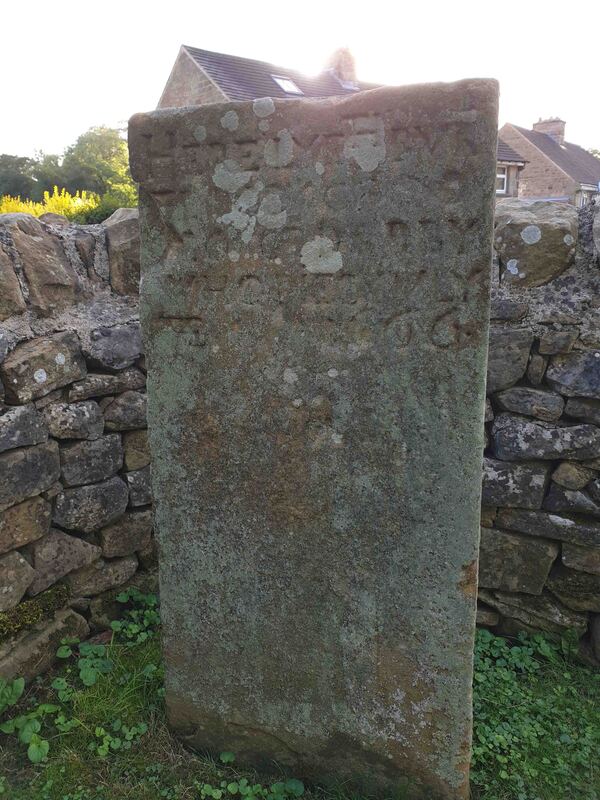

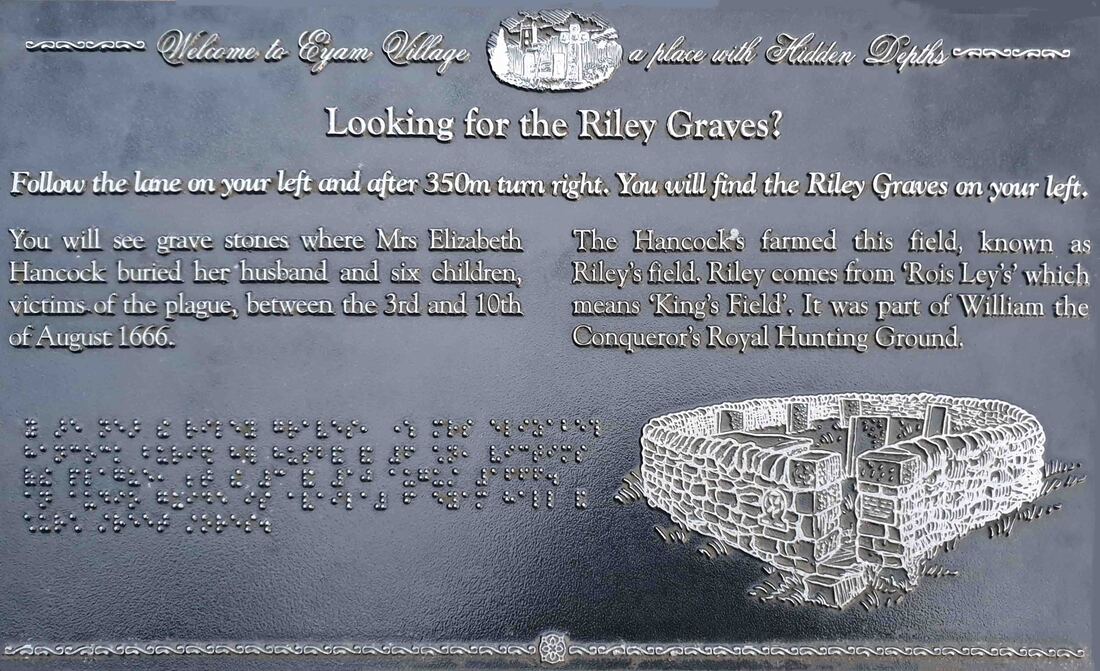

The following is not a Diary of the Eyam Plague nor a drawing out of the frailties of the data & the deeds of those long since departed. It is a reflection upon walks through the village of Eyam - in the Summer of 2019 - pausing at the Plague Cottages where the contagion first took hold - out to the Museum and ancient ruins - before returning past the village stocks & old Eyam Hall to the St Lawrence Church - there to wander through its graveyard where Catherine Mompesson lies. Down the hill past the triangular Village Square and up past the Lydgate Graves to the Boundary Stone with its coins still waiting in vinegar as payment for food that will never arrive. Then, as evening comes to the valley, its back down to The Causeway past the Siddall Butchers Shop and eastwards up to where the path divides through the wood and out upon the hillside as the sun sets upon the long forsaken Riley Graves where Elizabeth Hancock buried her husband and all six children. At last to return to the embrace of The Miners Arms wherein hang many of the relics shown below.

