ARNHEMLAND'S LOST PAST

Rediscovering Yolngu Oral History

©Ian McIntosh

Citation:- McIntosh, I.S. 2020. Re-discovering Yolngu Oral History. PastMasters Publishing Issue 3.

Abstract

As a way of assessing the deep history of foreign visitation to northeast Arnhemland, this article analyses Yolngu oral history accounts of pre-Macassans, including groups known as the Wurramala and, in particular, the Bayini, who established a military camp on Australian soil in the late 1660s. The meaning of Murngin or Murrnginy, a collective term once used in describing the Yolngu group of clans, provides insight into the lasting legacy of these pre-Macassans from the former Sultanates of Gowa and Tallo in what is today Macassar in Indonesia. Interviews conducted with the late Warramiri leader David Burrumarra in the 1980s, provide the narrative and mythological content for this historical investigation.

In search of the past

The acceptance of oral traditions as valid historical sources has long been a topic of academic debate. Anthropologist Eric Wolf once called indigenous societies, ‘people without history’. It was not until the pioneering, interdisciplinary work of Belgian historian Jan Vansina in the 1960s that indigenous knowledge of history received widespread recognition.

Yet in Australia in 2020, indigenous knowledge of the past is only now being taken seriously. The common view that Aboriginal Australians were isolated from the rest of the world until the advent of British colonizers still has great currency. However, a careful and deliberate look at Yolngu oral tradition tells a very different story.

The Yolngu, previously known as Murngin or Murrnginy, have occupied the lands and waters of northeast Arnhemland for millennia. In the 1970s, Campbell Macknight, in a towering work of scholarship, documented one chapter of that lesser known history when he described Yolngu engagement with Macassan trepangers from South Sulawesi in the period c.1780 to 1907 (Macknight, 1976). This was Australia’s first international export industry and mobilized literally thousands of indigenous and non-indigenous labourers.

Macknight relied on extensive archaeological and archival research and was quite frank in his dismissal of Yolngu oral tradition and mythology relating to this period. He told me early on that he did not know what to do with those many ‘exotic’ stories such as how a pre-Macassan group called the Bayini came from the moon!

Yet in Australia in 2020, indigenous knowledge of the past is only now being taken seriously. The common view that Aboriginal Australians were isolated from the rest of the world until the advent of British colonizers still has great currency. However, a careful and deliberate look at Yolngu oral tradition tells a very different story.

The Yolngu, previously known as Murngin or Murrnginy, have occupied the lands and waters of northeast Arnhemland for millennia. In the 1970s, Campbell Macknight, in a towering work of scholarship, documented one chapter of that lesser known history when he described Yolngu engagement with Macassan trepangers from South Sulawesi in the period c.1780 to 1907 (Macknight, 1976). This was Australia’s first international export industry and mobilized literally thousands of indigenous and non-indigenous labourers.

Macknight relied on extensive archaeological and archival research and was quite frank in his dismissal of Yolngu oral tradition and mythology relating to this period. He told me early on that he did not know what to do with those many ‘exotic’ stories such as how a pre-Macassan group called the Bayini came from the moon!

Introducing David Burrumarra

|

In the 1980s, I set out to document this oral history in partnership with the late David Burrumarra M.B.E. of Elcho Island (c.1917-1994). Burrumarra was a clan elder and an authority on all matters traditional. However, he was also a self-described anthropologist and had long tired of certain magical or superstitious ways of viewing reality.

Like others of his generation, he had eagerly embraced Christianity but a strong rational streak made him carefully dissect the Yolngu past in the manner of a social scientist. He had been trained, so to speak, by some of the greats, including anthropologists Donald Thomson, Ronald and Catherine Berndt and archaeologist John Mulvaney but he had also read, and fully imbibed, the work of Clyde Kluckholm, author of the classic Mirror for Man, a copy of which had been gifted to him by Ronald Berndt in the 1950s (McIntosh, 1994). Burrumarra also learnt something of the social sciences from his older clan brother, Harry Makarrwola, who had worked closely with famed US anthropologist Lloyd Warner in the late 1920s at Milingimbi. |

|

The knowledge passed on from that association enabled Burrumarra to reconstruct the Yolngu past as history not just as compelling myths to guide everyday life.

