The Boustead Jar

The Bousteads have lived at Shoal Bay for many years - active in the aquaculture & tourism industries but it was during his years as a crabber that the tidal range and shallow waters afforded Billy the opportunity to spend countless hours walking the inter-tidal zone. In 1998 he found the jar partly exposed on a Chenier ridge behind the fringing mangroves of a tidal creek.

The Darwin Museum (MAGNT) Curator of SE Asian Art at the time, after much consultation, concluded that it was of Spanish or Portuguese origin.

The Darwin Museum (MAGNT) Curator of SE Asian Art at the time, after much consultation, concluded that it was of Spanish or Portuguese origin.

THE BOUSTEAD JAR: A POSSIBLE PORTUGUESE CONNECTION TO NORTH AUSTRALIA (NT News Colin De La Rue)

Billy Boustead & Jar

Billy Boustead & Jar

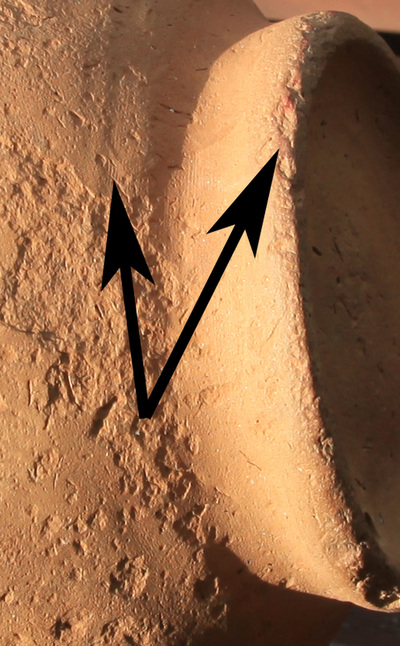

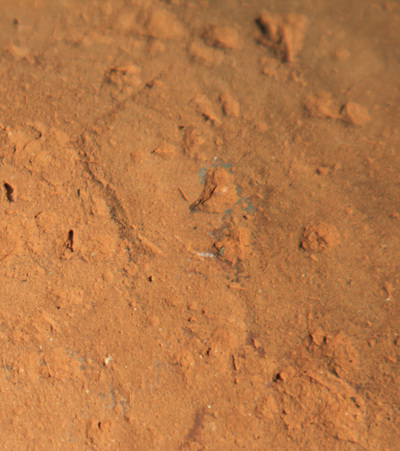

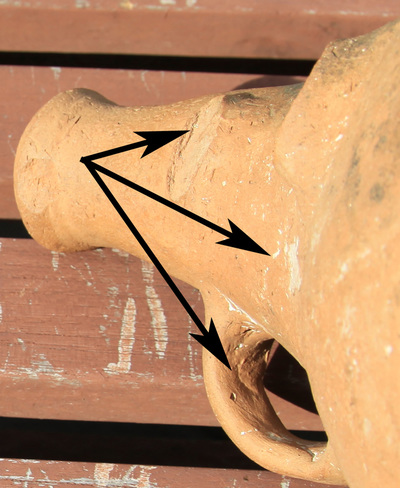

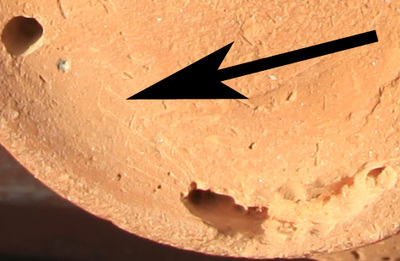

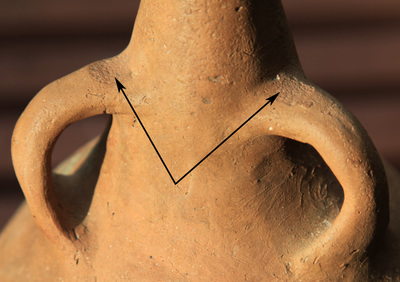

In May 1998, an earthenware jar, now known as the Boustead Jar, was found at Shoal Bay, near Darwin, by a member of a local fishing family, Mr. Bill Boustead. It was discovered partly exposed on a sand ridge beach behind a fringing mangrove copse on the southern shore of Shoal Bay. The jar was taken to the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory in Darwin for identification.

Although no positive identification was made, it was the option of the then Curator of Southeast Asian Art, after consultation with colleagues in both Indonesia and Australia, that the jar is most likely from southern Europe, probably of Spanish or Portuguese origin. The jar was subsequently returned to the owners.

In 2003 the jar was dated using thermos-luminescence at the University of Wollongong’s School of Geoscience. This produced a date of 490 (+/- 80) years BP. In the comments in the report it is stated. “In this case this result is thought to be better than the quoted +/ - 25% accuracy”.