The Plague Cottages

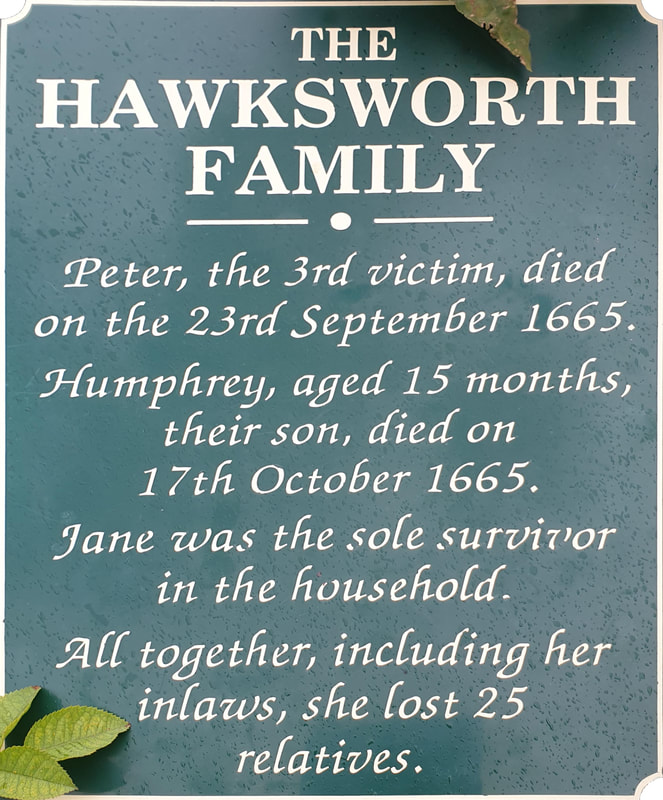

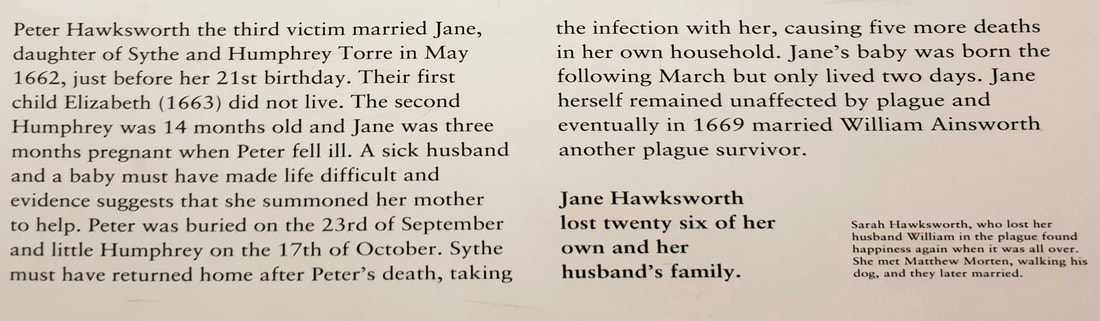

This unaccountable tragedy underscores the difficulty in achieving precise numbers. Amongst the scattered footnotes to this tragedy is the tale of how, one day upon Cucklet Delf where sermons were held during the plague - Matthew Morten's short-sighted dog dashed off to exuberantly greet Sarah Hawksworth - having mistaken her for its dead mistress - a chance encounter that began a relationship which, in time, led to their marriage.