Over a period of seven years, Burrumarra and I documented a surprisingly large range of outsiders who had interacted with Yolngu over many centuries. In Burrumarra’s retelling of Yolngu history there was a clear sequence. Over time, the skin colour of the visitors gradually changed from black in the first instance, to white, and from relations of reciprocity to patterns of abuse and domination. Of the truth of this history, Burrumarra said that there were no doubts (McIntosh, 2015). |

In 2012, many years after Burrumarra’s passing, I co-founded a group of anthropologists, historians, traditional owners and heritage experts called the PastMasters to investigate this Yolngu past in greater detail, in the manner of oral historian Jan Vansina. Our initial focus was to shed light on the 1944 discovery, on Burrumarra’s ancestral land, of five medieval coins from the Sultanate of Kilwa in East Africa. This project rekindled my interest in Arnhemland history and I returned in earnest to the field notes I made with Burrumarra in the 1980s. This is what I discovered:

The Wurramala

|

Indonesian boat crews, blown ashore during storms or lost overboard, were the first visitors and many of these survivors never returned. This had always happened. However, the first intentional visitors to Arnhemland were black Indonesian whale hunters known collectively as Wurramala.

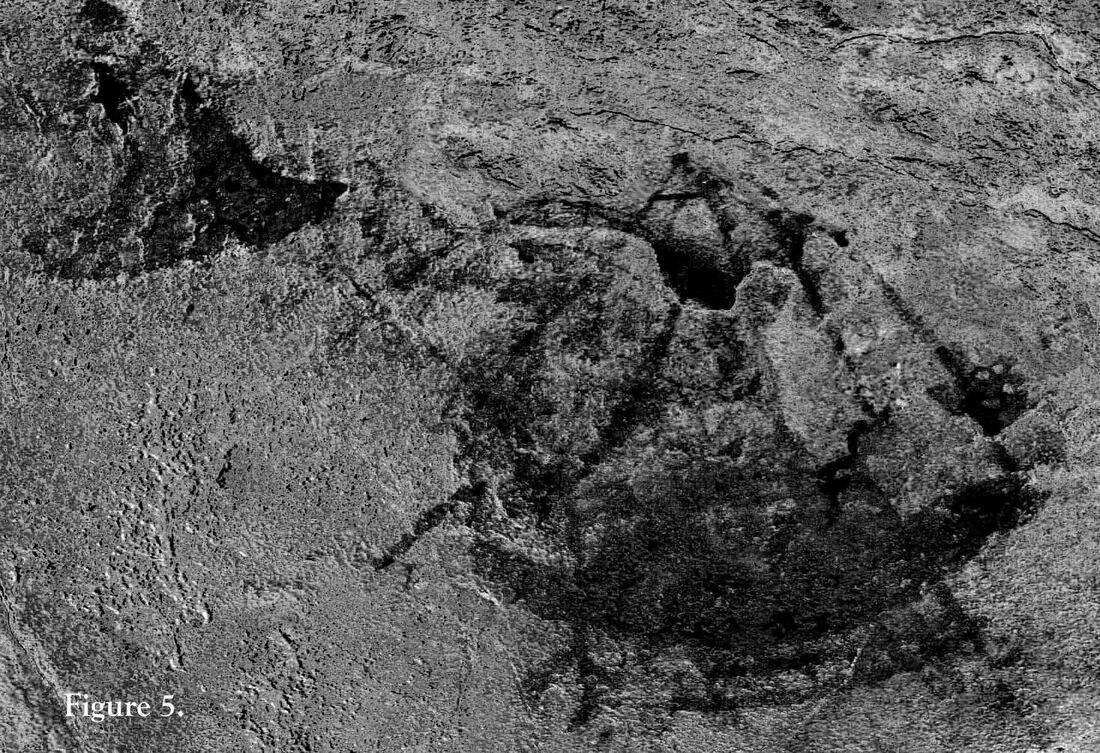

Oral history recounts that these hunters regularly interacted with Yolngu in the Wet Season and, on rare occasions, Yolngu had even visited their homelands to the north of Australia. Yolngu names for these totemic hunters include Turijene (Dhurridjini), who are Sama Bajau or ‘sea gypsies’ from the island of Samalona in South Sulawesi, a people with strong ritual links to the Sultanates of Gowa and Tallo in Macassar’s pre-trepanging days. The first archaeological evidence of these whale hunters is a rock art painting of what appears to be a kora kora or traditional warship of Maluku, which the PastMasters discovered on the Wessel Islands in 2013. |