Although no positive identification was made, it was the option of the then Curator of Southeast Asian Art, after consultation with colleagues in both Indonesia and Australia, that the jar is most likely from southern Europe, probably of Spanish or Portuguese origin. The jar was subsequently returned to the owners.

In 2003 the jar was dated using thermos-luminescence at the University of Wollongong’s School of Geoscience. This produced a date of 490 (+/- 80) years BP. In the comments in the report it is stated. “In this case this result is thought to be better than the quoted +/ - 25% accuracy”.

In July 2006 Jonathon Ostara, manager of Indo Pacific Marine

in Darwin brought the jar to the attention of researchers at Charles Darwin University

(CDU). The Boustead family was contacted and, with their permission, a preliminary report

on the jar’s finding was presented at the combined AIMA/ASHA Conference held in Darwin in

September 2006. Both Bill and his son David attended the conference presentation to help

establish the provenance of the find and answer questions from delegates.

The presentation looked at the circumstances of the find, as well as environmental conditions that may have supported both the preservation of the jar and its recent discovery. It also considered ways the jar may have made its way to the find spot. Recent archaeological studies undertaken at CDU by Dr Patricia Bourke on indigenous economies in the Darwin region, including Shoal Bay, have been useful when trying to understand the survival of the Boustead Jar on the beach ridge at Shoal Bay.

The jar was found on the most seaward to a series of sand ridges that lie across an extensive area of salt flats and mangrove forests. Significant environmental changes to the area are signalled at around five hundred years ago, the date obtained for the jar’s manufacture. Major infilling of the bay is indicated with concurrent movement of mangrove forest seaward, in some places by over one hundred metres. This process could well have protected the jar from exposure to subsequent damaging wave action.

The coastline of Shoal Bay today shows signs of mangrove regression with increased exposure of beach areas, again supporting the possibility of the recent exposure of the jar during monsoon weather. The region’s monsoon climate with a concentrated annual rainfall of around 1.5 metres may also have helped in preservation by leaching out destructive salts absorbed by the earthenware jar from seawater. (Rev. Colin de la Rue is a highly respected scholar whose work on the archaeology of Fort Dundas earned him an MA by research at CDU with a link to the thesis on the Fort Dundas page)

The jar was found on the most seaward to a series of sand ridges that lie across an extensive area of salt flats and mangrove forests. Significant environmental changes to the area are signalled at around five hundred years ago, the date obtained for the jar’s manufacture. Major infilling of the bay is indicated with concurrent movement of mangrove forest seaward, in some places by over one hundred metres. This process could well have protected the jar from exposure to subsequent damaging wave action.

The coastline of Shoal Bay today shows signs of mangrove regression with increased exposure of beach areas, again supporting the possibility of the recent exposure of the jar during monsoon weather. The region’s monsoon climate with a concentrated annual rainfall of around 1.5 metres may also have helped in preservation by leaching out destructive salts absorbed by the earthenware jar from seawater. (Rev. Colin de la Rue is a highly respected scholar whose work on the archaeology of Fort Dundas earned him an MA by research at CDU with a link to the thesis on the Fort Dundas page)

The Find Site

Hypotheses

'Three possible scenarios have been suggested for the jar’s arrival at Shoal Bay; European transport, Asian mariners, or drift voyaging. The date given by the thermo-luminescence report on the jar centres around 1513. The Portuguese first arrived in Southeast Asia at Malacca in 1509 and soon after that date moved further east to establish themselves in Indonesia’s Spice Islands. By 1511 the first Portuguese vessels were visiting the island of Solor in eastern Flores as well as some islands in Maluku. Solor became a safe anchorage and major contact point for Portuguese trading with the Spice Islands to the northeast and the sandalwood rich island of Timor to the south. Although these early dates for Portuguese activity in eastern Indonesia provide a context for the presence of the earthenware jar at Shoal Bay, they do not support any direct Portuguese connection with the area, and nor is there any evidence for Asian maritime activity there. Intensive Southeast Asian contact with North Australia, that of Macassan trepang voyaging, is generally considered to have begun a couple of centuries later. The third possibility is that the jar floated down to the north Australian coast from Eastern Indonesia.'

Sources & Resources

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Shoal Bay Environment

Blackfellas & Bush Chooks - The Shell Mound or Midden Controversy

“At the bottom of the western basin one of our people found the skeleton of a human body; and the skull and some of the bones were brought on board, but they were too imperfect to be worth preserving. The traces of natives were found every where, but they did not show themselves. In one of our excursions a tree was observed that had been cut down by some sharp instrument, and we had afterwards reason to believe that the natives were possessed of iron tools, which they might have obtained from the Malays. A curious mound, constructed entirely of shells, rudely heaped together, measuring thirty feet in diameter, and fourteen feet in height, was also noticed near the beach, and was supposed to be a burying-place of the Indians.” PP King 22 April 1818

The above image demonstrates how normal tidal action upon a shallow beach face conspires to accumulate shells in wing shaped ridges with steep leading and gentle trailing edges.