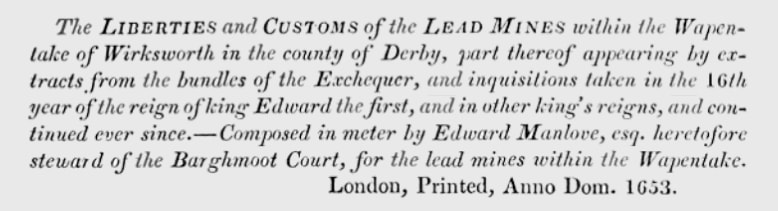

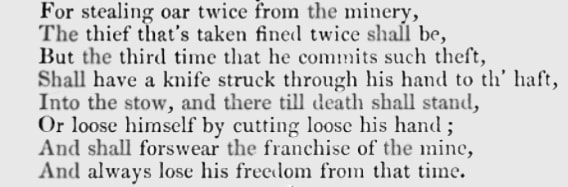

Eyam Museum

Mompesson's Well

|

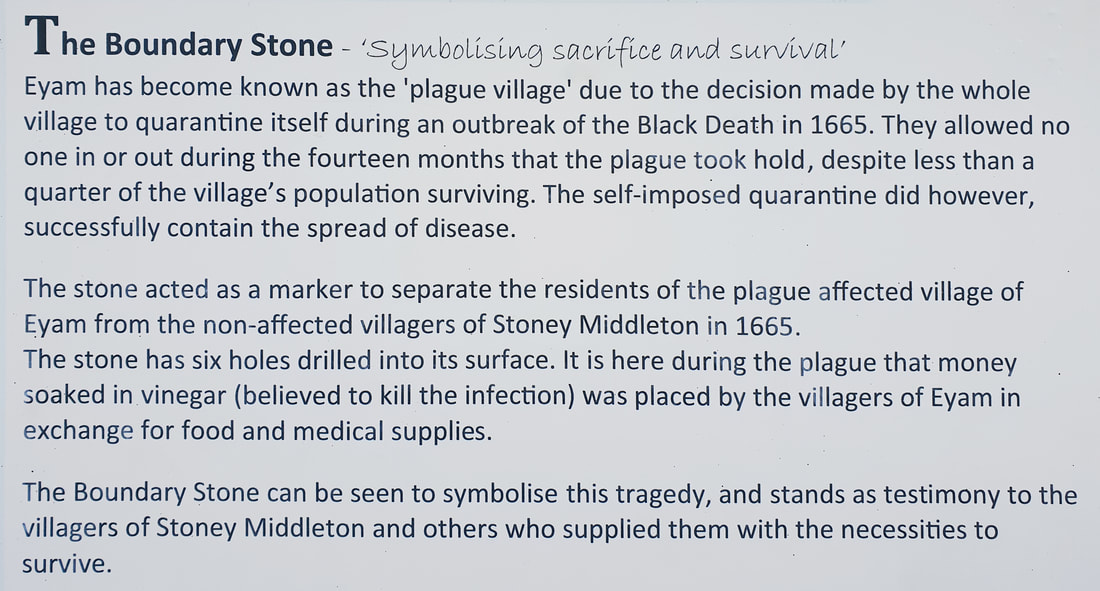

Up the hill, past the Museum, the road is joined by Edge Road and half a mile away is Mompesson's Well, on the northern boundary of the quarantine line. Here too were left coins in vinegar, as payment for food and medicines, provided by the neighbouring village in an arrangement supported by those villagers, Mompesson's fellow clergy and the Earl of Devonshire.

|

The Stocks & Eyam Hall

St Lawrence Parish Church & Graveyard

|

Catherine had begged her husband to abandon the village to its fate and in June 1666 succeeded in getting their 2 children sent to William's uncle, John Bielby in Sheffield. Though not robust, she insisted upon standing beside William and survived until 26th August 1666. Her's is the only marked plague victim's grave in the churchyard as others were buried at home to prevent contagion spreading.

Closing the churchyard was one of a suite of initiatives proposed by Mompesson & Stanley, as the only people of rank left in Eyam. These measures included outdoor worship; the cordon sanitaire and the Boundary Stone 'coins in vinegar' system also used at Scalby. Proposed at a public meeting on Sunday 24th June - they were in operation by 1st of July - some having already moved out of the village into shacks but within the quarantine line. There had been 21 plague deaths in June - which more than doubled in July to 56 and rose to the peak of 78 in August. Total isolation during this critical phase is seen as the principal factor in prevention of the spread of contagion to surrounding villages. |

When the graveyard was closed - parishioners were urged to bury their own dead on their own land and local lead miner, Marshall Howe - who had previously survived the plague - took on the job of Sexton, unafraid of contagion and eager for the rewards, despite the pleas of his wife. He laboured for two months and his rough handling of the corpses cost him a fee when, whilst carrying the body of Edward Unwin downstairs the dead man came to life and demanded a posset. Unwin survived the fall downstairs & was sufficiently revived, by his spicy alcoholic posset, to live a long & anecdote riddled life.

Howe, on the other hand, came to believe that he had carried the contagion home when his wife Joan died on 27 August 1666 and his only son William was taken three days later. It is said that this chastening experience improved his boastful and avaricious personality, as well as his handling of the deceased, as he continued his profitable and essential Sexton duties throughout the pestilence - remaining in Eyam until his death on 20th April 1698. His legacy lived long after him as mothers would threaten their unruly children with a visit from the fabled Marshall Howe.

Howe, on the other hand, came to believe that he had carried the contagion home when his wife Joan died on 27 August 1666 and his only son William was taken three days later. It is said that this chastening experience improved his boastful and avaricious personality, as well as his handling of the deceased, as he continued his profitable and essential Sexton duties throughout the pestilence - remaining in Eyam until his death on 20th April 1698. His legacy lived long after him as mothers would threaten their unruly children with a visit from the fabled Marshall Howe.