The association of a harpooned whale with this elaborate sailing canoe supports the rich Yolngu oral historical accounts of the Wurramala documented in the 1940s by anthropologist Charles Mountford. However, Mountford believed that Wurramala were mythological creations and not actual people because Yolngu linked them with their ‘land of the dead’. Our archaeological discovery flatly overturns this view (McIntosh, et.al. 2020).

The Bayini

The next—and most extraordinary wave—was the golden-skinned pre-Macassans or Bayini. In our reckoning, this group was linked to the joint kingdoms of Gowa and Tallo from South Sulawesi. Burrumarra’s younger brother Liwukang and I visited the Royal House of Tallo in Macassar in the late 1980s to investigate the Arnhemland connection. From the early 1600s, this twin monarchy ruled many of the islands of eastern Indonesia until the Dutch and Bugis crushed them in 1667.

In retreat, members of these defeated kingdoms, as well as their associates, servants and soldiers, set up a military base on Yolngu land at Cape Wilberforce where they could regroup, staying for upwards of a generation.

According to Burrumarra, the arrival of what his generation called ‘Bayini’ in the late 1660s introduced Yolngu to the enormous power struggles underway in the waters to Australia’s north, namely Islam versus Christianity, English versus Dutch buccaneers and traders, and indigenous resistance to the lot.

The influence on Yolngu culture and religion was profound, with songs, ceremonies and names pertaining to these realities passed down to today, including the ubiquitous mast and flag motifs in Yolngu communities.

In retreat, members of these defeated kingdoms, as well as their associates, servants and soldiers, set up a military base on Yolngu land at Cape Wilberforce where they could regroup, staying for upwards of a generation.

According to Burrumarra, the arrival of what his generation called ‘Bayini’ in the late 1660s introduced Yolngu to the enormous power struggles underway in the waters to Australia’s north, namely Islam versus Christianity, English versus Dutch buccaneers and traders, and indigenous resistance to the lot.

The influence on Yolngu culture and religion was profound, with songs, ceremonies and names pertaining to these realities passed down to today, including the ubiquitous mast and flag motifs in Yolngu communities.