There is considerable controversy over the origin of the shell mounds that are a feature of the coastal fringe of north Australia. They are found in two styles, the classical pyramid mound and the linear ridge variety - occasionally in transition between the two.

One school maintains that they are middens left by generations of Aboriginal people eating shells in the same place and certainly Aboriginal people would sit on them because they are unpleasant for snakes whilst being high and dry. It is also an irresistible vantage point for anyone. Aboriginal oral history reports the hiding of tools & weapons in the mounds and occasionally the interment of bodies therein. The opposing school maintains that the mounds are aggregated and sorted up by tidal action and further raised by the obsessive compulsive action of the Orange Footed Scrub Fowl (Bush Chook).

There is considerable controversy over the origin of the shell mounds that are a feature of the coastal fringe of north Australia. They are found in two styles, the classical pyramid mound and the linear ridge variety - occasionally in transition between the two.

One school maintains that they are middens left by generations of Aboriginal people eating shells in the same place and certainly Aboriginal people would sit on them because they are unpleasant for snakes whilst being high and dry. It is also an irresistible vantage point for anyone. Aboriginal oral history reports the hiding of tools & weapons in the mounds and occasionally the interment of bodies therein. The opposing school maintains that the mounds are aggregated and sorted up by tidal action and further raised by the obsessive compulsive action of the Orange Footed Scrub Fowl (Bush Chook).

The Rise & Fall of the Shell Dune

The article below is The Weipa Shell-Mounds - Works of Man or Nature? by renowned anthropologist Bill Stanner. He talks about the North Queensland mega-mounds but the tropical, inter-tidal zone processes are exactly the same - unfortunately he had scant knowledge of bush chook dementia. Flinders extols their virtues when he is moored in Melville Bay. Aboriginals would once have taken a heavy toll of the birds and it has taken 40 years since Cyclone Tracy for them to again become numerous in Darwin - which affords much humbug but also an opportunity to observe their bizarre and most engaging behaviour. They all too readily demonstrate a diligence & co-operative industry entirely out of character with Darwin's suburban jungle.

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If seafood is cooked most common food poisoning bacteria and viruses will be killed; however, cooking won't remove all toxins and chemical pollutants in shellfish and fish. To avoid these risks, seafood should only be harvested from safe waters, chilled and stored correctly and purchased from licensed suppliers. Food Safety Information Council.

Johnson DL, Horwath Burnham J. Introduction: Overview of concepts, definitions, and principles of soil mound studies. In: Horwath Burnham JL, Johnson DL, editors. Mima Mounds: The Case for Polygenesis and Bioturbation: Geological Society of America Special Paper 490. 2012, p. 1–19. There are mound landscapes like this this all over the world including north and southern Australia. (Dr. T. Stone)

Channel Island Mounds

These images show mounds on Channel Island in Darwin harbour.

This is the site of the old quarantine station & leprosarium which is detailed at http://www.pastmasters.org.au/channel-is-centenary---quarantine-to-lazarette.html

The images below show a corrugated iron water tank that has been deposited by a cyclone. The mound has continued to grow around the tank.

Fear of the disease would have made this a no-go zone since its inception in 1931 and very probably since its earliest use for quarantining Chinese lepers which began in 1885.

There were severe cyclones in 1937 and Tracey in 1974. The leprosarium was closed in 1955 and it is certain that no Aboriginal people have camped here since that time.

The lack of fresh water, the proximity of graves and the lingering pall of the disease conspire to make this a distinctly undesirable camp.

The only other potential culprit with previous for mound building is still in residence.

This is the site of the old quarantine station & leprosarium which is detailed at http://www.pastmasters.org.au/channel-is-centenary---quarantine-to-lazarette.html

The images below show a corrugated iron water tank that has been deposited by a cyclone. The mound has continued to grow around the tank.

Fear of the disease would have made this a no-go zone since its inception in 1931 and very probably since its earliest use for quarantining Chinese lepers which began in 1885.

There were severe cyclones in 1937 and Tracey in 1974. The leprosarium was closed in 1955 and it is certain that no Aboriginal people have camped here since that time.

The lack of fresh water, the proximity of graves and the lingering pall of the disease conspire to make this a distinctly undesirable camp.

The only other potential culprit with previous for mound building is still in residence.