The Reverend Thomas Stanley

|

The Rev'd Thomas Stanley continued to live and serve at Eyam for the rest of his life. He died on 24th of August 1670 - St Bartholomew's Day - the eighth anniversary of his removal from incumbency in the parish of Eyam. Although the location of the grave is lost. - the great esteem in which he was held by the community is expressed in this stone that stands beside the church.

"It is more reasonable, that the whole country should testify their thankfulness to him, who, together with his care of the town, had taken such care as none else did, to prevent the infection of the towns adjacent". "He died in 1670, satisfied to the last in the Cause of Nonconformity, and rejoicing in his sufferings on that account." The Nonconformist's Memorial - Edmund Calamy The bicentenary of the ending of the plague was marked in 1868/9 by the renovation of the north aisle which contains a brass plaque:-

"The memorial Aisle was erected by Voluntary Contributions obtained in 1866, to commemorate the Christian and Heroic virtues of the Revd W. Mompesson (rector), Catherine his Wife, and the Revd T. Stanley (late rector). When this place was visited by the Plague in 1665-6, they steadfastly continued to succour the afflicted and to minister amongst them the Truths and Consolations of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The rebuilding and enlarging of the Aisle led to the restoration of almost the entire Church, in 1868-9, at the cost of £2,160." |

The Village Square

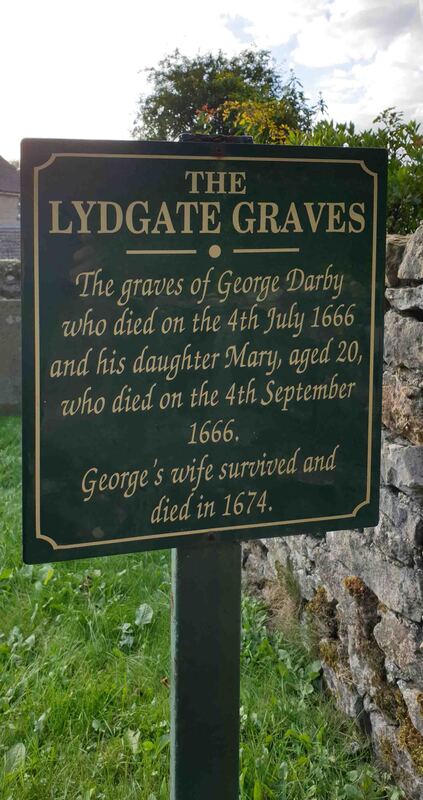

The Lydgate Graves

The Boundary Stone

|

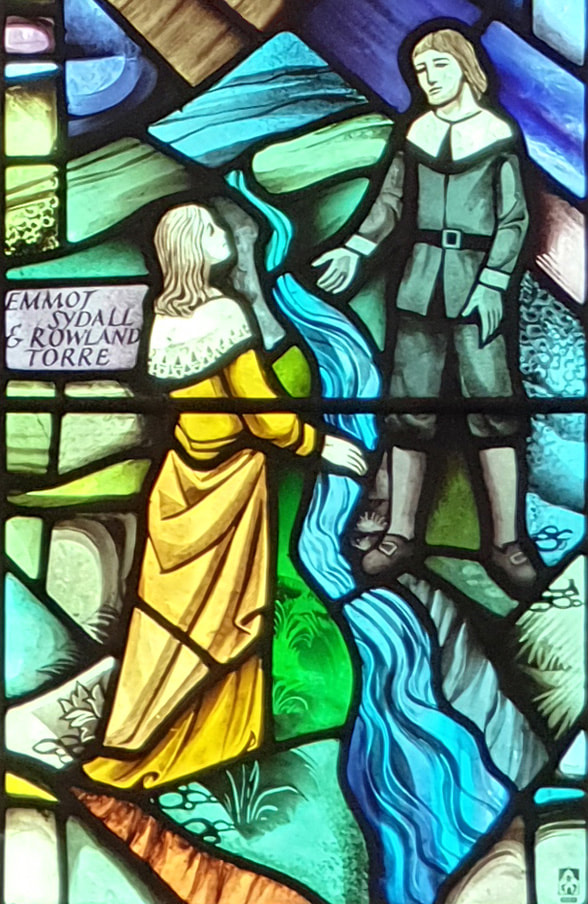

The Boundary Stone also recalls the tale of Rowland Torre and Emmott Syddall. She lived in Bagshaw House across the road from the Cooper's cottage where the plague had first taken George Viccars. Eight members of her family died leaving only 3 year old Joseph. She was in her early twenties when betrothed to Rowland Torre who would walk the mile or so from his village of Stoney Middleton to visit Emmott at Eyam until it became too dangerous. They would stand some distance apart, at the boundary between their villages, content to look upon eachother until the plague had passed.