The Macassans

|

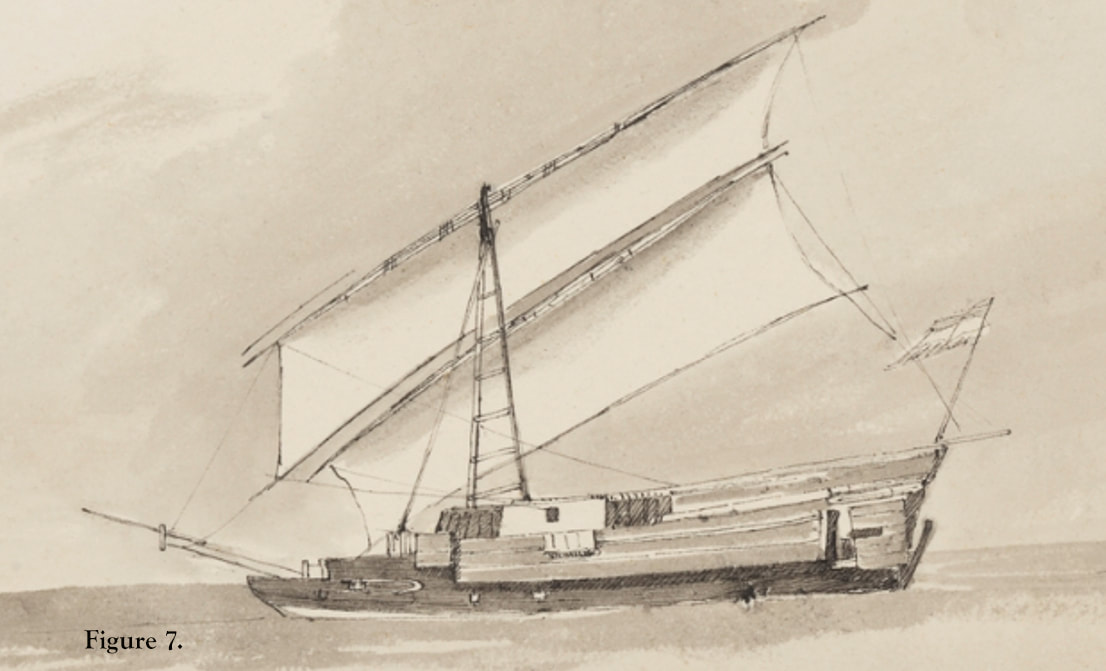

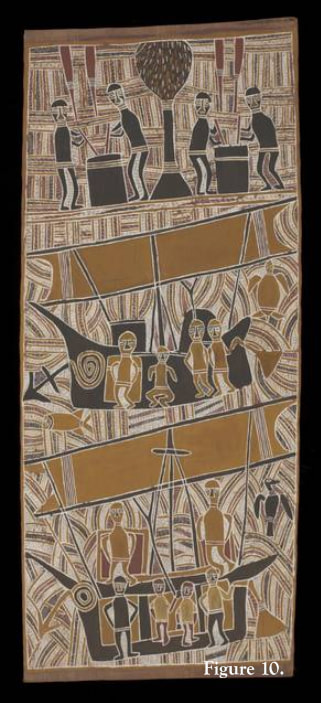

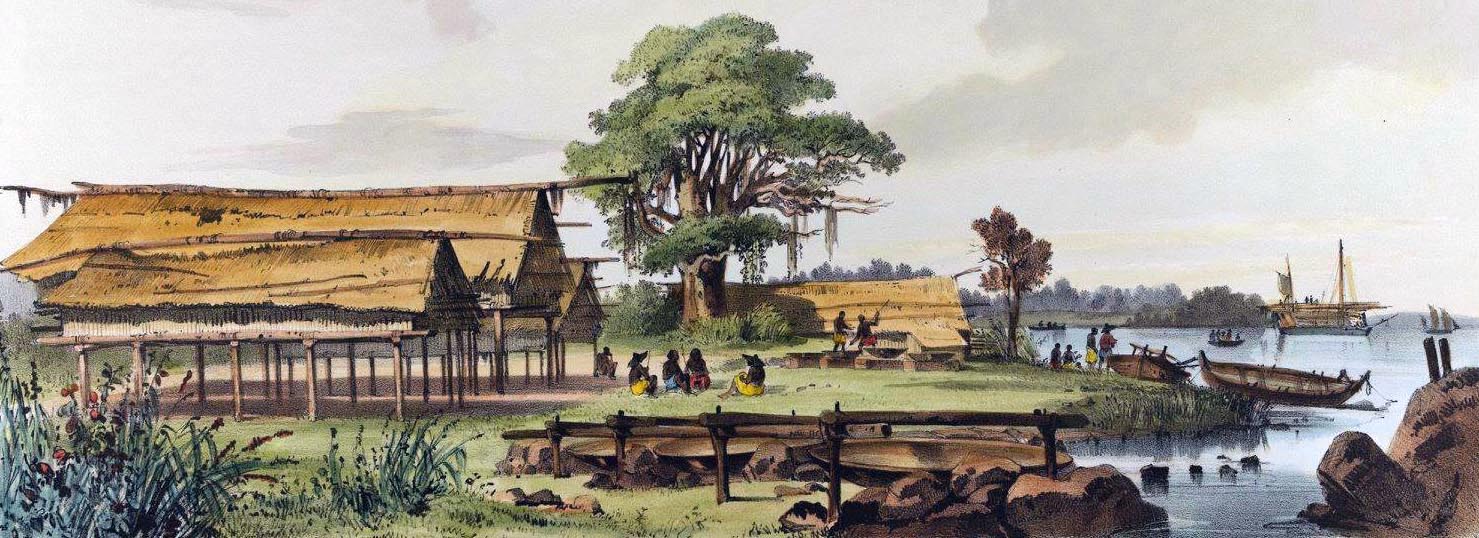

One hundred years later, in the late 1700s, the Macassan trepang industry commenced. There were two waves of engagement, an early and a late phase, and then in 1907 Macassan visitation came to a close (Macknight, 1976).

In contrast to the pre-Macassan era, which embodied an exchange of ideas and deep culture, the Macassan trepang period is far less significant in the ritual realm. Burrumarra and other Yolngu elders said to me that the earlier Wurramala and Bayini were on sacred business and brought with them notions of a high god, Allah, as well as many new technologies. The trepangers, on the other hand, were just businessmen. They used alcohol and tobacco as a tool for accessing Yolngu sea and land resources and were known to have abused Aboriginal women, causing all manner of social problems. Their relationship with Yolngu had no equivalent sense of honour (McIntosh, 2015). |

Australia’s first foreign settlement

|

Much about the Yolngu pre-Macassan past is recorded in Yolngu songs and personal names, including evidence for this large-scale military encampment in the late 1660s. If this was truly the case, and Burrumarra had no doubts, then the pre-Macassan military base was the first ever deliberate foreign settlement on Australian soil.

The Yolngu were not simply outsiders looking in as the settlement was established and grew. Rather, they were right inside the machinery of war. As Burrumarra said to me, this episode inspired the Yolngu to look deeply into themselves, who they were and to whom did they owe their allegiance. Setting aside these head spinning questions, many middle-aged and senior Yolngu men and women in the 1980s would speak openly about the ‘military times’ on Cape Wilberforce. Let me be clear. This era was not in any way associated with the trepang industry. In fact, the contrast could not have been greater. |

Yolngu terms, many originating from a pre-Macassan lingua franca, speak of how the base was on a war footing. For example, the word Dhawuyuma means men lined up on parade in readiness for battle. Then there are words for the commander of the troops, the captain of the ships, terms for discipline and punishment, honouring the flag, and so on. Power rituals with their hypnotic chants were also performed, some of which have been handed down to the present. These were all a great source of pride to Burrumarra, and probably contributed to his great love of the Australian armed forces, especially the Navy. It was a point of convergence for indigenous and non-indigenous traditions.

Many Yolngu personal names have their origin in this pre-Macassan period. Burrumarra and I recorded over two hundred including Gumpaniya, which is a direct reference to the awesome authority wielded by the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) or Dutch East India Company. In its day, the VOC was richer than Apple, Google and Facebook combined. The Company began its operations in 1602 and ceased in 1799, although the Dutch remained a colonial power long after.

What might it mean for a person to be named after the VOC? Yolngu visiting Macassar post-1780 with the trepangers could easily have picked up this term but the answer, in this instance, is found instead in the word’s deeper meaning for Yolngu.

What might it mean for a person to be named after the VOC? Yolngu visiting Macassar post-1780 with the trepangers could easily have picked up this term but the answer, in this instance, is found instead in the word’s deeper meaning for Yolngu.

The Birrinydji legacy

|

In the Yolngu frame of reference, the name Gumpaniya is the mythological Yolngu deity Birrinydji. It is a Dreaming entity for the Yirritja moiety, which is half of Yolngu society. The concept of Birrinydji, Burrumarra said, allowed Yolngu to absorb the shock of the new and turn it to their advantage, without compromising their traditions or identity. Burrumarra was the senior spokesperson for this law and, as they say in Arnhemland, he “lived right on it.”