Towards the end of April, Emmott no longer made their rendezvous at the boundary - against all hope Rowland continued to make the journey, trusting that somehow she had been spared. When, at last, the cordon sanitaire was lifted - he was amongst the first to enter Eyam to learn that she had died on 29th April in her 22 year. |

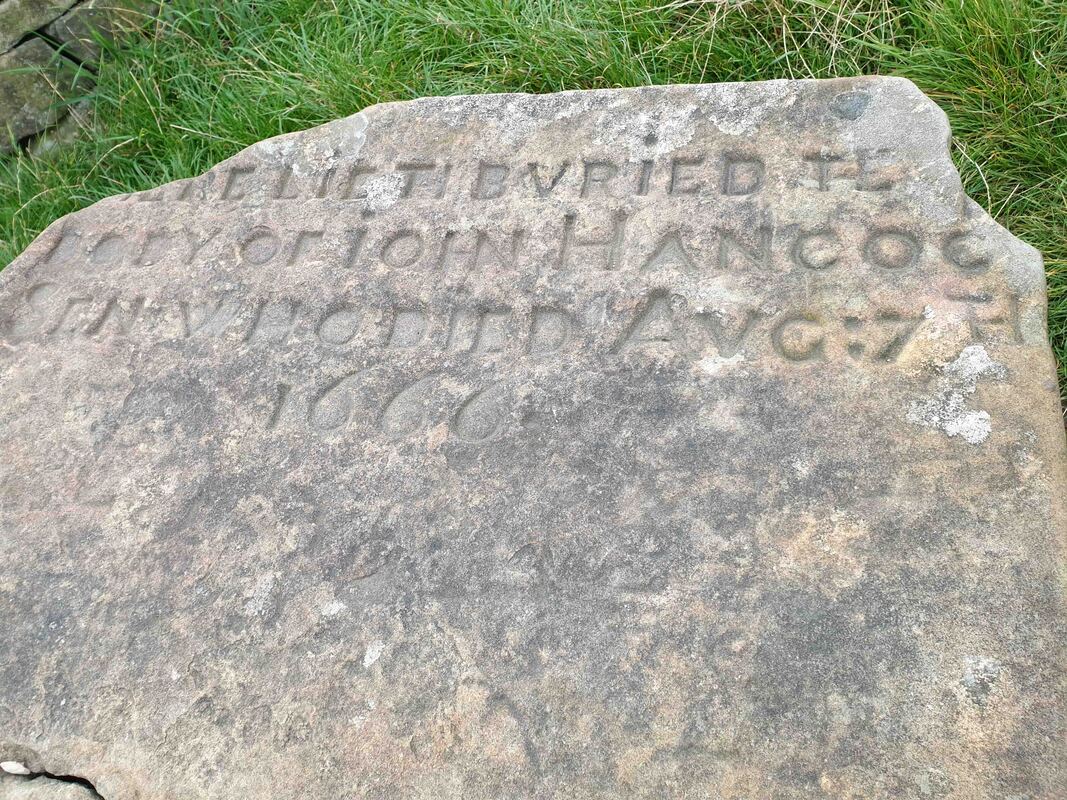

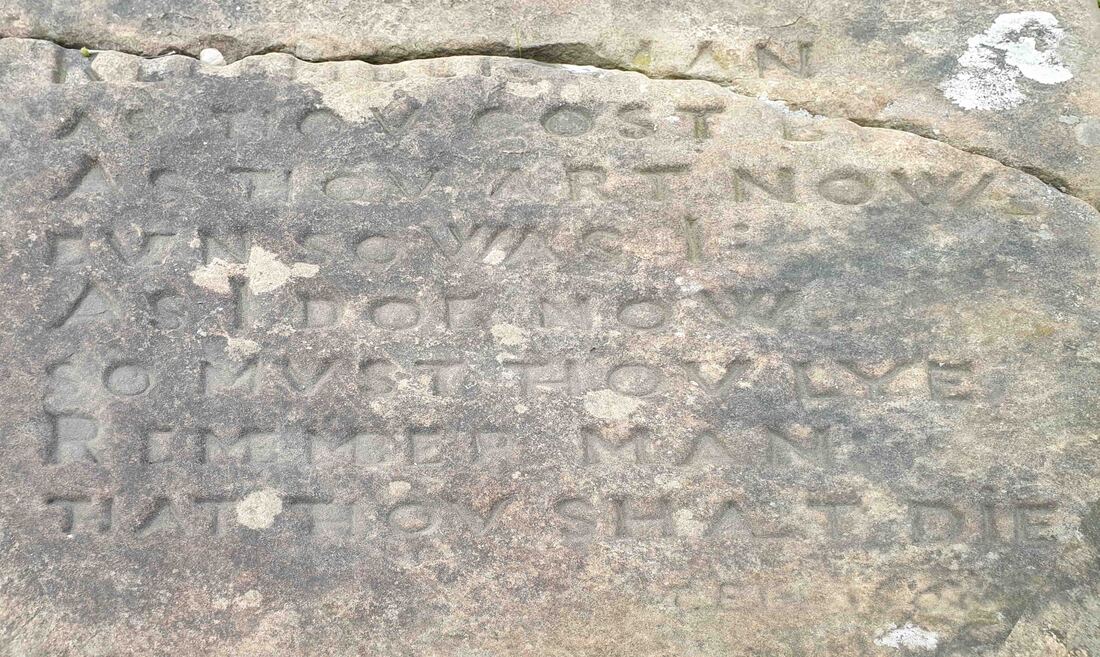

The Riley Graves

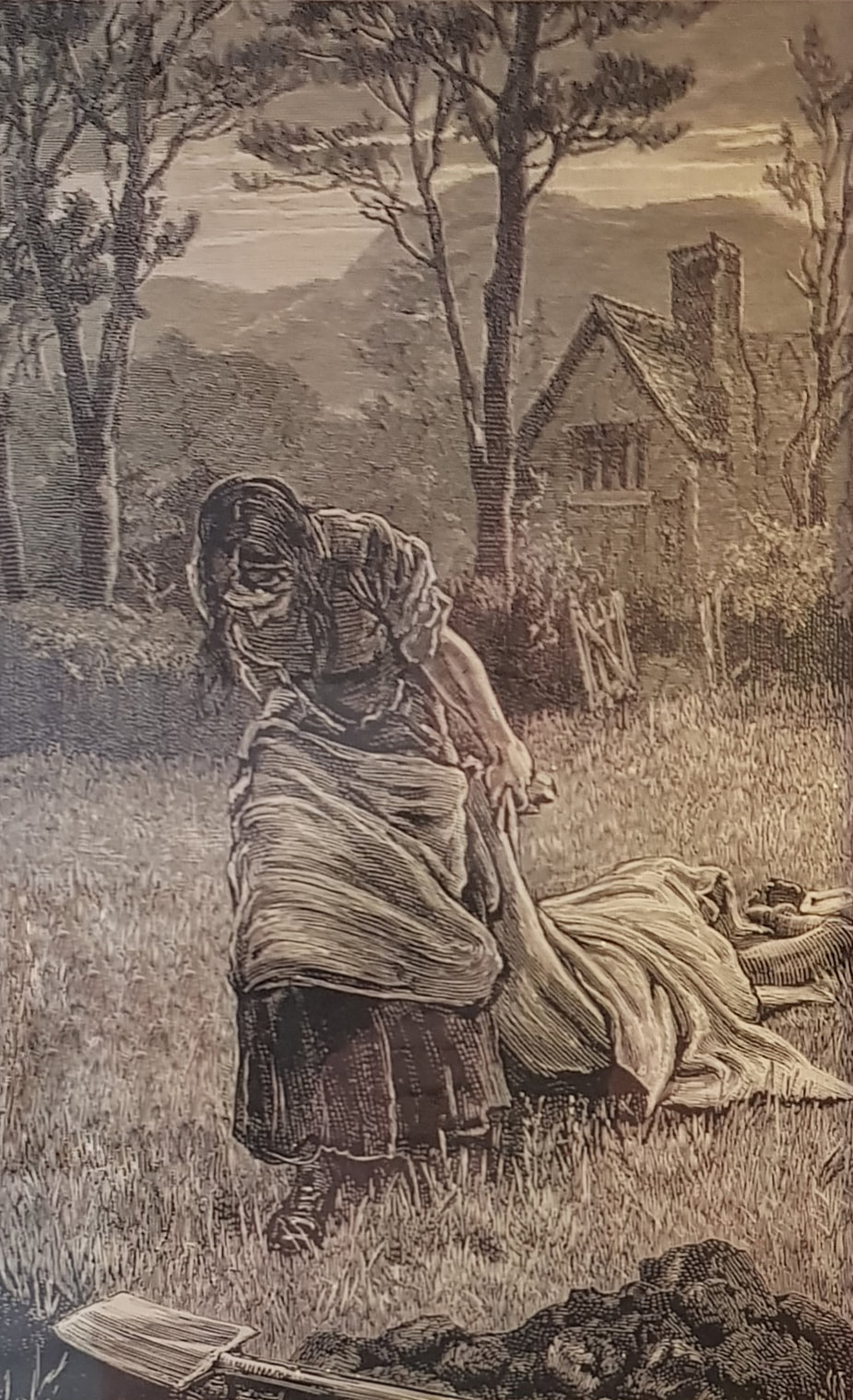

The harrowing tale of Elizabeth Hancock's ordeal took place high above the village as her family died around her between the 3rd and 10th of August 1666. Her extraordinary forbearance saw her drag the corpses across the field and burial in the sheepfold that embraces they yet. Beyond help and out of options she became the only person to break the quarantine line when she packed her scant belongings and headed for Sheffield.