The word Birrinydji is derived from the term for the Franks, the crusading Europeans whose quest for world domination—through the conquest of Islamic lands—began in the 1100s. Portuguese, Spanish and other freebooters continued this quest for “god, gold and glory” in the 16th century and beyond. These ‘Frankis’ were despised as infidels by Indian Ocean Muslims and other conquered peoples, and variations of this pejorative term appear throughout the world. For example, the ‘Franks’ are known as Folangki in China, Ferringhi in South-East Asia and Parrangi in the South Pacific. The foreigners’ beach in Malaysia is Batu Ferringghi. Even the word Vereenidge in the VOC brand name is a variation on this theme and is pronounced Ferringhi or Birrinydji. What can the Yolngu embrace of this term tell us about Yolngu history, especially in the pre-Macassan or Bayini period of the late 1660s? At a superficial level, Birrinydji might simply mean the white man, but it also refers to the power wielded by the Europeans in the colonial context. Yolngu knew the reality of this power to the north of Australia through their many external contacts, beginning with the Wurramala. They also reasoned that this power did not originate from the homelands of the whites, which were surely impoverished, but from the very lands of the conquered indigenous peoples. Indeed, the wealth of the VOC, who supplanted the Portuguese colonizers, came directly from the spices grown by southeast Asians. In the 1600s, the Banda Island chain to the north of Arnhemland was the epicentre of the global trade in nutmeg and mace. A good number of Yolngu songs, ceremonies and personal names reference the ‘big people’ who lived at Banda and how those islands were blessed with a great treasure that various nations had coveted since the dawn of time including the Arabs, Persians and Chinese. |

Burrumarra knew of the importance of Banda, if a little obliquely, through the songs and narratives of his Warramiri clan. However, the philosophy that Birrinydji’s strength came from such land, including his Aboriginal land, was clear as day. Why had the pre-Macassans, known as the Bayini chosen the power centre of Cape Wilberforce as the base of their military operations? What was hidden beneath the sand that offered them what they so desired? Burrumarra answered that Birrinydji had planted something on the beach at the beginning of time, a gift to make people’s lives long and healthy. They could prosper just as the Bayini did, if they followed Birrinydji’s law.

Cape Wilberforce was indeed a precious gift, and the visitors honoured the land and the Yolngu accordingly.

In Burrumarra’s telling of this story, these tall, golden-skinned bearded men in their long sarongs were the bringers of the law to Arnhemland. They were men of honour and he would call them Yolngu, his very own ancestors.

The term Bayini, which is used to describe this period of visitation, can be confusing because people of Burrumarra’s generation would also describe them as their very own people.

The Yolngu and the pre-Macassan Bayini were “one.” (Bayini is also the name of a Dreaming entity, as Burrumarra and I have described elsewhere. (See McIntosh, 2015)

In Burrumarra’s telling of this story, these tall, golden-skinned bearded men in their long sarongs were the bringers of the law to Arnhemland. They were men of honour and he would call them Yolngu, his very own ancestors.

The term Bayini, which is used to describe this period of visitation, can be confusing because people of Burrumarra’s generation would also describe them as their very own people.

The Yolngu and the pre-Macassan Bayini were “one.” (Bayini is also the name of a Dreaming entity, as Burrumarra and I have described elsewhere. (See McIntosh, 2015)

|

Apart from Yolngu oral history, the only other known reference to the presence of these early visitors in Arnhemland is Campbell Macknight’s interview with one of the last trepangers on the Australian coast.

Mangellai recalled how a group from the kingdoms of Gowa and Tallo had fled to north Australia after their defeat in the war of 1667 staying in northeast Arnhemland for upwards of twenty years. Mangellai identified Port Bradshaw (Yalangbara) as the place of retreat and this is backed up in Yolngu accounts. However, Burrumarra’s version is that Port Bradshaw was a secondary base, as was southern Arnhem Bay, and there were also various lookout posts on the Wessel Islands. |

The Gowa and Tallo visitors (Bayini) apparently thought that northeast Arnhemland was an island. They tried to circumnavigate it by starting in Port Bradshaw, travelling around Cape Wilberforce into Arnhem Bay and then south along the Gurrumurru River, as far as possible, before turning back.

Yolngu oral history and myth record this entire journey in considerable detail and even today the narratives describe the dangerous three-channel passage between Cape Newbald and Mallison Island, the latter which they called Gowa (Gawa). It is not known whether these visitors had longer-term plans for permanent settlement in Australia but the narratives strongly suggest, at the very least, that Yolngu were scouts on these voyages of exploration.

My detailed conversations with Burrumarra led to a number of publications detailing the rich life of these military settlements, where black, brown and white people, all with differing skill sets, intermingled (See McIntosh, 2015).

According to the narratives handed down to, and passed on by Burrumarra, there really was unity in diversity. Some of the residents had specialized professions like iron-making or dress-making while others were strictly soldiers or sailors. Even the ‘sea-gypsy’ Wurramala were there. All revered the great leader of the base, a man named Luki or Samaluki, who was described by Burrumarra as a godly figure, a Garayeng.

My detailed conversations with Burrumarra led to a number of publications detailing the rich life of these military settlements, where black, brown and white people, all with differing skill sets, intermingled (See McIntosh, 2015).

According to the narratives handed down to, and passed on by Burrumarra, there really was unity in diversity. Some of the residents had specialized professions like iron-making or dress-making while others were strictly soldiers or sailors. Even the ‘sea-gypsy’ Wurramala were there. All revered the great leader of the base, a man named Luki or Samaluki, who was described by Burrumarra as a godly figure, a Garayeng.

The Murngin (Murrnginy)

The sense of partnership enjoyed with the pre-Macassan visitors is at the heart of the term ‘Murngin’ (Murrnginy) adopted by Lloyd Warner in the 1930s to describe the entire Yolngu block of clans. With pastoralists encroaching on Yolngu lands from the south, Japanese pearlers from the north, and missionaries inviting themselves into Yolngu lives in a manner reminiscent of the pre-Macassans, Yirritja clans with custodianship of the Birrinydji legacy, like Harry Makarrwola’s Wangurri clan and Burrumarra’s Warramiri clan, were called upon to help negotiate this period of change.

Burrumarra’s mentor, Harry Makarrwola, chose the term Murngin for all Yolngu clans, Dhuwa and Yirritja, because it meant “Peoples of the Iron Age.” He drew on those special qualities of Birrinydji and the pre-Macassan period—namely iron-making technology and the belief in a high god—to separate the Yolngu block of clans from their Aboriginal neighbours. As Burrumarra would say, “We are Murrnginy. We believe in god” (McIntosh, 1994).

In distancing themselves from surrounding ‘stone-age’ peoples, Yolngu were displaying their strong sense of pride in their pre-Macassan past and in the power of their own land to deliver the benefits of civilization. They would not be lumped into the category of the primitive.

Burrumarra’s mentor, Harry Makarrwola, chose the term Murngin for all Yolngu clans, Dhuwa and Yirritja, because it meant “Peoples of the Iron Age.” He drew on those special qualities of Birrinydji and the pre-Macassan period—namely iron-making technology and the belief in a high god—to separate the Yolngu block of clans from their Aboriginal neighbours. As Burrumarra would say, “We are Murrnginy. We believe in god” (McIntosh, 1994).

In distancing themselves from surrounding ‘stone-age’ peoples, Yolngu were displaying their strong sense of pride in their pre-Macassan past and in the power of their own land to deliver the benefits of civilization. They would not be lumped into the category of the primitive.

Summation

The study of Yolngu oral history, so rich in mesmerizing detail, is unfortunately still in its infancy. The degrading of oral accounts to the realm of fantasy has resulted in much of that past becoming lost. However, Burrumarra was ever optimistic. Even though various Yolngu languages and their vital stories had been “buried” or “sent to the ground” in the past two hundred years, he said that “We can get them back.” Australian history does not begin in 1788 with British colonization. Rather, it begins with the oral historical accounts of the first peoples, and they are a vital resource for us all to cherish.

References

Macknight, C.C. 1976. The Voyage to Marege, Melbourne University Press, Carlton.