Conclusion

The last word is from a letter by William Mompesson - aptly a Latin proverb "bonum magis carendo quam fruendo cernitur" - that which is good is perceived more strongly in its absence than in its enjoyment and that which the Bard rendered as:-

“For it falls out

That what we have we prize not to the worth

Whiles we enjoy it, but being lacked and lost,

Why, then we rack the value, then we find

The virtue that possession would not show us

While it was ours.” Much Ado About Nothing

“For it falls out

That what we have we prize not to the worth

Whiles we enjoy it, but being lacked and lost,

Why, then we rack the value, then we find

The virtue that possession would not show us

While it was ours.” Much Ado About Nothing

Sources & Resources

The Miners Arms was the only Inn in the village back then and it is the only one still open today - if you happen to stray inside please ask if they've found the key to the ancient strong box by the fire - even in Eyam, everything has to be somewhere.

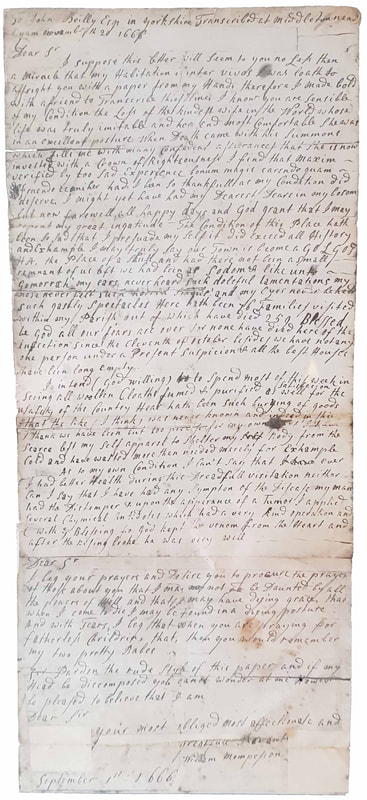

The Mompesson Letters

Three original letters by the Rev. Mompesson were preserved by a 'gentleman of Eyam' and survive in the Derbyshire Records Office. They were published in 1795 in 'Anecdotes of Distinguished Persons - Chiefly of the Present and Two Preceding Centuries', Volume 2 by William Seward & Published by T. Cadell Jun. & W. Davies of London'. William Seward was a descendant of the Rev. Seward who was displaced by Mompesson but became his greatest ally in persuading the villagers to hold the fatal embrace of quarantine.

| mompesson_letters.pdf | |

| File Size: | 4164 kb |

| File Type: | |

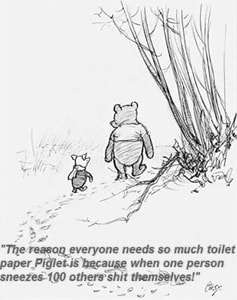

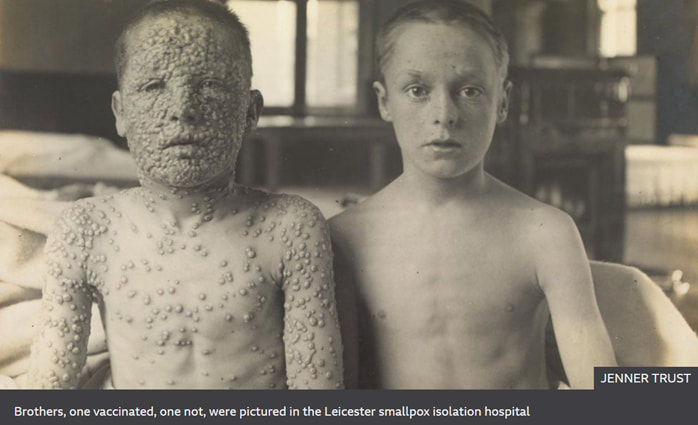

The emphasis today - as the COVI19 infection passes the million mark - is upon the courage, sacrifice and fortitude of humble people who paid such an extraordinary price to preserve the lives of others nearly 4 centuries ago. When the current pandemic is over, it will hopefully be possible to critically examine the Eyam story as a Public health test case and consider such issues as vectors, R Values and sentinel events such as vanishing toilet rolls.

The principal sources are those in and around the village. Eyam Plague Village by David Paul is good though the literary conceit of imagined characters and diaries goes a long way to demeaning the solid research and confidence in the narrative.