McIntosh, I.S. et al. 2020. Uncovering North Australia’s Pre-Macassan Visitor History https://www.pastmasters.net/early-contact-north-australia.html

McIntosh, I.S. 2015. Between Two Worlds. Essays in Honour of the Visionary Aboriginal Elder David Burrumarra M.B.E. Dog Ear Publishing, Indianapolis.

McIntosh, I.S. 1994. The Whale and the Cross. Northern Territory Historical Society, Darwin.

McIntosh, I.S. et al. 2020. Uncovering North Australia’s Pre-Macassan Visitor History https://www.pastmasters.net/early-contact-north-australia.html

McIntosh, I.S. 2015. Between Two Worlds. Essays in Honour of the Visionary Aboriginal Elder David Burrumarra M.B.E. Dog Ear Publishing, Indianapolis.

McIntosh, I.S. 1994. The Whale and the Cross. Northern Territory Historical Society, Darwin.

Table of Figures

Fig. 1. Google Earth enhanced map – MBOwen

Fig. 2. Wessel Islands rock art - MBOwen image

Fig. 3. David Burrumarra MBE & Dr. Ian McIntosh – IMcIntosh image

Fig. 4. David Burrumarra - IMcIntosh image

Fig. 5. Proposed Kora Kora D'Stretch rock art - MBOwen image

Fig. 6. Map of the Celebes – Macassar {current Sulawesi} – Bellin 1752

Fig. 7. A prau off Port Essington by Capt. Owen Stanley SLNSW

Fig. 8. David Burrumarra and the reconciliation flag.

Fig. 9. Cape Wilberforce - MBOwen image

Fig. 10. Macassans processing trepang - Mathaman Marika - Yirrkala 1964.

Fig. 11. Wessel Is. D'Stretch ~ rock art rendition of Banda Is. – MBOwen image

Fig. 12. Sultans of Tallo Graves- IMcIntosh image

Fig. 13. Entrance to Port Bradshaw - MBOwen image

Fig. 14. Google Earth enhanced map – MBOwen

Fig. 15 Birrinydji – detail of Reconciliation Flag - IMcIntosh image

Header image – Wessel Islands rock art - MBOwen image

Footer image – Macassan trepang processing site at Raffles Bay 1839 by Louis Le Breton

Fig. 2. Wessel Islands rock art - MBOwen image

Fig. 3. David Burrumarra MBE & Dr. Ian McIntosh – IMcIntosh image

Fig. 4. David Burrumarra - IMcIntosh image

Fig. 5. Proposed Kora Kora D'Stretch rock art - MBOwen image

Fig. 6. Map of the Celebes – Macassar {current Sulawesi} – Bellin 1752

Fig. 7. A prau off Port Essington by Capt. Owen Stanley SLNSW

Fig. 8. David Burrumarra and the reconciliation flag.

Fig. 9. Cape Wilberforce - MBOwen image

Fig. 10. Macassans processing trepang - Mathaman Marika - Yirrkala 1964.

Fig. 11. Wessel Is. D'Stretch ~ rock art rendition of Banda Is. – MBOwen image

Fig. 12. Sultans of Tallo Graves- IMcIntosh image

Fig. 13. Entrance to Port Bradshaw - MBOwen image

Fig. 14. Google Earth enhanced map – MBOwen

Fig. 15 Birrinydji – detail of Reconciliation Flag - IMcIntosh image

Header image – Wessel Islands rock art - MBOwen image

Footer image – Macassan trepang processing site at Raffles Bay 1839 by Louis Le Breton

Biographical Notes

Anthropologist Ian McIntosh is the Director of International Partnerships at Indiana University’s Indianapolis campus. He is an adjunct professor in the School of Liberal Arts (Anthropology and Religious Studies) and the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. Ian is a co-founder of the PastMasters, a heritage and history collective dedicated to investigating Australia’s links to the outside world in the days prior to European expansion in the East Indies and New Holland.

Ian McIntosh - [email protected]

Download paper

| arnhemlands_lost_past.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1519 kb |

| File Type: | |

Media Coverage

ABC media coverage coincided with 3 Humpback whales in the East Alligator River - the ABC News feed alone took 60,000 hits.

END