Viruses, Plagues, & History Michael BA Oldstone - photo dust cover

Daniel De Foe - Diary of a Plague Year 1665 is too important to leave out - 1666 Plague War and Hellfire by Rebecca Rideal which is mostly about 1665 and generally unhelpful - Eyam gets an 11 line paragraph & is almost worth transcribing for its ineptitude.

The Story of the Plague with a Guide to the Village by Clarence Daniels and The History and Antiquities of Eyam" by William Wood is a jewel.

"As yet untouched by Ruskin's abomination - the locomotive - Eyam retains most of its old-time characteristics, and will continue to attract visitors to the scenes of its mining struggles, and to the many other objects interesting to the antiquary and student of history.

"The plague, with its record of suffering and disaster, which beset the villagers, and the heroic attitude and actions of all concerned, of whom the rector was such a splendid leader, will ever be the subjects around which the chief interest will be centred, and it will be a bad day for our national character if they are ever allowed to slide into oblivion, and thus cease to awaken grateful thoughts and to inspire others to self-sacrificing devotion." W. Wood

"The plague, with its record of suffering and disaster, which beset the villagers, and the heroic attitude and actions of all concerned, of whom the rector was such a splendid leader, will ever be the subjects around which the chief interest will be centred, and it will be a bad day for our national character if they are ever allowed to slide into oblivion, and thus cease to awaken grateful thoughts and to inspire others to self-sacrificing devotion." W. Wood

Epidemiological Resources

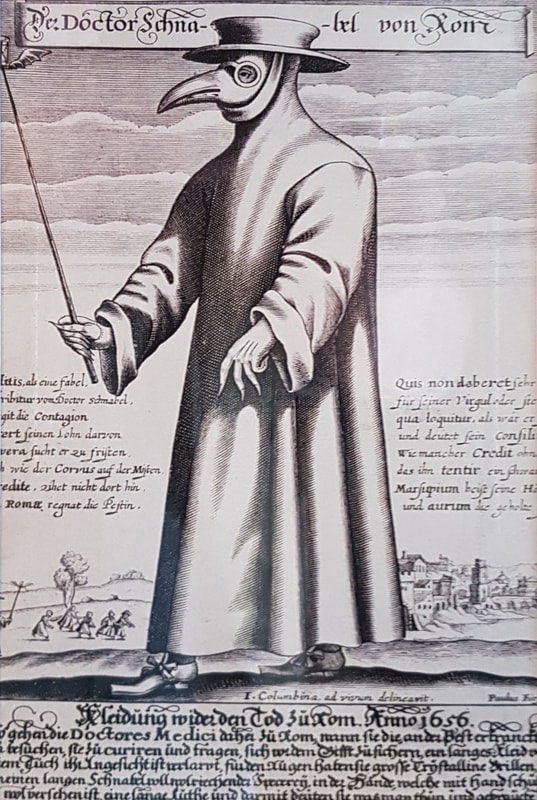

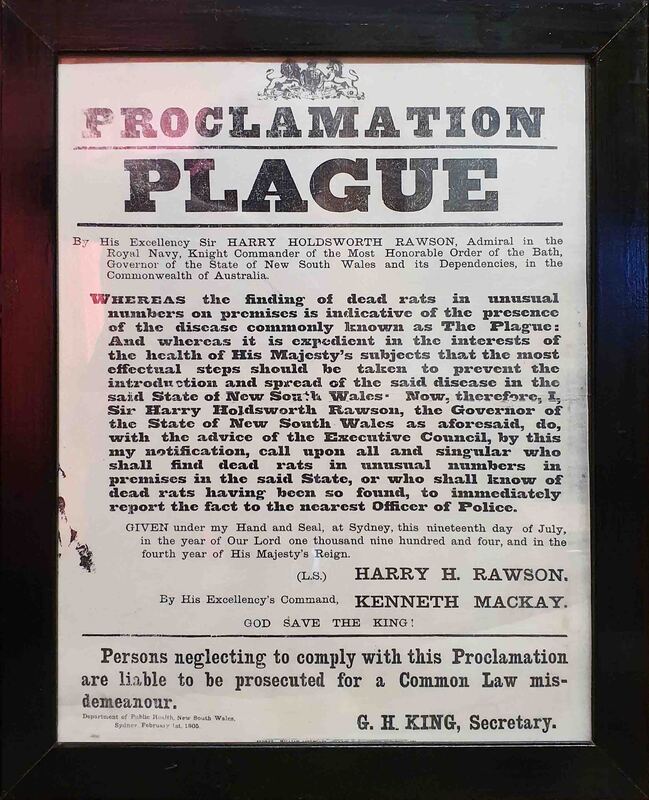

Justinian Flea - photo plague poster out of frame.

| royal_society_eyam_analysis_rspb.2016.0618.pdf | |

| File Size: | 852 kb |

| File Type: | |